Welcome to history: How royal dwellings turn into luxury hotels

Transforming storied heritage residences into luxury hotels is all about striking a balance between conservation and commercial requirements

In properties like the Umaid Bhawan Palace in Jodhpur, the royal family stays on the premises. Restoration artists work closely with them while redoing the estate

Image: Taj Hotels Palaces Resorts Safaris

In the Ahilya Fort’s 17-year life as a hotel, Richard Holkar remembers one single guest who took a look around to check the facilities, got back into his car and drove off.

“We are expensive, but we aren’t a typical five-star hotel you see,” says Holkar, pithily summarising the emerging category of heritage hotels, of which the Ahilya Fort in Maheshwar, Madhya Pradesh, is one. “We don’t have TV, we don’t have room service,” he adds. The 73-year-old Beatles fan is the son of Yeshwant Rao II, the last maharaja of Indore, and one of the descendants of Ahilya Bai, the Maratha queen who ruled the region in the 18th century and after whom the palace on the banks of the Narmada is named.

In 1971, Holkar and his ex-wife Sally came back to India from the US, took over the derelict Ahilya Wada, restored it and opened it as a heritage hotel in 2000. What started with four rooms back then is now an elegant property with 14 rooms in six different areas, “so that you don’t really feel that you are living in a hotel”.  The Ahilya Fort in Maheshwar, Madhya Pradesh, opened as a heritage hotel in 2000. It now has 14 rooms, but no TV or room service

The Ahilya Fort in Maheshwar, Madhya Pradesh, opened as a heritage hotel in 2000. It now has 14 rooms, but no TV or room service

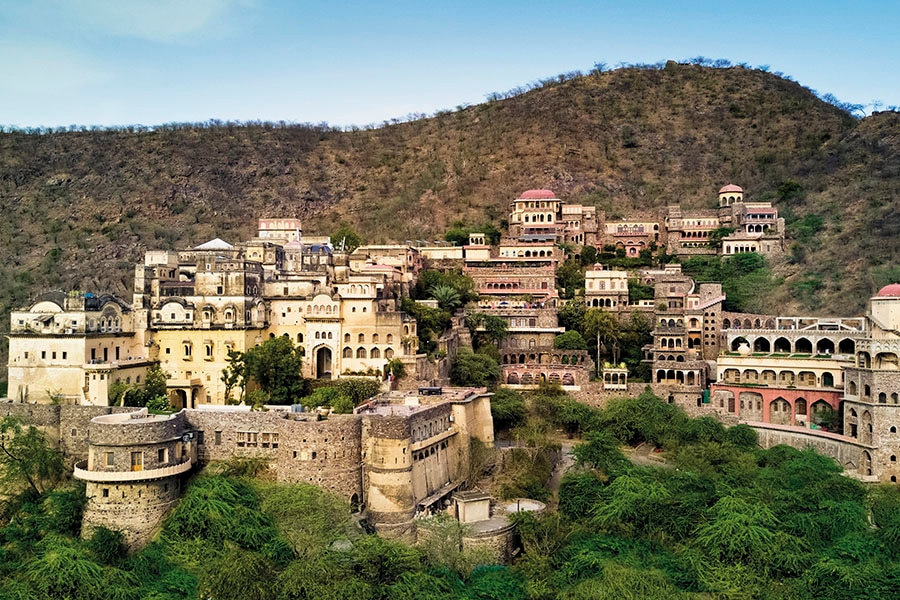

Image: Ahilya FortAhilya Fort’s transformative journey from a palace to a not-exactly-a-hotel hotel isn’t unique. In India, a number of residences of the erstwhile royalty and aristocracy have turned into heritage hotels to find commercially viable ways of preserving them. The growth of the sector can be measured from the fact that the Indian Heritage Hotels Association, which was formed in 1990 with 14 members from Rajasthan to revive the state’s rich cultural heritage, has expanded to 16 states by 2017, with 191 members. Says Aman Nath, founder and chairman of Neemrana Hotels and a conservation enthusiast himself, “If you tell someone in America that you want to experience life like it was in the 14th century, it sounds far-fetched. But in India, it’s easy here, the past and the present continue to live side by side.”

But turning a royal dwelling into a hotel isn’t a simple architectural transformation it mandates a sense of history and conservation to capture the unique essence of every property, not just its scale of opulence. Most of the royal families that either tie up with luxury chains or rope in architects to turn their homes into standalone hotels have a simple brief: Stick to the spirit and don’t fix anything that’s not broken. Attached bath and hot and cold running water is fine, but Nath, for instance, didn’t want to ruin the look and feel of the Neemrana Fort-Palace, a 15th century property belonging to the descendants of Prithviraj Chauhan III, by installing Italian marble and jacuzzis in the bathrooms. “Restoration is a creative challenge and should be done intuitively it should not be overpowering,” he says.

“I don’t want to build anything new,” Holkar, too, had told conservation architect Ravi Gundu Rao while handing over the Ahilya Fort. Among the necessary structural changes was the rot that termites and water had caused to the interlocking wooden members, weakening the pillar and beam construction. It caused the first floor to shift up by 12 inches and the front of the building, including the drive-in, went belly up by about 20 cm. So, in some places, the architects replaced the wooden members with steel and clad them with old wood. While that retained the aged look, it also brought down the exorbitant costs of replacing teak logs. Besides, the interlocking quadrangles with courtyards in the middle, typical of Marathwada architecture, were tweaked—walls pulled down and put up at different places—to reorganise spaces to make them comfortable for guests. That apart, in close to two decades since it was thrown open to guests, there has been little visual change to the 18th century Maratha fort.  The restoration job of the Falaknuma Palace lasted almost a decade. Extreme care was taken to not damage any of the walls within the palace

The restoration job of the Falaknuma Palace lasted almost a decade. Extreme care was taken to not damage any of the walls within the palace

Image: Taj Hotels Palaces Resorts SafarisHospitality major Taj Hotels Palaces Resorts Safaris has in its stable many royal palaces that they’ve restored and turned into luxury, boutique hotels. “We don’t believe in manufacturing palaces. Instead, we find these hidden gems and restore them carefully,” says Chinmai Sharma, Taj’s chief revenue officer. “It helps us create a differentiated experience in a cluttered market, where a lot of luxury hotel chains provide a me-too experience.”

In a restoration job that lasted almost a decade (the hotel opened in 2010), the Group hired architects Rahul Mehrotra & Associates to carry out a conservation survey of the palace and the London-based integrated design firm WATG, led by chief architect Nick Poynton, to create an architectural design. Extreme care was taken to not damage any of the walls within the main palace. This proved to be a major challenge while installing the air conditioning system and upgrading the lights within the main palace. After a lot of debate on the ducting pattern, the experts decided to provide air conditioning only in certain areas, like the chess room, the 101-seater dining hall, the hookah room or the billiards room. At the historical suites, all the wiring has been routed through the floor to ensure that murals and paintings are not affected.

Among the grandest Baroque mansions in the country, the Falaknuma Palace’s interiors were done up with the finest materials and finishes, ranging from leather upholstery and velvet tapestry to the best marble and Burma teak, which had to be vetted by the tastes of Princess Esra. For instance, only the fourth or the fifth iteration of the leather work at the palace was approved and it took almost a year for the project to be completed.

“The royals are very attached to the residences, so we work closely with them. In some properties, like the Umaid Bhawan Palace in Jodhpur, the royal family of Maharaja Gaj Singh stays on the premises. The commonality between us is their passion for restoring their residences and our passion for sticking to their ethos while delivering great guest experiences,” says Sharma.

While the old wing of the Neemrana Fort-Palace, a 15th century property near Delhi, has been minimally tampered with, the conference wing with lifts flows out in the same idiom

Image: Pranshu DubeyLikewise, the Jehan Numa Palace in Bhopal has grown from 14 rooms, when it opened as a hotel in 1983, to a 100-room property that comprises banquet halls, swimming pools and spas. But even as requests for expansion poured in, and the hotel began to cater to a section of business travellers demanding amenities similar to other luxury hotels, it carried on the construction within the contours of General Khan’s combined architectural styles of colonial, Italian renaissance and classical Greek, and retained big courtyards and fountains, the signature styles of begums who ruled the state. “The architecture in those days wasn’t concrete and columns. The palace was constructed with bricks and limestone. We faced a lot of challenges in the initial stages of expansion, but now we’ve overcome those,” says Rashid.

But despite its exclusive and somewhat restrictive nature, heritage tourism is picking up in India. Both Holkar of Ahilya Fort and Nath of Neemrana Hotels peg the number of domestic bookings to more than 50 percent in the last season. The rise in Indian tourists can be attributed to a bouquet of unique experiences reminiscent of the royal era that the hotels offer. Jehan Numa is perhaps the only heritage hotel in India to keep thoroughbred horses on the property. “Before we got into the hotels business, the family was into breeding racehorses. While we have shut the stud farm, we continue to keep some of the horses and, every morning, while guests have their cup of tea, the horses are exercised around the property,” says Rashid.

“At Taj Falaknuma,” says Ritesh Sharma, general manager, “right from the arrival in the Nizam’s buggy painted in arabesques of gold to guests being showered with rose petals as they climb the white marble stairs at the entrance, the hotel offers a royal getaway to travellers. Guests can access the Nizam’s study table for writing on the palace’s impression book as well.” The hotel has a librarian to guide guests through the collection of rare books and manuscripts—that includes one of the most acclaimed collections of the Quran selected by the Nizam himself—in a library that is a replica of the one at Windsor Castle in England.

Living life king-size may be a cliche, but it may well be worth it.

First Published: Oct 01, 2017, 06:56

Subscribe Now