France's big pivot

Take a centrist president with a mandate and a private sector background, mix in the country's top tech billionaire with the world's best incubator, and the potential is tantalising: Can they transfor

The epicenter: Station F in Paris

The epicenter: Station F in Paris

Image: Levon Biss for Forbes

The world’s largest startup incubator sits inside the bowels of a nearly-century-old former freight station, where 3,000 nascent entrepreneurs dart across the 366,000 square feet like cash-hungry ants. More than 30 venture capital firms, from Accel Partners to Index Ventures, pay a $6,100-a-year membership fee for the privilege of making investments on-site Facebook and Microsoft run programmes to try out companies they might buy Amazon and Google focus on sussing out talent.

Walking around, you see a $20 million installation by Jeff Koons, floating meeting cubes and a blacked-out “relaxation zone”, where overtired programmers leave their shoes outside. “People sleep in here sometimes,” says Roxanne Varza, a California native who runs the incubator, pulling back a curtain to find a young woman doing exactly that.

The most impressive feature, however, is the ground under this complex, known as Station F. That’s F as in France—the project sits in Paris, the capital of a country known as much for constant strikes, mandatory 35-hour workweeks and expensive labour as for the Eiffel Tower and tarte tatin. In France, the payroll tax sits at 42 percent, with labour laws so convoluted they’ve been inscribed in a red, 3,000-page tome called the Code du Travail. Over the years, few western democracies have proved less hospitable to entrepreneurship and growth.

Station F, which opened a year ago, has an edifice’s version of a new-car smell, providing a big fat counter-narrative. “The classical way for three or four decades in France to react to change is to claim that we will resist the change,” says French president Emmanuel Macron, in an exclusive interview with Forbes. The world took notice last year when Macron, at 39, became the youngest president ever elected in France. But his age is less important than his background: Before politics, Macron spent more than three years as an investment banker at Rothschild and also tried to develop an education startup. French politicians, from Chirac to Hollande, have blathered about reform for decades, only to succumb to pressure from change-averse pensioners and myopic unions. Macron gets it, and has staked his entire presidency on delivering. “Perhaps some of them will want to organise strikes for weeks or months. We have to organise ourselves,” the president says. “But I will not abandon or diminish the ambition of the reform, because there is no other choice.” The leader: Can France’s first entrepreneurial president top the forces of inertia?

The leader: Can France’s first entrepreneurial president top the forces of inertia?

Image: Levon Biss for ForbesUsing executive orders, he’s quickly pushed through a raft of new employment laws, making it easier to hire—and fire. To add some honey to the medicine, he’s also put $18 billion into professional retraining over the next five years, including a controversial extension of unemployment insurance for France’s growing number of self-employed and small business owners. He’s slashing at taxes on wealth, capital gains and worker compensation, and “simplifying everything”.

How far is Macron willing to go? He reveals to Forbes that next year he intends to permanently end France’s notorious 30 percent “exit tax” on entrepreneurs who try to take money out of France—a tremendous disincentive for foreigners to start a business there and a strong incentive for French citizens to launch elsewhere. In doing so, he’s moving in the opposite direction of US President [Donald] Trump, who has gleefully threatened American companies who expand abroad and promised subsidies for those who stay.

“People are free to invest where they want,” says Macron. “If you want to get married, you should not explain to your partner, ‘If you marry me, you will not be free to divorce’. I’m not so sure it is the best way to have a lady or a man who loves. So I’m for being free to get married and free to divorce.”

These enlightened policies come just in time. Demographically, France will surpass Germany as Europe’s most populous country within this generation, and it’s an educated lot, rating with the continent’s best educated, with a slew of elite engineering schools to boot. “France is extremely well-positioned from a growth perspective,” says Jonas Prising, CEO of ManpowerGroup. At the same time, the competition is heading the wrong way: As it stumbles toward Brexit, Britain continues to deepen the largest self-inflicted wound in modern economic history. Merkel remains politically hobbled by her weakened coalition. And while Trump crows about the strong US economy, his protectionist trade policies have more in common with Smoot and Hawley than with Reagan and Clinton.

Macronomics is already having an impact. As soon his labour reforms passed in January, the French retail giant Carrefour and the carmaker Groupe PSA announced 4,600 job cuts. Strikes ensued, naturellement. But in the same time period, foreign entities announced up to $12.2 billion in new investments, Macron’s economic advisors say. Disney is budgeting $2.4 billion to expand Disneyland Paris Germany’s SAP is putting $2.4 billion into R&D centres and startup accelerators Facebook and Google are scouring the French capital to hire 150 new specialists in Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Startup life here is improving too. While uncertainty around Brexit undermines London venture capital, French funds, for the first time ever, were outraising the rest of Europe last year, according to the most recent data from market intelligence firm Dealroom. In January, French startups had the biggest foreign representation at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, falling just six shy of the US total.

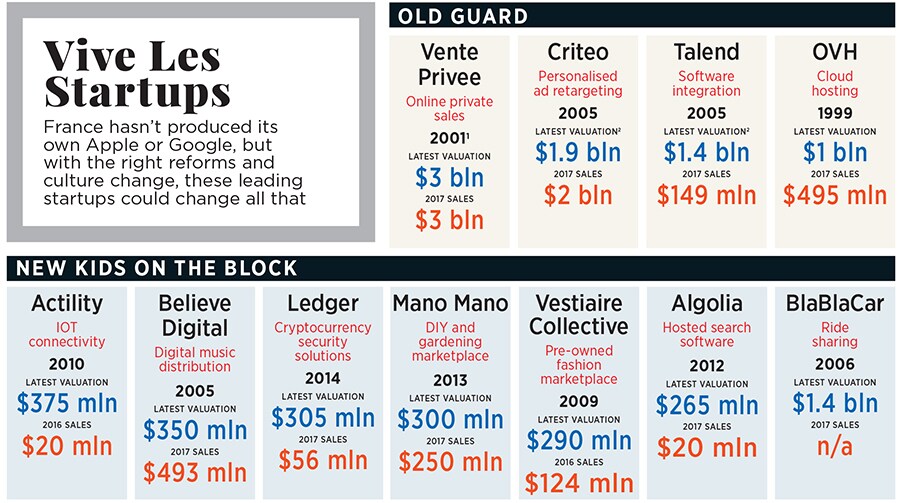

Perspective remains important. In 2017, France had only three startups valued at $1 billion, versus 22 unicorns in the UK and 105 in the US. Decades of cultural anti-entrepreneurship can’t be instantly turned off. But the ingredients for change are here. “Countries that we think are very slow are now moving ten times faster than we are,” says John Chambers, the former CEO of Cisco, who pushed through $200 million in investment in French startups before leaving that role in 2015, adding that France now has “the right leader at the right point in time”. London investor Saul Klein, who recently invested in a spin-out of British startup success Deliveroo that went on to chase the burgeoning French market, notes that he sits within walking distance of the Paris-bound Eurostar rail service: “It’s closer than Edinburgh or Dublin.”

In the technology era, France has endured a series of Lost Generations. As Gates and Jobs and Ellison begat Musk and Bezos and Zuckerberg, France’s best entrepreneurial minds looked at their domestic opportunities and then booked a ticket to California to work for the Americans. There are some 60,000 French citizens working in Silicon Valley, more than from Britain, Germany or any other country in Europe.

The catalyst: Billionaire Xavier Niel has gone from outcast to Pied Piper

Vincent Isore / Ip3 / Getty Images

The only major exception: Xavier Niel, France’s eighth-richest man, with an estimated fortune of $8.1 billion. The country’s 40 billionaires have two dominant sources of wealth: Luxury/retail or inheritance (or, for many, both). Niel is the only one with roots in the internet. Since this is France, his original angle was l’amour. Or, as they say in internet-speak, porn. France was an early adopter of a 1980s internet forerunner pushed by the French telecom monopoly. As a 17-year-old hacker, Niel forged his father’s signature to get a second phone line installed and developed a pseudonymous chatroom that focussed on sex. By 24, he’d sold an online publishing company for more than $300,000. And in 1994, when the World Wide Web was emerging, Niel lauched Worldnet, France’s first mainstream internet service, giving away millions of connection kits via magazines the way Steve Case was doing with AOL in the US. As with Case, his timing was impeccable: He sold Worldnet for more than $50 million in 2000, right before the dotcom crash.But while that kind of story would have made him a hero in Silicon Valley, Niel, with his middle-class background and lack of formal education, was eschewed by the French business elite. “People didn’t like entrepreneurs much,” says Loïc Le Meur, the founder of LeWeb conference, who started several French tech companies before fleeing to Silicon Valley. “If you succeeded you were not celebrated. You were more like a problem.” They called Niel the pornocrat, and executives refused to be seen in public with him. “I forgot all the bad things,” Niel says of those days. But back then Niel embraced the pirate’s mantle, eventually scoring billions through telecom Iliad, which, with its half-price contracts, has carved into France’s calcified mobile industry over the past decade.

Fantastically rich, in 2013 he netted $400 million by selling 3 percent of Iliad’s stock and set out to cultivate more French entrepreneurs like himself. If real change in France is impossible without political leadership, it’s equally true that government policies can’t move the needle if the private sector isn’t ready to respond. In Niel, Macron found a ready-made partner. Niel’s first big expenditure: $57 million to create 42, a free non-profit school in Paris that has taught coding to 3,500 students, 40 percent of whom never finished high school. “42 was one of the most impressive things I’ve ever seen,” says Phil Libin, co-founder of productivity app Evernote. (In 2016, buoyed by its success, Niel launched a far larger outpost of 42—named after the Douglas Adams joke that “the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything is 42”—just outside of San Francisco, in Fremont.)

The expat: Former Apple whiz kid Tony Fadell now calls Station F home

Image: Levon Biss for ForbesFrom there, Niel launched Kima Ventures to back startups, with a focus on France, bringing in former M&A advisor Jean de La Rochebrochard to run it. De La Rochebrochard quickly suggested investing more money in fewer companies and doubling down on winners, a notion Niel dismissed out of hand: “I don’t need more money. I’m just doing this because it’s exciting, it’s useful and nobody is doing it.” Kima now claims to be the most active angel fund in the world, with 518 investments over the past eight years, according to Pitchbook. De La Rochebrochard says he sees Niel only once or twice a year but hears from him constantly, sometimes asking business school audiences to email Niel and see if he responds within two hours. “Every single time he does,” says De La Rochebrochard.

The prospect of hundreds of French investments would have once been preposterous in a country teeming with overprotective laws that serve the work-shy. Simply leasing an apartment in Paris is a struggle thanks to woefully inflexible property rules lacking the slip of paper that proves you have one of France’s sacred full-time employment contracts, entrepreneurs and startup employees often find themselves at the back of the line for housing. Employees must give up to two months’ notice if they want to leave, and employers are stuck with them. As recently as a few months before Macron’s inauguration, France implemented a “right to disconnect” law, giving employees a legal mandate—and incentive—to ignore late-night emails.

Furthermore, there was no hub for entrepreneurial activity. The closest Paris had was the Sentier district, the fashion quarter, where dwindling retail prospects allowed for short-term rentals.

Around this time, Niel met Varza, a young Californian who ran Microsoft’s startup programme Bizspark in France. In July 2013 he sent her an email, subject line “Bonjour Roxanne”, offering to foot the bill if she scouted the world’s best startup spaces. Varza emailed her photos and notes to Niel, who then forwarded them to his architect, Jean-Michel Wilmotte, with the instruction to take the best features even further.

Niel is the sole bankroller. He spent more than $300 million to build out Station F and three nearby apartment blocks, which can house 600 entrepreneurs, and added “a few hundred [million] more” for a five-star and a budget hotel being built next door. “It’s completely philanthropy,” he says, standing next to the colorful Koons work that resident entrepreneurs have nicknamed “the unicorn poo”. “This is a gift.”

To gain entry to Station F, startups apply for one of 32 themed programmes: Microsoft takes ten AI startups, Facebook grabs 15 in data, and so on. “They got access to a startup, we got access to their data,” says digital health insurance entrepreneur Jean-Charles Samuelian, who leveraged that Facebook programme into a $28 million raise announced this April. For Station F’s in-house programme, some 4,000 startups from 50 countries applied last year 200 got in.

Amid all this activity, investors float around, service providers offer everything from shipping to 3-D printing, and the French government has set up something of a concierge space, where entrepreneurs cut through the red tape to get their business licence and tax forms in one place. “It’s like a drive-through American restaurant,” says Tony Fadell, the legendary Apple executive who helped invent the iPod. Fadell then started and sold (for $3.2 billion) the thermostat company Nest as a second act and in 2016 moved his family to Paris as a third act. He’s a completely new type of expat, ensconced in Station F, investing in startups. Similarly, Evernote’s Libin has decided to base a European startup studio out of Station F: “There’s something in the culture that bubbles up really exceptional individuals.”As the sounds of snapping cameras and chattering crowds echoed through Station F on the day it launched, Emmanuel Macron, dressed in a dark suit, asked Antoine Martin, one of France’s newest and most successful entrepreneurs, how he’d built location-tracker Zenly, which he’d just sold to Snap for $213 million. It wasn’t easy, Martin explained in French. At one point he had to pivot the entire business.

“Pivot?” interrupted the president.

Niel, who was nearby, quickly clarified, since “pivot” in French strictly connotes physical movement, not a shift in business strategy. Half an hour later, when Macron went in front of the hundreds of startup founders and software engineers who populate Station F, their phones held aloft, he told a story about promising his wife three years ago that he would become an entrepreneur. But things had changed.

“Je pivote le business model,” he said, prompting laughter and cheers.

Macron really knows how to pivot, which gives him a chance to do what his predecessors couldn’t. The son of two doctors and the product of universities that churn out France’s ruling elite, he has the kind of establishment credibility Niel never did. Early in his career, he served as an assistant to Paul Ricoeur, a French philosopher whose life work was finding balance between extreme opposing views. Putting that to use, he worked as a banker at Rothschild, where at 34 he earned more than $3 million advising Swiss consumer-goods giant Nestlé on its $11.8 billion bid for Pfizer’s baby-formula business, even wrestling it away from France’s Danone. He then joined the leadership team of a socialist government, led by François Hollande.

At first he was a deputy chief of staff, but then in August 2014 he was named economic minister, charged with pushing early versions of the reforms he’s now seeing through. Between those stints, he began to develop ideas for an education startup. “I think I understand entrepreneurs and risk-takers quite well,” says the president.

Macron used his brief government stint effectively. “He was asking about what makes Silicon Valley successful,” says Chambers, recalling a dinner he hosted for Macron and other French startup founders in Palo Alto. They talked about why Boston’s Route 128 lost the tech-hub crown to the Bay Area. “He was just learning it. He was absorbing.”

Macron started the political party En Marche to solve the “blockages” that have held France back. He quickly found himself with an incredibly fortuitous hand. His centrist platform breaks some of the left-right political paralysis, allowing him to, say, push labour market reform at the same time he moves to subsidise the vulnerable. Crucially, since both he and his legislative majority are locked in until 2022, he can make the long-term decisions the way president-for-life types like China’s Xi and Russia’s Putin tend to, but with the democratic, free market ideals of a western capitalist.

The latter trait, as widely noted during his recent state visit to Washington, gives him a natural rapport with Trump. “I understand very easily this kind of person,” Macron says. “When you see him as a dealmaker, as he has always been, it’s very consistent. That’s why I like him…That’s where my business background helped me a lot.”

But those business backgrounds are also quite different. Trump’s real estate dealmaking always had an I-win-you-lose ethos to it, whereas Macron the banker needed to foster coalitions. “We have a difference in terms of philosophy and concepts regarding the current globalisation,” Macron says. And he’s using that to his advantage. After Trump began turning his back on renewables last year, Macron publicly pounced, imploring green-tech entrepreneurs and academics to come to France and, tongue firmly in cheek, “Make Our Planet Great Again”. Two thirds of the ensuing 1,822 applications for grants came from the US. “If you are in a country where the strategy is not clear regarding climate change, that’s a big issue for many startups,” says Macron, who has been similarly effusive about luring British financial firms.

If Station F represents a renaissance in French entrepreneurship, then dinner time at Station F represents the hurdles to come. The place “empties out by 7 pm”, says Karen Ko, who came to Paris for her MBA and now helps run a data analytics startup for care homes at Niel’s giant incubator. “By 8, it’s almost a ghost town.” Meanwhile, David Chermont, of Inbound Capital in Paris, is surely the only startup advisor to say this: “People should stop fantasising about startups. It’s really hard. You’re going to bed with work in your head.”

Ask anyone at a French startup: Cultural and government habits die hard. At first it was a breeze when Anton Soulier incorporated Mission Food in Paris last year. But then a bill came in the mail. His food-delivery startup had to pay nearly $2,000 in employment tax—before he’d hired a single employee. “Crazy,” he says. In France there’s a de facto legal tax, with every startup needing a good lawyer to the tune of more than $30,000 a year just to navigate the byzantine regulations. When the nascent companies eventually hire staff, each employee’s salary costs will double because of various contributions mandates. And good luck deciphering the pay slips, which have 25 lines of deductions and figures.

President Macron says he’s working on it. “We are basically killing a lot of small taxes that our entrepreneurs had to pay,” he says. But some entrepreneurs are sceptical those changes will come once all the hype dies down. Macron’s reforms haven’t had an effect on Mission Food, Soulier says, noting that some labour law changes from 2002 are only now coming into effect, over 15 years later.

France’s past governments have also been notorious for siding with legacy industries, like the taxi trade, and against newer business models like ride-sharing. “I want this country to be open to disruption and these new models,” says Macron, who then idealistically says the answer is compromise. “My startups create some issues for my big companies like EDF,” he says of the electric utility firm. “But I’m fine with that. And I told EDF, ‘You should invest in this company. Perhaps they will disrupt you. So the best way to proceed is to be a partner’.”

A sound idea, but it’s hard for a government to guide the strategy of former monopolies. “[Macron] hasn’t walked the walk,” says disappointed Macron fan Yan Hascoet, who co-founded Uber competitor Chauffeur Privé. His startup lost almost a third of its 15,000 drivers in 2017 when regulators rolled out an ultra-difficult theory exam in an obvious move to shield the older taxi drivers, who were clogging Paris in protest. “He chose not to touch this topic.”

Macron’s broader problem is getting the rest of his government—and the pockets of entrenched support for incumbents like the taxi trade—on board. The cynical Niel, who proclaims that he doesn’t vote, not even for Macron, understandably thinks true reform will come from the entrepreneurs. But reform requires noise, and French entrepreneurs don’t always like making it. Money is still “negatively connotated here”, says Zenly’s Martin, who says he and his co-founder are staying “out of the sunlight” after their sale to Snap. In the last three years, Nicolas Steegmann sold his startup Stupeflix to GoPro Pierre Valade sold Sunrise to Microsoft and Jean-Daniel Guyot sold Captain Train to Trainline. They are “all unknown to the general public”, says Martin. And “all have done nine-figure deals.”

Foreigners are more comfortable with the spotlight, and they see progress. “There is a certain informality here,” says Ko, perched on a lime-green cushioned bench in the middle of Station F. “It’s very un-French. You can walk around, you can start a conversation and introduce yourself. I like that because it makes me feel like I’m home.”

Silicon Valley became a force because its alumni helped each generation grow, says Fadell. “Station F and Paris will experience the same multiplier effect.” Among the new alumni, star founders from Criteo (an ad-tech giant that went public in 2013 and is now worth $1.9 billion) and ride-sharing app BlaBlaCar (still private but valued at $1.4 billion) have already become angel investors for the next generation of Parisian startups.

More are coming: International Station F applicants cite Silicon Valley costs, Donald Trump and Brexit as their reason to apply, and all three of those seem fixed for now. France would historically squander such gifts it’s why Macron moves with such urgency. “Most of the time, leaders decide to reform at the end of their mandate,” he says. Instead, he front-loaded his major initiatives. “Something we have to deliver today is not to be passed tomorrow,” he says. “Late is too late.”

First Published: Jun 06, 2018, 12:40

Subscribe Now