It was late February when Forbes India met Bhaskar Bhat, managing director of Titan Company, in Bangalore. This was only a month after the third quarter results of the last fiscal were declared. The expectation was that the 59-year-old would be preoccupied, even on edge. The numbers had been devastating for the company. Net sales were down to Rs 2,675 crore, a 12 percent dip over the same period last year.

The disappointment was exacerbated because the October-December period marks the festive season during which consumer spending peaks. Jewellery and watches are inevitably in demand these are product categories in which the company has a dominant brand positioning. But the double whammy of falling gold prices and weakening consumer sentiment had not spared even the mighty Titan, jointly owned by the Tata Group and the Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation.

It follows that Bhat should have been retooling strategy. Instead, he showed no intent of moving a single piece on his well thought-out chessboard. “Strategy is not based on the outcomes of a couple of quarters,” he pointed out. “Once sentiment improves in a year, we should be back to high growth.”

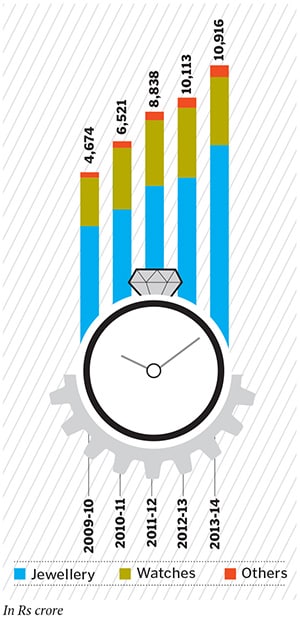

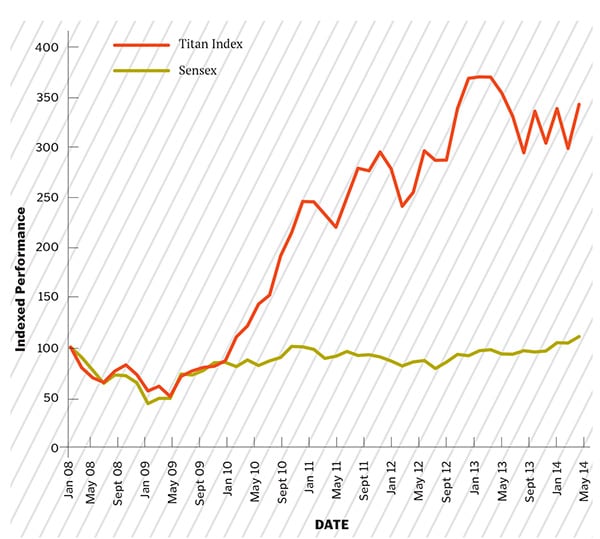

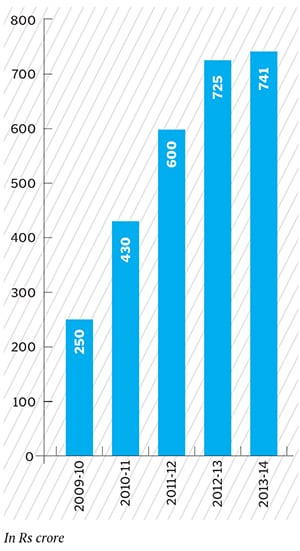

Fast forward to the quarter just gone by and Bhat’s optimism has been validated. There has been a marked improvement in consumer confidence resulting in increased footfalls at Titan’s stores. Even watches—something people buy less and less these days—grew by 12 percent. Overall sales for FY2014 ended 8 percent higher at Rs 10,916 crore and profits were up 2 percent to Rs 741 crore. Aided by a hopeful market, the stock, too, rallied 25 percent since May 6, when its annual results were declared, to Rs 325 as on June 4, 2014.

Industry watchers are bullish. According to them, there is little doubt that once economic recovery kicks in, Titan will be well-positioned to grow at a brisk 20 percent clip. Investor Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, who owns 7 percent of the company, also said in a recent interview to CNBC-TV18 that “Titan is undoubtedly the best play on consumption in the country”. This confidence stems from hard facts: Titan is the fifth-largest watch manufacturer in the world it sells 13 million watches a year, out of a total 42 million watches sold in India, and is still enjoying healthy growth in a category that is often written off as mature.

The real trigger for growth, though, has come from the jewellery business which contributed 81 percent to the company’s topline in FY2014. Tanishq, it is widely acknowledged, has never had a stronger brand proposition. This is a marked change from 1996 when the first Tanishq store was set up and from 2001 when the board, dissatisfied with its performance, threatened to pull the plug.

Cut to the present, and an impressed investor community is wondering if Titan can possibly incubate another Tanishq. Eyewear retail chain Titan Eye Plus, launched in 2006, may never play in the same league (scale-wise, because of the smaller size of the market) as Tanishq, but it is on track to break even this year.

Last quarter same-store sales growth was 21 percent while overall growth was 35 percent. These businesses, along with the Fastrack range of accessories, are enough to power Titan to its target 20 percent year-on-year growth, say senior management officials. And, for a company that almost collapsed in its effort to make Tanishq viable, this is a fair ambition.

In the early 1980s, Tata veteran Xerxes Desai had decided to take on the challenge of founding India’s third homegrown watch brand after HMT and Allwyn. Titan, when it was launched in 1983, found unexpected—the Tatas had not seen much success in consumer-facing businesses—acceptance in the market. The company set unprecedented benchmarks in design, quality and retailing. For instance, it launched with five times the number of watch models than its nearest rival HMT. “We were the first to have a national selling price, something unheard of in those days,” says HG Raghunath, CEO of the watches & accessories division. By the late 1990s, one-time market leader HMT was perceived as an also-ran, as Titan became a brand to aspire to.

Success bred confidence. Titan sought its next challenge—jewellery, a natural extension to the watch business. The branded jewellery market, now pegged at Rs 1 lakh crore, was a significant opportunity even then. But the path to Tanishq had an ambitious and expensive detour, selling jewellery in Europe in the mid-1990s. High-end designers, retail space and management bandwidth came at a high cost and with little to no returns. Very quickly, Titan retraced its steps back to India and, finally, to the first Tanishq store in Chennai in 1996.

But Desai and the freshly-minted Tanishq brand struggled with a viable business model. For one, the westernised designs did not appeal to Indian consumers. However, the serious concern was the low margins which were—and continue to be— less than half of what the watch division makes. With robustness in profits a distant dream, by 2001 the board started questioning the rationale of staying in this business.

The threat, however, was warded off by Desai, a larger-than-life personality. His retirement, though, soon followed, and the onerous task of proving Tanishq’s worth to the promoters was handed over to Bhat who took over as managing director in 2002.

It helped that Bhat was a founding employee. He had joined the business at a nascent stage when it was known as the Tata Watch Project. Over the next two decades, he worked across various verticals including sales and marketing, HR and international business.

Bhat had cut his teeth and was trained to fix Tanishq. And the right steps were taken. By the end of the decade, the division had become a lean machine capable of consistently clocking high rates of growth. (His success was in no small measure aided by the rising gold price, which rose from Rs 4,400 for 10 gm in 2000 to Rs 31,799 in 2012. It has since fallen to Rs 26,354 as of June 4, 2014.)

To counter the low margins in the jewellery business, Tanishq showed immense working capital discipline. This resulted in over Rs 1,000 crore in free cash each year.

![mg_76200_titan_growth_280x210.jpg mg_76200_titan_growth_280x210.jpg]()

This was also helped by Tanishq’s ability to lease gold from various nominated agencies. The gold was then forward sold for a period of six months, during which time the jewellery found customers. Titan, thereafter, was able to pay for the gold. (In June 2013, in order to reduce the current account deficit, the government clamped down on this practice and asked companies to pay upfront. This elongated Tanishq’s working capital cycle. However, the curbs have since been lifted.)

Further, even though it is among the country’s largest retailers with 1,078 stores and 1.5 million sq ft of retail space, Tanishq’s franchisee-led model meant the business was very asset light.

“They really are the masters of 2,000 sq ft retail,” says Nikhil Vora of Sixth Sense Ventures in a December 2013 interview to Forbes India. But on a hot afternoon in April 2011, Titan was busy disrupting its own strategy. In the Mumbai suburb of Andheri, the company inaugurated a 22,000 sq ft Tanishq store, just a few months after a similar large format store was launched in Chennai. In true Titan style, it pulled out all stops for the event. Bollywood icon Amitabh Bachchan was called upon to cut the red ribbon.

Spread over four floors, the store showcased the finest jewellery designs for its customers. It even had a secluded room to provide privacy to diamond shoppers. In case a customer was in the mood to make an impulsive splurge, the store had a range that retailed for just under Rs 5 lakh, the upper limit for transactions without a PAN card.

However, despite the bells and whistles, the Andheri store and six others like it around the country did not achieve any great success. As consumer spending slowed, so did expectations from these outlets. High fixed costs, including rentals and a staff strength of 70 to 100 people, meant they had to sell substantially more to break even. It was a conundrum: To pull the plug or not. But Bhat decided to back the idea and his team. As a former employee describes it, “Bhat may not always agree but he gives his people a free hand and then internalises their actions.” However, while Titan persisted with the stores, it decided to also utilise them as consumer laboratories.

This exercise underscored the significance of these stores as brand showcases: The company realised that size had a disproportionate impact on the consumer’s mind, to the extent that the buyer would often be influenced into spending more than budgeted. Also, average ticket sizes were much higher.

Though Titan declined to state the exact figure, industry watchers say it is safe to assume there is a 20 percent jump in ticket prices at the large format store over the average ticket price of Rs 70,000 at the 2,000 sq ft stores. Additionally, according to CK Venkataraman, chief executive of the jewellery division, diamonds accounted for 37 to 40 percent of sales at the larger stores compared to the standard outlets where they stood at 27 to 40 percent.

This is vital because diamonds have three times the margins as gold jewellery. Consider Titan’s long-standing quandary: While the jewellery business accounts for the majority of revenue, at 7 percent post-tax margins (with 10 percent as its outer limit), it is only half as profitable as the watch business. The projection is that as the economy recovers, the large stores could prove to be the sharpest weapon in Titan’s arsenal. The math is simple. For the first 15 years, Tanishq was largely a small format store. But when consumer sentiment is on a high, one large 20,000 sq ft store will inevitably be more profitable than ten 2,000 sq ft stores. The small format stores will continue to do their job but the larger ones, with their incremental diamond share, will account for the kicker.

Titan’s attention is now also on another opportunity—a Rs 30,000 crore market—that the company is struggling to exploit: Small-town India’s jewellery demands.

![mg_76208_titan_280x210.jpg mg_76208_titan_280x210.jpg]()

Goldplus, a brand created for this purpose, has (by the company’s own admission) not done very well. Titan has found it difficult to complete with smaller jewellers who operate on lower margins. Venkataraman admits, “We haven’t been able to play out the difference between our brand and others.”

At the other end of the market, Titan has also created a premium brand, Zoya, targeting the buyer who “vacations in Peru and buys Rs 5 crore villas”. It has proved ineffective so far with just two stores, it is too small to have an impact on sales and profits. However, despite the smaller scale, it is a high-margin category and should Titan reach an optimal business model, this could prove margin accretive in the future.

While jewellery grapples with margins, the watch business operates on the robust end of the spectrum. High-end watches that retail for Rs 10,000 yield gross margins of 53 percent. This doesn’t dip below 40 percent even for cheaper watches. At 15 percent post-tax, watches comprise the company’s most profitable segment.

The problem here is that of a shift in consumer need. As Raghunath puts it, “The cellphone is gradually replacing the watch.”

To counter this challenge, enter Fastrack. The brand, which falls under the watches division, has rolled out a host of products in the last decade—sunglasses, bags, belts, wallets and helmets. A range of perfumes, Skinn, has also been introduced.

At 13 to 14 percent margins, both these businesses are as profitable as watches and a natural fit for this division. Interviews with senior management suggest that the company is banking on them to contribute significantly to profits in the years to come. Jhunjhunwala, too, believes these categories will allow the company to maintain a robust pace of growth.

The Fastrack business, in fact, has a significant role in Titan’s future strategy. The plan is to increase the number of its stores from the current 142 to over 500 in the next few years.

![mg_76204_titan_profit_280x210.jpg mg_76204_titan_profit_280x210.jpg]()

Bhat’s philosophy of taking Titan into categories that have a large mass of unorganised players, and where design plays an important role, has also led it to the prescription eyewear business. The idea of Titan Eye Plus initially came from the watch division while they were working on sunglasses under the Fastrack brand. But on deeper exploration, they realised it was an under-penetrated category with unreliable service quality. And it had obvious synergies with Titan’s strengths in the retail and design space.

A survey showed while 450 million Indians needed vision correction, only 25 percent used optical lenses. Urban customers were willing to pay a premium for reliable testing and error-free frames. Using this framework, the company started crafting a business plan. Every ophthalmologist working for Titan Eye Plus has to undergo a four-month training programme at its facilities in Hosur.

The company has since also set up a unit to produce lenses that are resistant to water, dust and scratches.

This journey, since 2007 when the first Titan Eye Plus store was set up, was marked by the hardships typically faced by an organised player which enters a segment traditionally dominated by unorganised retailers. For example, inability to provide ad-hoc discounts which are meaningful for customer loyalty. The board was initially reluctant to enter this category. But the plans and the prospect of breaking even in six to seven years convinced them. Plus, though the addressable market (at Rs 3,500 crore) may not be of the same scale as jewellery, but S Ravi Kant, CEO of the eyewear business, says, “I cannot share the exact margin but can tell you that this is the highest gross margin business in the company.”

In a short time, Titan Eye Plus has built a solid brand name. It is also on track to break even once it reaches Rs 300 crore in turnover (it is currently at Rs 200 crore) a year from now.

What’s next? That’s the question that typically follows any success story. In Titan’s case, the jury is still out. Some observers say that Titan can well become a victim of its own success. No matter how hard it tries, it will always be disproportionately dependent on Tanishq, they point out.

Interviews with several investors who have tracked Titan for a long time led to another perspective: Since Tanishq has been so successful, why not focus exclusively on it? It’s an argument Bhat dismisses. “The company would be hugely risked as it was when consumer sentiment weakened last year. Plus watches and accessories have higher margins than jewellery,” he says. Very clearly, Titan is a company that operates in the lifestyle space and Bhat intends to keep it that way.

His eyes are fixed on the numbers. A 15 to 20 percent growth in the medium term is par for the course but that would be a climb down from the 23 percent growth in topline and 30.5 percent growth in bottomline since 2001. But as Bijou Kurien, former chief executive (lifestyle) of Reliance Retail, explains, none of the new categories the company has entered are of substantial size. And he’s uncertain if people will pay more for the stylish helmets being produced by Fastrack. “The company needs to look for big ideas. These small fledgling ideas are a distraction,” he says.

A July 2013 amendment to the memorandum of association of the company says Titan could look at manufacturing, selling and retailing items as diverse as apparels, sarees, kitchen utensils, chimneys and solar panels.

However, the reality is none of these categories have the heft and scale of Tanishq. For now, the opportunities provided by an economy on the mend and Titan’s spruced up business lines will keep Bhat busy for the next five years.