Bangalore's Rain-Catcher: The man who never paid for water

He put his beliefs into practice and tested the rain harvesting concept in his house 19 years ago

How to get ROI from your house by going green

Monsoon rains in Bangalore may help raise water levels in dams that supply water to the city. But there is one man in the city who is unhappy.

“We should learn to keep the rains in our homes,” says A.R. Shivakumar, senior fellow and principal investigator- RWH, Karnataka State Council for Science and Technology, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

Shivakumar has his reasons. With Hesaraghatta lake, a manmade reservoir, and Tippegondahanally reservoir drying up, Bangalore’s entire population(urban and rural) has to depend on the Cauvery waters. Karnataka can draw only 682.5 million litres a day of Cauvery waters which it shares with Tamil Nadu. But the requirement for just Bangalore (urban and rural) is 1,400 million litres per day or 18 thousand million cubic feet (TMC).

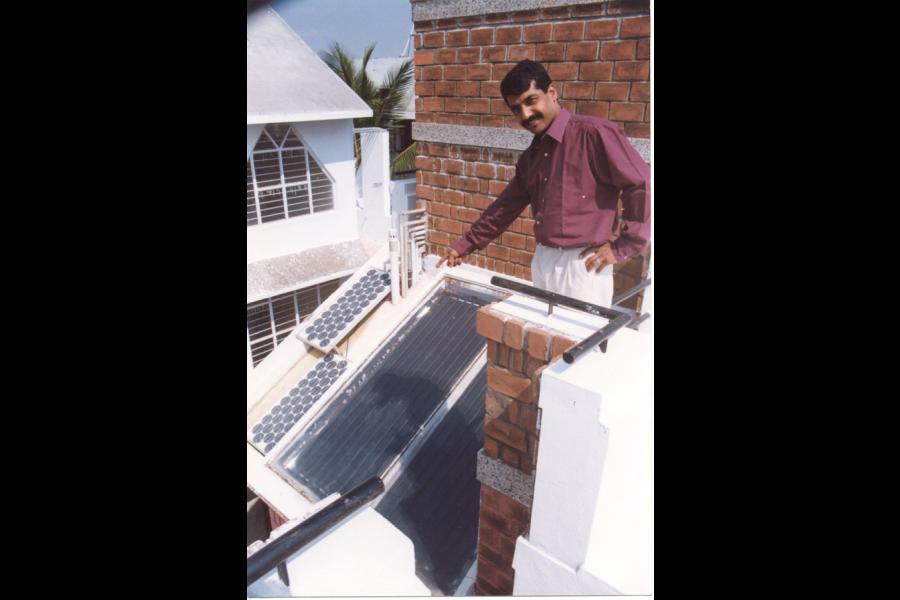

“To meet this 18 TMC limit, rain water harvesting is the answer,” says Shivakumar. He put his beliefs into practice and tested the concept in his house 19 years ago. “Shivakumar believes your house should give you a return on your investment,” his wife, Suma Shivakumar says. “He managed to build this house for Rs 400 per square feet when the norm was Rs 600 per square feet in 1994,” she says.

Shivakumar has not had to pay a single penny to the corporation for water in the past 19 years.

“First, we listed the requirements for a house: energy, good comfort living, air, water,” he says. “We found to our surprise that the answer is with nature and not with the KEB (Karnataka Electricity Board), BWSSB (Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board), etc.,” he says.

He sat and mapped the water consumption by an average family by analyzing the water bills of residents in the locality. He found that it matched WHO norms -- a family for four would use approximately 500 litres of water per day, which resulted in 1.825 lakh litres of water consumed every year.

After analyzing the water bills, Shivakumar dissected the rainfall data of his 40X60 plot for the past 100 years. “To my surprise, I found we were getting 2-2.5 lakh litres consistently in the last 100 years,” he says. The plot got 2 lakh litres even in the worst year of rainfall. There is one catch: It rains 60-70 days in a year but the water should last for 365 days. Shivakumar found that the longest gap between two good rains was 90-100 days. “Within three months, there’s a good rain in Bangalore,” he says, “And if you take the daily consumption of a family, it is almost 400 litres of water per day and multiplied by 100, you need storage of 40,000 litres to meet the times when there is no rain.”

Rain water harvesting has almost come to mean ground water recharge for most Bangaloreans, where they send the rain water to the ground, but for Shivakumar it is just the beginning.

First, he built a roof tank with a 5,000 litre capacity. On the ground floor, he built another 5,000 litre capcity tank, which catches most of the rain water – no other tank catches rain water as this tank. On his portico, he built the biggest tank of 25,000 litre capacity, and then building his garage two-and-a-half feet above ground level, he built another 10,000 litre tank.

Each tank has a pop-up filter, which Shivakumar has a patent for. It is marketed as the Rain Tap Pop-up filter in Gujarat. This filter removes all the mud, muck and other particles from rain water. The overflow from the tank goes to the portico tank, which ultimately sends it to the garage tank. The garage tank is the only tank that uses electricity to pump water to the roof tank.

The entire house runs on the ground floor tank, which has a capacity of 5,000 litres, whereas the portico and garage tanks serve as storage tanks for water when there is a gap in rainfall. He also ensures appliances like washing machine reuse waste water.

Shivakumar has trained several architects and contractors to integrate such water systems in new constructions. In peak summer, at least five to seven tankers ply every hour in upcoming suburbs like Ramamurthy Nagar.

A water tank usually sells 4,000 litres for Rs 300-500, but when there is a shortage, the price goes up as high as Rs 900-1,600. Shivakumar estimates that there are about 13.5 lakh houses similar to his in Bangalore. If even half of them were retrofitted with water storage systems (it can cost about Rs 30000-50000 per house), Bangalore may never face a water shortage. And what goes for Bangalore goes for other cities in India as well.

The thoughts and opinions shared here are of the author.

Check out our end of season subscription discounts with a Moneycontrol pro subscription absolutely free. Use code EOSO2021. Click here for details.

-

foad

foadi need this genius\' information on how i can follow his example for my bungalow in Bangalore

on Nov 19, 2019