The changing face of the Rajinikanth cult

Many celebrities have fan followings worldwide, but few test the limits of fandom like Rajinikanth's

AirAsia routed special flights to Chennai when Rajinikanth’s Kabali released there this July. The planes were painted with the film’s poster

AirAsia routed special flights to Chennai when Rajinikanth’s Kabali released there this July. The planes were painted with the film’s poster

Image: AirAsia

G Mani, who heads a Rajinikanth fan club in Chennai, actually pawned his wife’s jewellery to pay for the iconic Tamil film star’s local birthday celebrations. In another instance, his fan club had cheerfully destroyed a cinema hall when the projectionist didn’t replay a popular song during a screening of Rajinikanth’s Padayappa on request. You meet many such obsessive ‘Superstar Rajinikanth’ fans in Rinku Kalsy’s documentary For the Love of a Man, which showed at the Venice Film Festival last year. The mega star has an estimated 150,000 Indian fan clubs, and is worshipped as a god mainly by thousands of fans throughout South India, in Mumbai and elsewhere. Many celebrities, and especially film stars, have fan followings worldwide, but few test the limits of the celebrity cult and fandom like Rajinikanth’s fans.

You simply cannot imagine the fan clubs of the top film stars worldwide—Tom Cruise, Olivier Martinez, Tony Leung or Min-sik Choi—let alone Bollywood’s Khans—threatening theatre managers and demanding block-booking of tickets for the prestigious first-day-first-show, resulting in shows at 3 am or 6 am. Your garden varieties of film stars have shows beginning at noon or 3 pm. In Tamil Nadu, many corporates declared the July premiere of Rajinikanth’s Kabali a holiday, and block-booked tickets for their staff; AirAsia even routed special flights to Chennai, the entire plane painted with the Kabali poster.

Images: Getty Images

I recently attended the first-day-first-show of Kabali at 6 am at Aurora, a single screener in Matunga, Mumbai. No Khan would get me out of bed at 4.30 am for a movie. Temple musicians were out in full form, playing the kombu (a curved trumpet) and chenda (drums) at the premiere. Members of the Maharashtra State Head Rajinikanth Fans’ Welfare Association and the Dharavi fans’ Tanka Nilavuhas (‘Golden Moon’ in Tamil) danced hysterically, bound by a trance-like devotion, brotherhood and self-fulfilment. It was as if, with Rajinikanth around, even a nobody became a somebody. A lookalike from Pune turned up, wearing a Kabali-style suit and shades (“cooling glasses”, the Tamilians call them). Fans also organised a free eye camp and blood donation drive at the premiere, right inside the theatre.

Traditionally, the film print would be carried ceremonially to the theatre, following a puja in a nearby temple, with a pal abhishekam (ritual bathing in milk) of a giant, 50-foot cut-out of the star at Aurora. Earlier, going to a Rajini movie was like getting married in the dark: Every time there was great dialogue-baazi, you were showered with flowers strewn by fans in the back rows. Lore has it that a fan, trying to save Rajinikanth from the villain in a movie, once hurled a knife at the villain, nicking the screen.

Image: Getty Images

From what I understand, Beatlemania, by contrast, was mainly to do with fans jamming their concerts, screaming their lungs out, trophy-hunting, busting police cordons and trailing them everywhere. American political activist and writer Barbara Ehrenreich described this ’60s phenomenon, especially of teenage girl fans letting go, as “the first and most dramatic uprising of the women’s sexual revolution”.

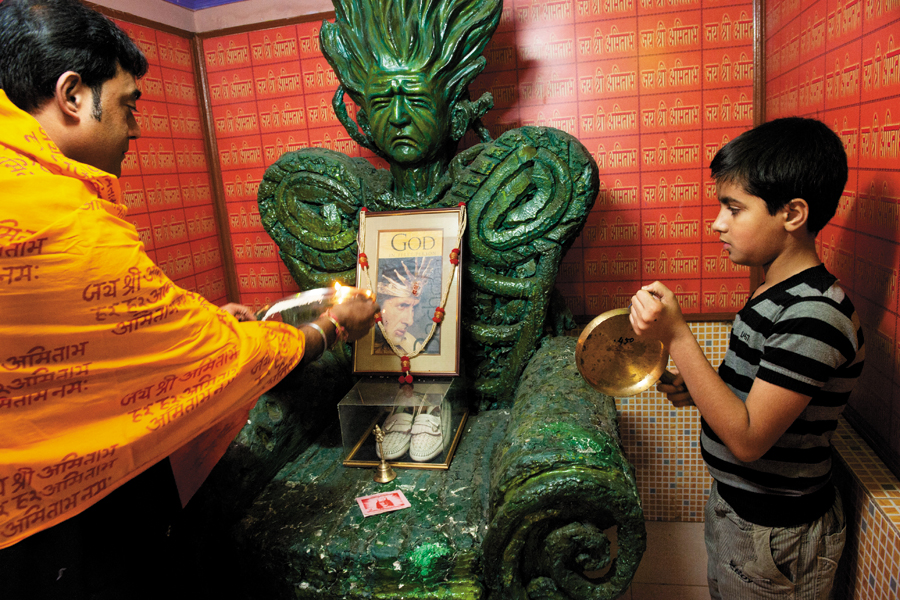

Back home, Bollywood star Amitabh Bachchan’s fans have found more original ways of expressing their devotion. There’s a temple to the star in Kolkata, where daily aartis are performed. When Bachchan suffered a near-fatal accident while shooting for Coolie in 1982, havans were conducted by fans nationwide, and one fan even ran backwards from Baroda (now Vadodara) to Mumbai barefoot, covering about 430 km to Bachchan’s residence, after he returned home from hospital.

Image: Sanjay Austa

Other film stars in South India also have high-voltage cults, including J Jayalalithaa (‘Amma’), actress-turned-politician, Tamil Nadu chief minister and AIADMK chief. Loyalists routinely prostrate before her on the floor. At least 16 people are believed to have committed suicide after Jayalalithaa was sentenced to a four-year jail term in a 2014 legal case, for amassing disproportionate assets worth Rs 66 crore, her indictment provoking outrage: Some set themselves ablaze, others hanged themselves, one jumped before a speeding bus, and 10 died of a heart attack on hearing the news.

Most of these cults project the film star as divinity. There is, of course, a historic political-film connection in South India, as film stars, including Sivaji Ganesan, MG Ramachandran (MGR), Jayalalithaa and NT Rama Rao (NTR) have played gods and good guys on screen, and later parlayed their fans’ goodwill into votes at election time.

Image: Babu Babu / Reuters

Tamil Nadu has seven film stars-turned-politicians. While the state’s politicians compete to dispense cheap booze, subsidised meals, free electricity and free “mixies” (grinders), deeply entrenched fan clubs jostle to distribute free lunches, organise blood donation and tree plantation drives, and generally imitate Rajinikanth, whose title in Sivaji The Boss (2007) is explained as bachelor of social service.

Having attended the first-day-first-show of Rajinikanth’s Kochadaiiyaan (2014) and Kabali at Aurora, I notice the audience profile changing, as Rajinikanth moves up from being a Tamil film star to a more universal one. Earlier, it was almost entirely loyal Tamil fans from Dharavi and Chembur. Now the audience is more cosmopolitan, including office-goers in pinstripes and hordes of mass media students eagerly studying the phenomenon.

So sadly, the lunacy inside the theatre is dialled down. And, blasphemy of blasphemies, the premiere swarmed with a number of blue-lit mobile phone screens during the screening, as many in the audience, mostly yuppy cosmopolitans, tweeted and Facebooked in real time, about being at the first-day-first-show of Kabali. It’s the price of Rajinikanth trending.

Meenakshi Shedde is South Asia Consultant to the Berlin Film Festival, award-winning critic, curator to festivals worldwide and journalist. Her email is meenakshishedde@gmail.com

(This story appears in the Sep-Oct 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)