Meet the secretive billionaire who makes the cheese for Pizza Hut

From Pizza Hut and Domino's to Little Caesars and Papa John's, the vast majority of pizzas in America feature mozzarella from one company. And the elusive James Leprino leads it

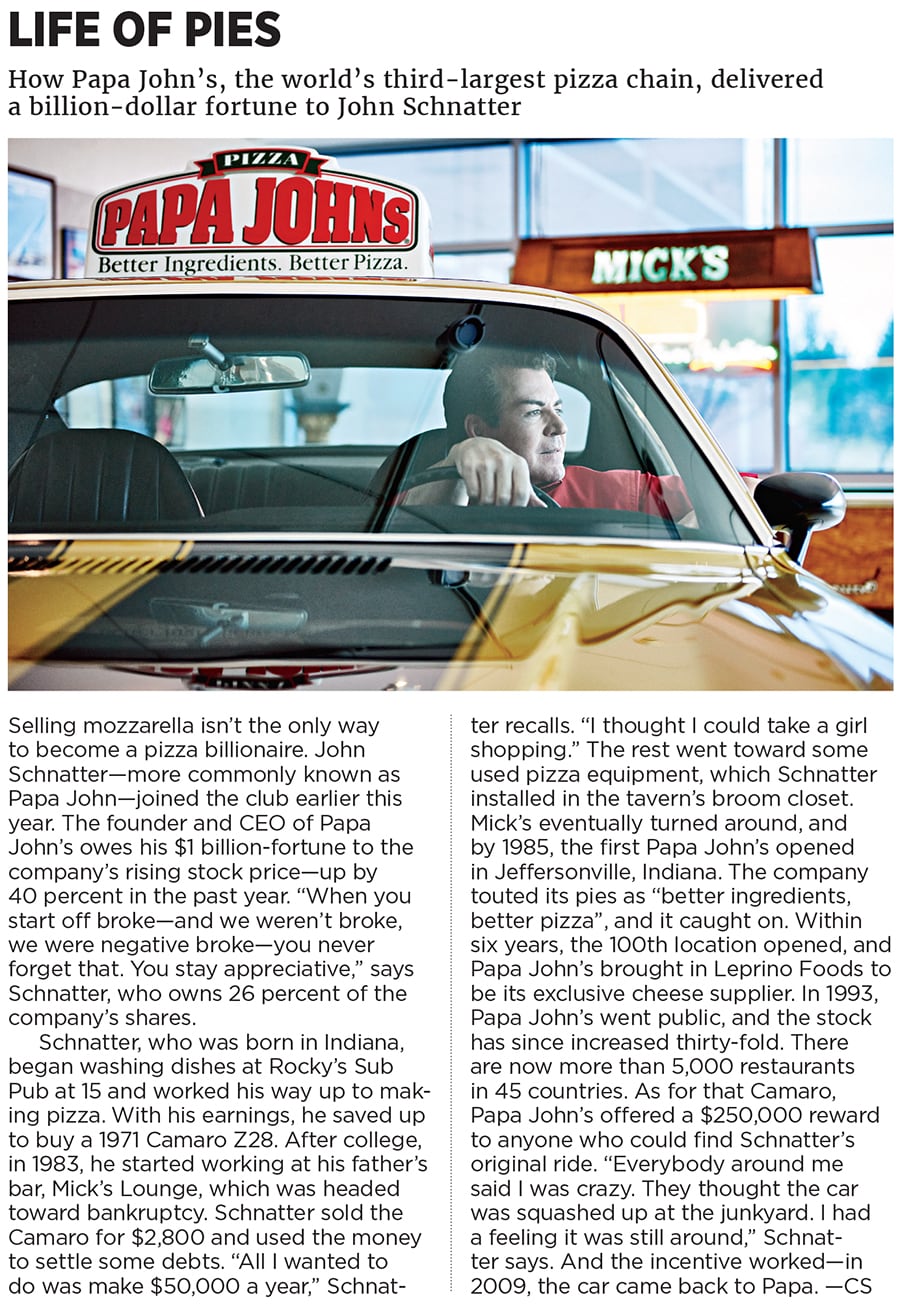

Camera shy: If you Google James Leprino’s picture, you’ll get fellow billionaire John Malone. This 1970s company portrait is the only known image of Leprino Foods’ founder (right)

Image: John Prieto/The Denver Post via Getty Images

An avalanche of cheese pours into the test kitchen at the Denver headquarters of Leprino Foods, the mozzarella supplier to Pizza Hut, Domino’s and Papa John’s. First, thin wisps of low-moisture mozzarella, then a diced alternative, followed by an “artisanal” version, cut short and wide. Then come flavoured cheeses made with a mozzarella base, as well as provolone, cheddar and Monterey Jack.

Cooks bring out a take-and-bake pizza, a New York-style pie and a stuffed crust, fresh from nearly a dozen ovens. Another course features frozen food made with Leprino products, including ham-and-cheddar Hot Pockets, Stouffer’s lasagna and Smart Ones baked ziti. Then come the cheese cubes marketed as snack pairings: Pear flavour with nuts or Gorgonzola with pretzels. Team Leprino next brings out dessert: Salted-caramel-flavoured mozzarella wrapped in hot dough, rolled in cinnamon sugar. After an hour, the plastic shot glasses appear for sampling the company’s lactose and whey powders, which end up in protein bars, Yoplait yogurt, Pillsbury Toaster Strudel and baby formula consumed by millions of infants annually.

Two floors above this dairy deluge, in a dark-wood-panelled office with white marble floors, Corinthian columns and gold accents, sits James Leprino, the Willy Wonka of cheese. “It’s hard for me to believe I agreed to this,” the 79-year-old billionaire says. “I really like to keep my privacy.”

Indeed he does, to a nearly unprecedented degree, given the way he dominates his industry. Leprino has eluded photographers for decades: A Google search picks up photos of fellow Colorado billionaire Philip Anschutz and cosmetics heir Ronald Lauder. There isn’t a single image of Leprino on his company’s website. But after nearly 60 years of running the business and more than a decade on Forbes’s list of billionaires, Leprino, worth an estimated $3 billion, is willing to be interviewed about how his family’s grocery in Denver’s Little Italy became the world’s top producer of pizza cheese—the slightly derisive term competitors use to describe its mozzarella. In all, Leprino Foods sells over a billion pounds of cheese a year, to the tune of $3 billion in revenue.

The little-known Leprino (he declined to be photographed) rates as one of America’s all-time monopolists. He lets others worry about fresh mozzarella balls and pizza that taste like they were made in the old country. His laser focus on large pizza chains has allowed him to control as much as 85 percent of the market for pizza cheese and somehow sell simultaneously to a set of customers—Pizza Hut, Domino’s, Papa John’s and Little Caesars—that try to cut each others’ throat in every way that doesn’t involve where they buy their milk products. Dominating the market has its advantages: He’s able to invest in technology that no run-of-the-mill dairy farmer ever could, resulting in more than 50 patents—and an estimated 7 percent net margin, which dwarfs the dairy-industry average.

As the diamonds of his watch bezel shimmer on his wrist, Leprino takes out his beat-up black leather wallet, removes the rubber band holding it shut and reveals a card featuring the four company watchwords: Quality, service, price, ethics. “I’ve got everybody keeping one in their pocket,” Leprino says. “The company was growing so fast they were missing this important message.”

Quality is listed first intentionally. It’s easy to mock his product (Frankencheese, anyone?), but Leprino Foods is one of the few dairy giants that have never had a recall. Every Monday at 11.30 am, Leprino walks down to the test kitchen along with two dozen of his most trusted executives for the weekly Monday Melts meeting. The executives test samples of the cheese produced for some 300 clients in 40 countries and check every complaint received the week before. “Your employees have got to know you’re not a phony,” he says. “They’ve got to believe in you. Whey to go: Leprino’s new factory is rolling out its first direct-to-consumer product, a protein powder called Ascent

Whey to go: Leprino’s new factory is rolling out its first direct-to-consumer product, a protein powder called Ascent

Image: Cody Pickens For Forbes

“I support what’s going on, but I don’t try to lead it,” he adds. “My job is to hold them responsible for doing what they said they’re going to do.”

He wasn’t always so hands-off. While acknowledging his “genius”, numerous industry executives paint Leprino, in his younger days, as an “aggressive” leader who wasn’t above visiting individual franchise owners to pitch his technologically advanced cheese. But very few will go into detail, and fewer still will attach their name to their comments. One pizza entrepreneur puts it this way about the man who owns 100 percent of this mozzarella giant: “Jim Leprino is a very powerful man.”

Leprino’s office bears testaments to his roots, including a black-and-white photo of his mother on her wedding day at the age of 16 and a bronze relief of James and his father rolling fresh mozzarella balls. Leprino Foods’ genesis lies in the mountains of southern Italy, which Mike Leprino Sr left in 1914, at the age of 16. Accustomed to high altitude, he settled in Denver without much of an education or the ability to read and write English, he began farming. More than three decades later, in 1950, he finally opened a grocery store to sell the produce he grew. Italian specialties followed, including fresh ricotta, mozzarella balls and ravioli made by James’s sister Angie.

Meanwhile, James, the youngest of five children, noticed his classmates spending free time at neighbourhood pizza joints. After graduating from high school in 1956, he started working with his father full-time and shared a revelation: “Pizzerias in this part of the country were buying 5,000 pounds of cheese a week,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘This is a good market to go after’, so I did.” In 1958, after larger chain grocery stores had forced the Leprino market to close, the Leprino Foods cheese empire started with $615.

The timing couldn’t have been better. That same year, the first Pizza Hut opened, in Wichita, Kansas. A year later, Mike and Marian Ilitch opened the first Little Caesars, outside Detroit. Another year went by, and Domino’s began delivering pizza, in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Frozen pizzas, introduced after soldiers returned home from World War II craving slices, were also gaining popularity. After two years in business, Leprino Foods was delivering 200 pounds of block mozzarella a week to local Italian restaurants.

Leprino realised he needed to learn the science behind making cheese on a mass scale. But with a young daughter at home and another baby on the way, he didn’t have time for college. Instead, he hired Lester Kielsmeier, who had run a cheese factory in Wisconsin only to find out that it was sold during his stint in the Air Force during World War II, because his dad believed he’d been killed in action. “When Lester came, I went downtown to the junkyard and I bought a couple of bigger cheese vats to make it look like we were really in the business,” Leprino says.

Leprino’s first coup came in 1968, when Pizza Hut was looking for a supplier that could help it cut costs while standardising portions. After hearing that shredding 5-pound cheese blocks in the franchises was time-consuming and inconsistent, Leprino Foods started selling frozen, pre-sliced blocks. For the first time, pizza-makers could simply layer a few slices onto each pie.While Kielsmeier made the cheese, Leprino fixated on efficiency. He quickly realised he was dumping half his raw ingredients into the river in the form of whey, the calcium-rich liquid left over after curds are strained. Inspired by the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, Leprino travelled to Japan to meet with scientists using milk proteins derived from whey to help the Japanese population grow taller. More than a half-century later, Leprino Foods remains the largest US exporter of lactose, a byproduct of sweet whey, and retains a large market share in Japan.

On the cheese side, Leprino hustled to satisfy Pizza Hut, which went public in 1972 with around 1,000 stores and, at its peak in the 1990s, accounted for 90 percent of Leprino’s sales. Pizza Hut franchises would sometimes wait too long to thaw the pre-sliced mozzarella and reported that their cheese would crumble, so Leprino Foods responded with its first major breakthrough: A preservative mist. The scientists there soon realised that this method allowed them to add flavours such as salted caramel and jalapeño. They could even make a reduced fat “cheddar” by using a mozzarella base and then misting on cheddar flavour and orange food colouring. Leprino Foods’ production rose sixteen-fold, to 2 million pounds of cheese a week.

Just as his timing ahead of America’s pizza boom proved lucky, so did his location in the centre of the country. In the 1970s, Wisconsin and New York were producing most of the country’s milk, but California’s nascent dairy industry often priced milk lower. Leprino had the foresight to engage in some arbitrage, locking California dairy farmers into multi-decade contracts at rates that were often above-market locally but below-market nationally. Over the next two decades, Leprino Foods also signed sweetheart deals with co-ops that eventually became the Dairy Farmers of America, securing a lasting milk supply with the country’s largest dairy co-op the company also purchased and renovated some of the older dairy plants, cutting off the options for competitors who wanted to process milk. As Jerry Graf, a former cheese buyer for Pizza Hut, notes, “Jim was always one step ahead of the game.”

Leprino’s most important innovation, ultimately, was marrying science and sales—a combination that met the needs of the four biggest US pizza chains during a period when they were growing exponentially, launching one of the greatest turf wars in the history of American food.

The first key was something called “Quality Locked Cheese”—shredded and individually frozen portions—which Leprino introduced in 1986. Leprino’s competitors, still mostly run by Italian-Americans with strong immigrant roots, sniffed. “They didn’t believe that was what should go on top of their grandmother’s pizza recipe,” says Ed Zimmerman, a 30-year pizza-industry veteran. But the franchise-friendly process quickly became the industry standard, both for consistency and scalability. With a patent in place, Leprino made himself indispensable. Graf left Pizza Hut, which was still growing, for Domino’s and brought Leprino’s business with him, as that chain surged from 200 outlets in 1978 to 5,000 in 1989. Meanwhile, Little Caesars, with more than 3,000 stores, was growing at 25 percent a year with its deal of “Two great pizzas, one low price”. And by 1991, Leprino had become the exclusive supplier for Papa John’s, which launched in 1985.

Leprino was able to grow with them all by putting them in silos, granting each company its own specs and then troubleshooting as necessary. “We treat every customer like our only customer,” says Mike Durkin, a former Pepsi executive who came on six years ago to run day-to-day operations as president of Leprino Foods. Domino’s agreed to an exclusive relationship in 1996—the contract was just one page. “It was more of a handshake than it was anything else,” recalls Michael Soignet, a former vice president of supply chain at Domino’s.

When Pizza Hut began using a hotter conveyor oven, Leprino Foods changed the formula so the cheese wouldn’t burn at higher temperatures. As delivery-focussed Domino’s expanded, Leprino’s head cheese maker, Lester Kielsmeier, manipulated the product so that it retained its fresh-out-of-the-oven look and taste longer. When Papa John’s insisted it wanted cheese without fillers—eschewing a new Leprino product that contained some—the big cheese didn’t take it well. “His reflected sense of self is his patents, his business,” Papa John’s billionaire founder John Schnatter says of Jim Leprino. “That really means a lot to him. When I said I didn’t like it, he took it personally.” Within two months, Leprino switched Papa John’s back to the previous blend. “Jim came at me and said, ‘It’s going to cost you three more cents a pound’.”

Price has long been Leprino’s biggest advantage, and a large one since cheese accounts for about 40 percent of a pizza’s cost. Leprino’s scale begat better prices, which begat more scale. And that scale also led to cost-saving breakthroughs that Leprino’s competitors could neither catch up with technologically nor fight in patent court. “They are a biotech company that is wrapped inside a food business,” Zimmerman says.

For example, in the 1990s, Kielsmeier realised that just as the cheese changed when ingredients were sprayed on at the end, certain additives used early in the process could affect how cheese melts—from how big and how brown the bubbles get to how many are on the top of the pie. On the manufacturing side, Kielsmeier cut down the cheese’s ageing period from 14 days to just four hours, which multiplied the company’s production capabilities while cutting costs significantly.

“I would tell people, ‘Lester is the man that made me rich’,” Leprino says. Notably, though, Leprino never gave Kielsmeier any equity. While Leprino got rich, Kielsmeier—who came to work every day right until his death at 95 in 2012—would have to content himself with being very well paid.

For James Leprino, the perks of being a billionaire are relatively muted. Yes, the company owns three private planes—a Gulfstream G450, a Bombardier jet and a small 1980 commuter plane—and his house in Denver’s affluent Indian Hills suburb has 11 bedrooms, to go with an 8,000-square-foot vacation home in Scottsdale, Arizona. But he’s more likely to pick up a hammer than call a repairman: Leprino, who has been known to operate a forklift at the factory, has also personally bulldozed trees around his Colorado home. A devout Catholic, he goes to church every Sunday and donates to charity anonymously. And the immigrant’s son has no intention to retire, ever. “My success is a fairy tale,” he says.

Leprino’s succession plan is simple: He’ll split ownership between his two daughters, Terry, 57, and Gina, 55, who have been on the board for years but won’t take day-to-day roles. And for now he’ll continue to ensure that Leprino cheese is on as many American pizzas as possible—as well as Asian and European ones (Leprino has a joint venture with the UK’s Glanbia Cheese).

America’s fifth-largest pizza chain, the take-and-bake Papa Murphy’s, remains in his sights. Co-founder Robert Graham says Leprino visited him at least three times to try to get the company to sign on, selling the technology above all else. “It didn’t perform well for our pizza, which is cooked in a home oven,” Graham says. “Because of the moisture content, you could see the sauce under the cheese. It evaporated.” Yet Leprino executives continue to press.

And while Little Caesars uses other vendors—industry insiders say Leprino isn’t exclusive with Little Caesars, in part because the chain’s blend uses Muenster cheese, too—Leprino President Mike Durkin predicts that Little Caesars will eventually succumb. “Would we want more? Probably the answer is yes, and it’ll come at some point,” he says.

Meanwhile, Leprino will pursue new markets. It has invested $600 million in a factory in Greeley, Colorado, that specialises in “ribbon cheese”—bulky 2.5-pound blocks that are popular among frozen-pizza companies. It’s also created an in-house “innovation studio”, designed to ride the coattails of food trends. One creation, Bacio (“kiss” in Italian), is catering to artisanal-pizza-makers by offering mozzarella with a kiss of buffalo milk. It’s Leprino Foods’ most expensive cheese—and its fastest-growing.

Leprino is also rolling out the company’s first direct-to-consumer product, a whey protein powder called Ascent, which will have a dedicated wing at the Greeley facility. While Leprino still produces whey protein as a byproduct of making cheese for its clients, Ascent is filtered straight from raw milk to protect key proteins and vitamins that help aid muscle recovery. Leprino hopes that will be an edge in the $6.6 billion-and-growing US protein market.

There is plenty of history to remind Ascent’s team of their roots. Ascent’s space sits atop the original cheese factory’s loading dock and warehouse.

“I remember the first day that we had this set up,” says Mike Arnold, who is overseeing Ascent’s launch. “Jim Leprino walked in here and was like, ‘Ah, this reminds me of the old days’.” A new, fractured market, primed to be dominated.

First Published: Jun 23, 2017, 06:00

Subscribe Now