ByteDance to the music

The super-unicorn's Douyin video site is cutting in on WeChat's hold on Chinese youth

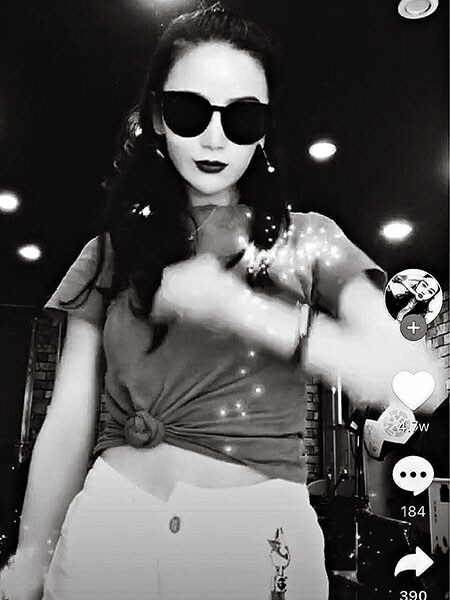

Shake it till you break it: Music app Douyin lets users have their 15 seconds of fame, sounding a sour note for rival Tencent

Shake it till you break it: Music app Douyin lets users have their 15 seconds of fame, sounding a sour note for rival Tencent

Athena Yang learnt about Douyin from her boyfriend and soon became hooked. The 29-year-old, who works at an investment firm in Beijing, now spends her lunch break and evening watching music videos on the app, where people post 15-second clips of themselves—dancing, singing or even applying make-up. “There is a lot of funny and creative stuff on Douyin,” Yang finds. “It is really relaxing and helps to relieve stress at work.”

Developed by Beijing ByteDance Technology, Douyin, also known as Tik Tok, has taken China’s younger generation by storm. Similar to the popular music app Musical.ly, which ByteDance acquired for $1 billion last year, it allows users to make, edit and broadcast short video clips to their favourite songs, while using an algorithm to promote them in individually tailored feeds. Now Douyin’s explosive popularity is giving ByteDance—a $20 billion startup also known for the Toutiao news app—an edge as it contends with Tencent to become China’s media and entertainment powerhouse. Yet the firm is facing YouTube-like challenges: Some of Douyin’s clips are drawing scrutiny and a backlash online for inappropriate and potentially dangerous content, adding to the regulatory grief ByteDance already faces.

Douyin’s recent success comes from its content production mechanism. As with most short-video platforms in China, it relies on clips made by both professionals and amateurs to attract eyeballs. But ByteDance does it better than local peers: Douyin regularly invites social media stars to participate in company-hosted online video contests, where they challenge each other or ask followers to broadcast clips to a certain theme. This has given rise to viral online trends that upped the app’s popularity.

For example, some 70,000 app users once raced to make humorous moves to the song “Seaweed Dance” by Chinese artist Xiao Quan—a craze that inspired countless internet memes and offline dancing contests across China. Douyin selects the most popular moves to put in personalised feeds. And some online stars, such as 25-year-old music producer Zhou Yue, tell Forbes Asia they can earn millions of yuan a year by making videos for Douyin. Advertisers like automobile companies and gaming studios are paying to work with them on related promotional songs that are shared across the site.

“Douyin has been producing better-quality content than other short-video platforms in China,” says Chen Yuetian, a partner at Chinese investment firm S Capital. “Its clips are more fashionable and attractive to young people.”

A year and half after its launch, Douyin has attracted 166 million active users, a majority of them under 30, according to Beijing consultancy Analysys International. They spend an average of 12.6 hours inside the app monthly—an engagement level surpassing the 12.3 hours spent at Tencent-backed video-sharing site Kuaishou, the firm’s data show. Meanwhile, Douyin has been topping the downloading chart at the China iOS Store for months, and it even became the most downloaded non-game free app worldwide in the first quarter this year—an accolade previously held by Facebook’s WhatsApp, according to US research firm Sensor Tower.

The popularity is being felt at Tencent. The Shenzhen tech giant has been building its own entertainment empire, often using the super-app WeChat to direct people to Tencent-offered text or video services such as Weishi, a mini-video platform the company revived in April after launching it in 2014. WeChat has also been adding more video elements, such as allowing users to upload longer clips to their friend circles to increase engagement.

But as people spend more time on Douyin, their attention is being diverted from WeChat—where Tencent wants to keep them for more selling. According to Questmobile, a Chinese data analytics firm, short-form video accounted for 7.4 percent of the total time Chinese people spent online in March, up from 1.5 percent a year ago. Meanwhile, instant-messaging services, primarily WeChat, are down to 32 percent from 37 percent in the same period. “Short-form video apps like Douyin are putting pressure on WeChat,” says Zhang Xueru, an analyst at Shanghai’s 86 Research. “They are all competing for users’ leisure time, but it is now increasingly occupied by Douyin.”

undefinedDouyin has attracted 166 million active users, a majority of them under 30. It even became the most downloaded non-game free app worldwide in the first quarter this year[/bq]

ByteDance and Tencent are taking their clashes to court. The two companies recently filed a series of lawsuits against each other for defamation and unfair competition, with Tencent demanding one yuan ($0.16) in damages and public apologies on ByteDance’s platforms. ByteDance is asking for 90 million yuan in damages, accusing Tencent of purposely blocking its content on the popular QQ messaging app. ByteDance founder and chairman Zhang Yiming, 34, also engaged in a rare online spat with Tencent founder Pony Ma, accusing the latter’s Weishi app of plagiarising Douyin’s model. ByteDance and Tencent didn’t respond to Forbes Asia’s requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Douyin has other issues. In Hong Kong the app has been drawing a backlash for what some consider inadequate protection for underage children, who are uploading clips containing violent and sexually suggestive scenes to gain online fame. What’s more, the state-run People’s Daily is calling for stricter oversight of the app, after press reports that some users were seriously injured by imitating Douyin videos. Douyin responded publicly by saying some dance or sport moves “are not suitable to be imitated by all users” it urged parents to take care and said the app would include “risk warning systems”.

These come as ByteDance is already mired in a regulatory quagmire. China’s ministry of culture and tourism has just launched a formal investigation of the company for publishing a comic series that it said distorted Chinese history. (ByteDance took it down with an apology.) In April, authorities also told the company to permanently shut down its popular joke-sharing app Neihan Duanzi, which the country’s media watchdog criticised for promoting “vulgar and improper content”. In a public apology letter, Zhang said the product “walked the wrong path” and promised to hire 10,000 people to police his sites.

Competition is also heating up. In addition to Tencent, China’s internet giants are all tapping short-form video to capture young users. The Baidu-backed iQiyi, for example, recently launched its own mini-video app Nadou, using artificial-intelligence-based software to analyse online trends and edit related clips. This may force ByteDance to bolster marketing to promote its own service, potentially hurting margins, 86 Research’s Zhang says.

“They need to generate more good content to build an online community,” Zhang says. “Regulation is one thing, but what determines how far this product can go is whether it can add more social elements, so users can become better engaged.”

First Published: Sep 19, 2018, 15:00

Subscribe Now