Exclusive: How Sequoia became India's biggest venture capital firm

Sequoia Capital India Advisors has written cheques of all sizes—from seed to growth—and never lost sight of an exciting startup. But liquidity and exit concerns remain

(From left) Sequoia’s GV Ravishankar, Mohit Bhatnagar, Shailesh Lakhani, Abheek Anand and Shailendra Singh want to find bold founders, who want to “put a ding in the universe”

(From left) Sequoia’s GV Ravishankar, Mohit Bhatnagar, Shailesh Lakhani, Abheek Anand and Shailendra Singh want to find bold founders, who want to “put a ding in the universe”Image: Mexy Xavier

“We don’t think of ourselves as wanting to just become a founder’s best friend,” says Ravishankar, managing director at Sequoia India, the country’s largest venture capital firm with approximately $4.5 billion in assets under management across seven funds.

“We have a lot of empathy for the founders. But, we have a fiduciary responsibility to our clients (limited partners or LPs) as much as we do to our founders. We want to be their best business partner, their first port of call. We wear that badge with pride. Our role is to make sure that they deliver to their best potential, not necessarily be their best friend,” Ravishankar lets on.

It’s a loaded statement that can stir up extreme emotions in the tech universe, a melting pot of brilliant minds, chronic insecurities and colossal egos. After all, friends are altruists. Business partners? Perhaps self-serving. At the end of the day, they have a shop to run.

At Sequoia India, they aren’t swayed by such emotions. “Let’s do what’s right for the founder and the company” and “serving ourselves by serving others” are the recurrent themes. Here, they like their conversations upfront. Fawning isn’t their forte.

“One thing about Sequoia which is under-appreciated in the outside world is the culture,” says Abheek Anand, managing director at the firm.

Amrish Rau knows a thing or two about this. Rau’s tryst with Sequoia began in 2012, when he teamed up with Jitendra Gupta to start Citrus Payment. Back then, Sequoia had stunned Rau by deftly writing a $1.8 million cheque for a 24 percent stake, while the expectation was to merely match another offer of a million dollars for the same stake.

Cut to 2015, Rau and Gupta were in a fix. The merchant payments business was growing at a fast clip, but the duo also harboured ambitions to make a dent in consumer payments. Despite sinking $3-4 million, Citrus could barely find a footing in an overcrowded market. To make matters worse, the founders couldn’t agree on whether to stay put or move on.

Rau and Gupta sought Bhatnagar’s counsel. Scrap it, he said. “This time, it wasn’t a soft and nice kind of an answer. He was pretty blunt,” recalls Bhatnagar. “Founders don’t always want somebody to be blindly following our cue. We also need honest external counsel. It helps.”

Jaydeep Barman of Rebel Foods, which started out by selling wraps under the Faasos brand, will agree. In 2016, the company was struggling to push its average order value beyond ₹200 and it was evident that selling only wraps wouldn’t suffice. Barman promptly launched pizzas, but they barely sold.

At a subsequent board meeting, Barman got a crisp repartee from Ravishankar, “I don’t think that I will buy a pizza from Starbucks.” Thus, it dawned upon him that consumers associate brands with certain products, and Faasos certainly wasn’t a pizza brand that they looked forward to. “That was the genesis of our multi-brand strategy.”

Rebel Foods has since snowballed into a ₹550-crore revenue run rate company, on the verge of snaring at least $100 million in fresh funds. Sequoia’s estimated $40-50 million investment in the company is likely to swell approximately five times. As for Citrus, PayU bought the company for $130 million in an all-cash deal, making a windfall for the founders, the firm’s employees and of course, Sequoia.

Both Citrus and Rebel Foods are early investments by Sequoia. So are Druva, Pine Labs, Oyo, Zilingo and Go-Jek, where Sequoia is estimated to have clocked between $250 million and $1 billion in notional gain at the firms’ current valuation.

At Sequoia India, they like to back nifty companies just about the time they start to take wing. This is a page borrowed from a playbook written about 47 years ago by the firm’s legendary founder Don Valentine—that Sequoia will invest in early stage companies that will use technology to transform industries and become a preferred business partner to founders for at least five to 10 years and beyond.

Sequoia’s LPs aide this vision. “More than 80 percent of Sequoia’s LPs are non-profits—universities, endowments, charities, foundations, etc. We keep it like that by choice,” says Shailendra Singh, managing director at the firm. “Our LP base is perpetual in nature, which gives us a long-term orientation in our thinking and you can see that in our consistent investment approach in India.”

Druva and Pine Labs, where Sequoia invested about a decade ago, are telling tales.

In a world where Swiggy and Udaan sprinted past the billion-dollar valuation milestone in three years since inception, Druva became a unicorn this year. Pine Labs is gunning for $1.5-2 billion in valuation for its latest fundraise. According to people in the know, Sequoia’s stake in the company will be worth close to $1 billion post Pine Labs’ latest fundraise, almost as much as what Accel Partners pocketed from Flipkart.

Says Singh, who had made five futile attempts to get an audience with Sequoia US investors while running Java Media in the early 2000s, “Our mindset is the same as what we see in our most successful founders, which is to keep a steady ship, focus on the long term and persevere.”

*****

Sequoia India has one of the largest investment teams among local VC firms. In the picture are six principals at the firm—(seated, from left to right) Sakshi Chopra, Tejeshwi Sharma, Anjana Sasidharan and Ashish Agrawal; (standing, from left to right) Harshjit Sethi and Ishaan Mittal. The seventh principal, Pieter Kemps, is based in Singapore

Sequoia India has one of the largest investment teams among local VC firms. In the picture are six principals at the firm—(seated, from left to right) Sakshi Chopra, Tejeshwi Sharma, Anjana Sasidharan and Ashish Agrawal; (standing, from left to right) Harshjit Sethi and Ishaan Mittal. The seventh principal, Pieter Kemps, is based in SingaporeImage: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

For five years after opening for business in India in 2006 through a partnership with WestBridge Capital, Sequoia India did everything its counterparts in the US and China didn’t. Seed investments like Scio Health Analytics and Pine Labs were far and few as Sequoia usually dabbled in public markets and backed pharma, infrastructure and manufacturing companies.

Essentially it was becoming a private equity firm in spirit, while in the US and China, peers were known to discover hidden gems in ratty coffee shops and scruffy garages. Like Apple, Google, LinkedIn, Paypal, YouTube, WhatsApp and Airbnb in the US. Like Didi Chuxing, Meituan Dianping and Bytedance in China.

In February 2011, the top brass—Sumit Chadha, KP Balaraj, Sandeep Singhal and SK Jain—quit to relaunch the WestBridge brand. The current leadership stayed back to embrace the Sequoia way of life—find bold founders, who, like Apple’s Steve Jobs, want to “put a ding in the universe”.

There was another element to Sequoia’s investment philosophy. The firm favoured frugality and capital efficiency. Mega burn models were a strict no-go. This wasn’t any different from what they did in the US. For instance, Sequoia isn’t an investor in Amazon.

Similarly, for a long time, Sequoia India treaded the alluring-yet-slippery consumer internet terrain with caution—some of the firm’s capital guzzling, but highly rewarding investments like Zomato and Oyo started out on a different note; Zomato as a restaurant information and review platform that survived on advertisement revenue and Oyo as an aggregator of budget hotels.

The firm passed on companies like Flipkart and FirstCry and didn’t invest beyond $5 million in a single round in Ola. But it couldn’t afford to remain a silent spectator, predominantly backing software and financial services companies, as the consumer internet wave swept Indian shores circa 2014-15. Sequoia also threw its hat in the ring. The firm invested in food delivery startup TinyOwl, hyperlocal delivery startups Grofers and PepperTap, logistics firm Runnr and fashion startups Voonik and Craftsvilla. Barring Grofers, which staged a comeback after a wobbly start, the rest found the going tough.

It was a lesson learnt. “In consumer internet deals, there can be a high mortality rate, but you can have a very big win. You have to have the stomach to go through a tonne of volatility,” says Singh. “Candidly, we did a little less investment in areas that had a poor economic profile earlier. But, we saw global investors putting in billions of dollars into these companies with high burn and the market evolved a lot. So we changed our strategy to back more consumer internet companies, but also remained disciplined to do most of it very early stage so that the wins can easily pay for the losses.”

Sequoia has since made a spate of early stage consumer internet investments, Cred, Mobile Premier League, BharatPe, Meesho, Bounce and Stanza Living to name a few.

Says Shailesh Lakhani, managing director at the firm, “Many of those 1.0 companies had difficult economics. We believe there will be a next generation of companies in all those areas and it reflects in many of our more recent investments, for instance Bounce and QuickRide in mobility and Meesho in commerce. We believe they have powerful models, fundamentally strong economics and massive mass market use cases.”

At a time when it appeared that the house was in order, Sequoia India was again jolted, let’s say, for being Sequoia. Between late 2017 and early 2018, three senior executives, Gautam Mago, Abhay Pandey and VT Bharadwaj, who didn’t agree with the firm’s inclination towards early stage and technology deals, decided to part ways. They had backed money-spinners like Oyo, Indigo Paints, Prataap Snacks and Vini Cosmetics.

Sequoia has since realigned its India business into early stage and growth teams, led by Bhatnagar and Ravishankar respectively.

“Those of us who continue to work at Sequoia are aligned on two things. One, massive focus on early stage investing. Second, our experience shows that investments in technology and technology-enabled companies produce the best venture returns. The early stage and tech focus is Sequoia’s DNA,” says Bhatnagar. “It is easy for us to say no to a bunch of stuff now. It is okay to part ways with others who don’t believe in this, because the ones who remain are wedded to this focus.”

*****

At Sequoia India, they don’t always get it right. The firm passed on logistics startup Delhivery at the seed stage. The business relied heavily on ecommerce, they thought. Delhivery is currently valued at $1.6 billion and counts SoftBank as an investor. Freight transport startup Rivigo, now valued at about $900 million, didn’t pass the muster because the sector wasn’t appealing. Freshworks didn’t make it because some of its global peers, like Zendesk, weren’t creating ripples. Between 2011 and 2015, Sequoia also said no to many financial services companies fearing regulatory hurdles.

The firm has made amends, but course correction was expensive. Sequoia invested in Rivigo’s competitor, Blackbuck, reportedly at a valuation of about $950 million. It wrote a cheque to Freshdesk at a $650 million valuation. Five Star Finance and Finnova are some of their recent financial services investments.

When the India leadership went into a huddle to identify what led to some of these expensive misses, all fingers pointed towards overanalysing.

“Sometimes, it isn’t good to be too analytical in the early stages, especially while trying to forecast market size,” says Bhatnagar. “One of our mistakes in the past has been underestimating the future market size without taking into account that companies can be so disruptive that they can create and expand markets. The rear view mirror can’t be an accurate indicator of the future.”

Shah didn’t respond to Singh’s first message on LinkedIn in January 2010. He remained evasive for months, until Singh and his team managed to track him down by calling his office phone. Singh wrote a seed cheque after their first meeting in 2011 and continued backing FreeCharge through the lean patches until Snapdeal bought FreeCharge for a whopping $400-450 million in 2015.

Says Shah, who joined Sequoia after the FreeCharge sale, only to quit a year later to launch Cred, which also counts Sequoia as an investor, “Not even once did I have a long discussion or negotiation with Shailendra on fundraise. He always said, ‘let’s do whatever is right for the company’.”

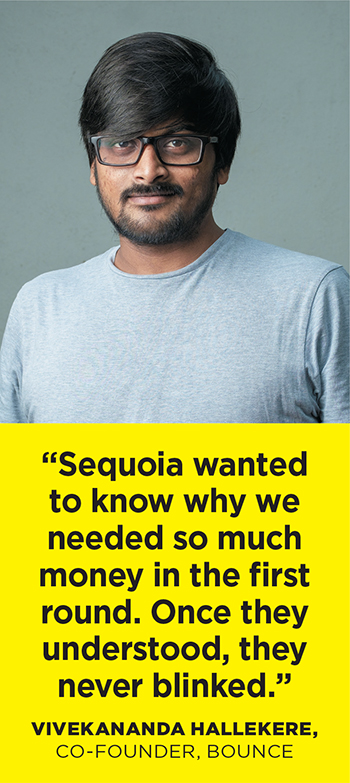

FreeCharge isn’t an exception. Vivekananda Hallekere, co-founder and chief executive at Bounce, says Sequoia isn’t one of those stingy operators. Sequoia pitched in with $4.5 million in a $9 million funding round, when Bounce had exactly one dockless scooter to show for all its worth. “We never had those $1 million for 20 percent kind of conversations with Sequoia. They wanted to know why we needed so much money in the first round. They went behind ‘why’ and once they understood, they never blinked,” says Hallekere.

Bounce is also an example of Sequoia never losing sight of a seemingly exciting company, even if it does not invest immediately. The firm kept in touch with Hallekere and team for about two years before investing. Sequoia’s recruitment team was helping Hallekere strengthen the company’s top deck long before the firm issued a term sheet. “It was the first time that I had that kind of a conversation in my life, brainstorming with their recruitment head for potential hires. It felt nice. And we were still four to five months from the deal to happen,” says Hallekere.

Doing business with Sequoia is hassle-free. Notes are exchanged on WhatsApp. Disagreements don’t snowball into ego battles. Enforcing sweeping changes in a company isn’t Sequoia’s style, says Lokvir Kapoor, executive chairman at Pine Labs.

“They help an entrepreneur develop the confidence to aim high. I reached out to Shailendra at a difficult moment when we were presented a challenge by a large multi-national… he told me with a smile, ‘No worries, it’s our job to back the Davids against Goliaths’,” he adds.

Also, Sequoia goes much beyond its fat purse. They call themselves “active capital”. Sequoia India’s support team of 25-odd people handholds founders with everything from recruitment to business development and market intelligence.

There is also an opportunity to mingle with Sequoia’s global leaders and portfolio founders, interactions that can be extremely fruitful and pivotal. Rebel Foods’ Barman would have continued paying exorbitant rents for high street stores instead of migrating to cloud kitchens, had he not heard the legendary Doug Leone say at a gathering of Sequoia portfolio founders that a CEO’s biggest job is to remove friction from businesses.

Similarly, Rau and Gupta of Citrus Payments would not have launched LazyPay, a consumer credit product, had they not met Roelof Botha, an investor at Sequoia US and former chief financial officer at PayPal, who dwelled at length on the importance of a credit business for fintechs and how Square, a fintech firm founded by Twitter’s Jack Dorsey, would end up becoming a huge winner. “I even ended up buying Square shares,” says Rao with a chuckle.

Sequoia India has always motivated founders to break the mould. On several occasions, the firm led by example.

Sequoia India was the first Indian fund to scope out foreign shores. In 2013, the firm wrote in its presentation to potential LPs for its fourth fund that it will begin to invest in Southeast Asia. The firm intends to deploy 20-30 percent of its corpus in Southeast Asia, where it has scored some big hits in Go-Jek, Carousell, ONE Championship, Zilingo and Tokopedia. This apart, Sequoia India has stakes in Australia’s HealthEngine and Bangladesh’s ShowUp and Stockholm-headquartered Truecaller. According to industry executives, the India units of Accel and Lightspeed have recently started scouting deals in Southeast Asia.

Sequoia has also taken its pursuit of early stage companies a notch higher with the launch of Surge, an accelerator programme that would take in 30-40 startups annually for four months and invest $1-2 million in each company. The firm has hired Rajan Anandan, former vice president, India and Southeast Asia at Google, to head Surge. Recently, Sequoia raised a $200 million fund for seed investments.

In effect, Sequoia India is the only Indian venture capital firm that has put a structure in place to write cheques of all sizes—from seed to growth.

Not everyone is euphoric about Sequoia though. Printo’s Manish Sharma once claimed that Sequoia held back promised tranches and offered to subsequently invest at a lower valuation; Housing’s Rahul Yadav chided Sequoia for trying to poach executives at his startup; Flipkart’s Sachin Bansal once tweeted that he was lucky to not have Sequoia as an investor in Flipkart.

Says Rajul Garg, managing partner at venture capital firm Leo Capital, whose association with Sequoia goes back to the early 2000s, when Garg co-founded GlobalLogic, “They try to do what’s right for the founder. This is hard to do as some companies go through trials and tribulations, but by and large, when push comes to shove, they are founder-friendly because they are in it for the long term.”

In fact, Sequoia backed Tapzo through multiple pivots and failings and kept the company afloat until it found a home in Amazon. Similarly, it invested in Sai Srinivas Kiran and Shubham Malhotra’s second startup, Mobile Premier League. Their maiden venture Creo, where Sequoia was an investor, didn’t scale and was sold to Hike Messenger.

Adverse opinions are minor niggles. Sequoia has bigger concerns to address. Like liquidity. While a mammoth fund gives Sequoia the luxury to lead at least two consecutive funding rounds in promising companies and maintain a substantial stake, the sheer size of the fund also makes the task of scoring high multiples equally daunting.

There have been profitable exits, Scio Health Analytics, Just Dial, Quick Heal, Citrus Payment and Equitas, to name a few. In a $180-million deal with Madison Capital, Sequoia either partially sold its stake or completely exited some of its portfolio companies, including Micromax. More recently, the firm sold a small part of its stake in Byju’s for about $180 million and in Pine Labs for $150 million.

Sequoia could clock another bumper return in Oyo in the months to come. Oyo’s Ritesh Agarwal is reportedly contemplating a share buyback from some of the early investors to bulk up his holding in the company and buy out early investors such as Sequoia and Lightspeed. According to Tracxn, Sequoia has so far invested about ₹165 crore in the company for a 10.5 percent stake that is worth ₹3,250 crore.

“Exits are certainly a concern, not just for Sequoia but every other investor. As compared to others, Sequoia has the largest corpus in India, so they could feel more pressure. But, they are sitting on some very good assets which are well placed to give them strong outcomes and they have already realised some liquidity in the recent past,” says Vinod Murali, managing partner at Alteria Capital.

Ravishankar calls the stake sale “self-imposed discipline” and brushes aside suggestions that the firm is under duress. Sequoia has time. It will make money by being a good student of the business. Says Ravishankar, “In our business, few things really work to become very large, everything else ends up being a learning. So there is a lot to learn from.”

(This story appears in the 02 August, 2019 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment