The Greatest Deal of all Time

Billionaire financier Len Blavatnik's bet on LyondellBasell has netted him a personal profit of nearly $8 billion. He says there's more to come

Last November, Apollo Global Management, the powerful buyout shop run by billionaires Leon Black, Marc Rowan and Joshua Harris, finished cashing out of arguably the greatest private equity deal of all time.

As they furiously sold billions of dollars of shares in LyondellBasell, a chemical maker, in several batches, they had every reason to think they were doing the right thing. By any metric it was a monstrous score. Since 2008 the firm had turned a $2 billion investment in the company, a plastics manufacturer and petroleum refiner based in Rotterdam with its main executive offices in Houston, into $12 billion, a six-fold return on investment that juiced the results of its biggest fund to a net internal rate of return of 30 percent. It was an astonishing result, especially in post-crash Wall Street, landing Apollo atop the lucrative private equity world and helping to launch an initial public offering of the firm, which is now valued at $10.5 billion. Harris earned $397 million from his work at Apollo last year alone Black made $546 million.

But even as Apollo’s billionaires were exiting from LyondellBasell, another billionaire investor was continuing to double down. In 2013, Len Blavatnik spent $575 million purchasing 8.5 million of Apollo’s LyondellBasell shares, an unparalleled bet on an investment that had already helped make him one of the richest men in the world, and one that had many scratching their heads at the time.

“It’s an easy argument against it: If Apollo is selling, why are you buying?” Blavatnik tells Forbes in a rare interview. “Before every one of my additional purchases of stock in LyondellBasell, some people around me told me it was a mistake and that I should sell instead of buying more.”

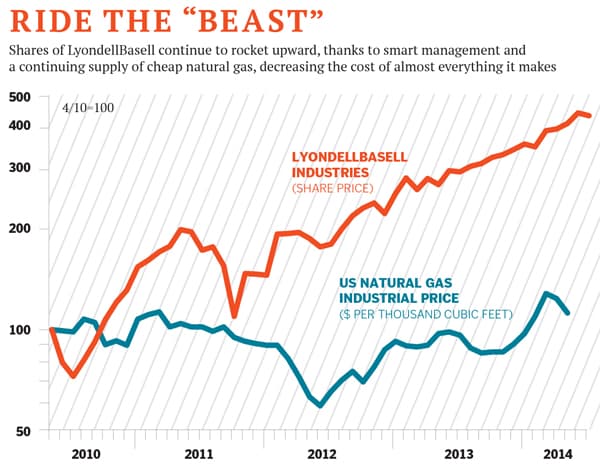

But so far Blavatnik has been right— seriously right. Shares of LyondellBasell have soared by more than 50 percent since he bought his last block of stock from Apollo.

In the history of Wall Street, there haven’t been too many money-making machines quite like LyondellBasell, which has seen its shares return 500 percent since it emerged from bankruptcy four years ago. And that’s been especially lucrative for Blavatnik, 57, who cobbled the company together, saw it fail and plunge into bankruptcy court, and then doubled down on the same assets, personally investing another $2.37 billion in LyondellBasell the second time around.

His investment is now worth more than $10 billion, generating $8 billion in mostly unrealised personal profits. As it stands, Forbes believes it’s the biggest individual score from a single deal, ever. While Blavatnik usually makes headlines these days for his media holdings, those parts of his portfolio are a sideshow compared to the LyondellBasell redemption that has pushed his net worth above $20 billion—making him the world’s 33rd-richest man.

“It is a historic transaction,” says Mark Epley, MD in Nomura’s private equity banking unit. Says Stuart Gilson, a Harvard Business School finance professor who has studied LyondellBasell’s restructuring: “It’s outstanding given the return, but recalling what we were all feeling in 2008—it was the end of the world—makes the outcome even more remarkable given the enormous risk.”

Blavatnik, who owns 16 percent of LyondellBasell through his Access Industries, thinks there’s still more room to run, wagering that LyondellBasell’s stock will continue to rise. “So far I feel vindicated and proud of my investment decisions,” he says. “The question is whether the luck will continue.”

When Len Blavatnik was first handed an investor memorandum for Dutch chemicals company Basell, it had the number 64 on the cover, prompting one of Blavatnik’s associates to caution him about jumping in. Why bid for a company that 63 other players were already considering? Blavatnik waved him off—he wanted to create a global chemicals empire, and this was his way in. A Ukrainian-born American citizen who grew up in Russia and immigrated to the US in 1978 at the age of 21, he later got his MBA at Harvard. Blavatnik made his first fortune with a former classmate in Russia, Viktor Vekselberg, in oil and aluminum deals during the anything-goes post-Soviet days.

Blavatnik’s biggest scores in Russia were oil company TNK-BP, a joint venture with British Petroleum that was eventually bought by Rosneft for $55 billion, and Sual, an aluminum producer that merged with the larger Rusal. Chemical companies that had nothing to do with Russia would be his next big thing. He paid full price, putting down $1.1 billion to purchase Basell in a $5 billion leveraged buyout in 2005. Then he tried, and failed, to buy other chemical companies, including Huntsman International.

In 2007 Blavatnik decided to buy Lyondell, a Houston-based company—not particularly well run—that produced commodity chemicals used in making plastics and that also had refining assets. Blavatnik had been stalking Lyondell, buying up the right to purchase 8 percent. When he decided in July 2007 to use Basell to buy up a controlling stake in the company at $48 a share, a 45 percent premium to the market price, Blavatnik’s associates got nervous. Alan Bigman, a trusted lieutenant who’d been working for Blavatnik for a decade, woke up at 4.30 one July morning, unsettled by the deal.

“I know you’ve already made up your mind,” Bigman wrote to Blavatnik, according to a court document. “But I am uncomfortable with the valuation.” Blavatnik waved him off and did the same when Philip Kassin, another colleague who also sat on Basell’s board, expressed his own worries. Ultimately, Blavatnik has told Forbes, employees can voice their opinions, but he is “risking my money, not their money”.

Basell bought Lyondell in a $20 billion leveraged buyout in December 2007 to create LyondellBasell, the world’s third-biggest independent chemicals company. The timing couldn’t have been worse. Within months, the financial crisis hit and the deal looked like a debacle. Weighed down by more than $20 billion in debt, LyondellBasell hit the wall as the economy crumbled. Chemical orders stopped, a huge crane collapsed in an accident at its Houston refinery that killed four employees, and Hurricane Ike shut down its plants in Texas. Some 2,500 employees, 15 percent of its workforce, were laid off at the end of 2008. In 2009, Blavatnik pushed LyondellBasell into bankruptcy. It was a humiliating moment for him. “Filing for Chapter 11 is an experience I would never want to repeat it was really a dark moment,” he has said of that time.

It was also his biggest-ever financial loss. How much he lost has been a subject of fierce litigation by LyondellBasell creditors, who went after Blavatnik in a lawsuit that continues to this day. At minimum, Blavatnik was out $1.2 billion. But despite the reversals, Blavatnik believed in the assets and potential earnings power of a company he felt had simply been hit by a perfect storm.

He wasn’t the only billionaire with an appetite for chemicals. Apollo had also been trolling the industry, buying and owning chemical assets like Hexion Specialty Chemicals and Momentive Performance Materials that had been similarly battered by the financial crisis, sinking Apollo’s performance. Yet, like Blavatnik, Harris, Black and Rowan knew the industry and decided to keep investing. Before LyondellBasell headed to bankruptcy court, Harris bought LyondellBasell term loans from a reeling Citigroup at a discount and kept buying bank debt for as low as 20 cents on the dollar, as the financial crisis raged and those loans plunged in value. Harris knew some people on Wall Street thought he had lost it, but Apollo’s analysis determined that the most secured LyondellBasell debt would perform well absent a complete global economic collapse.“Every day we would buy Lyondell as prices fell. We had conviction, and we were buying super cheaply,” Harris tells Forbes. “We were able to pair our deep industry expertise in chemicals with a highly complex distressed process so it highlighted what we are good at in terms of distress for control.” It was a daring $2 billion investment that gave Harris an opportunity to convert his debt into a big equity stake in LyondellBasell in bankruptcy court. That meant working with Blavatnik. Harris and Blavatnik are friends who still get together socially and whose wives know each other. Still, a minor skirmish broke out between them over who would run the “debtor-in- possession” bankruptcy financing— and in turn have more control over the company. In the end Harris won out, leading an $8 billion bankruptcy financing that included an innovative roll-up feature that allowed Apollo to move some of its debt higher in the capital structure. Harris and two other Apollo representatives jumped on LyondellBasell’s board, and they worked closely with Blavatnik and his team on the restructuring. “Overall, we had a very good working relationship with Apollo,” says Blavatnik. “Sometimes it was tense because we had somewhat different interests in the beginning.”

The bankruptcy wiped out Blavatnik’s stake in the company, but he found ways to rebuild equity in LyondellBasell. He also kept his new key advisor, Stephen Cooper, who had guided Enron through bankruptcy as CEO, on the board.

In bankruptcy court, LyondellBasell shed the weight that brought it down—bad contracts, high-cost assets, expensive plants in Texas and Germany. It reduced its debt load to $2.5 billion, slashing annual interest expenses by $1.7 billion. The company added as its CEO Jim Gallogly, who had headed Chevron Phillips Chemical Co. Gallogly got 1.8 million restricted shares and options to purchase 5.6 million shares for $17.61 apiece to run the floundering company. “It was hard to convince Jim, and it took us some time,” says Blavatnik. “We offered a very attractive package.” In 2010, LyondellBasell emerged from bankruptcy court valued at $15 billion. That number was about to soar.

The revolution that changed everything for Blavatnik, Apollo and LyondellBasell originated in the thin fissures of shale rock filled with oil and natural gas reserves throughout the US. Throughout the last decade, drillers pioneered new techniques of exploiting rock formations with hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling to draw out the petrochemicals trapped within. As a result, the US became one of the world’s largest sources of cheap natural gas almost overnight, with prices falling from highs of $13 per million British thermal units to a $3 to $4 range today. This dramatic drop in prices proved a huge boon to dozens of industries, none more so than the chemical business—and few more than LyondellBasell.

LyondellBasell is a top producer of ethylene, which it upgrades into the plastic known as polyethylene, used in everything from food packaging to trash bags and hard hats. The company operates six facilities (known as “crackers”) to produce ethylene in the US and four in Europe. Profits from ethylene and its derivative chemicals and coproducts are the core of LyondellBasell’s earnings.

Ethane, refined from natural gas, and naphtha, a crude oil derivative, are the prime raw materials used to produce ethylene. Starting in 2007, US drillers were finding natural gas everywhere. By 2012, the price of ethane had fallen from 90 cents per gallon to 30 cents, giving US chemical producers a huge advantage over foreign competitors in Europe and Asia that are dependent on pricey oil-based naphtha as a feedstock. The gap between the two supercharged LyondellBasell’s profitability.

LyondellBasell’s decades-old crackers in Clinton, Iowa, and Morris, Illinois, for example, are the only ones in the Midwest—and are situated near natural gas liquid pipelines and a hub in Kansas, home of some of the cheapest ethane in America. Almost overnight they were transformed, churning out profit margins of 32 cents per pound compared to European naphtha-based ethylene, which is barely even profitable. “It’s improbable that anyone could have foreseen the full impact of the shale revolution,” says Blavatnik. “But Jim had some experience and insight through his work at ConocoPhillips that I think helped.”

Gallogly, 61, a lawyer by training who was born on Canada’s Newfoundland island, cut $1 billion of annual fixed costs and guided the company to swiftly take advantage of the shale gas boom, converting the company’s US processing facilities so that 90 percent of the time they can run on cheap natural gas-based feedstock. Instead of spending huge amounts of money and time building new crackers, he incrementally expanded capacity at his existing US plants. That shortened construction time and allowed the company to quickly benefit from the ethane advantage, adding capacity while others waited for new permits. Instead of it taking six years for new plants to come online, it has taken just two years to add capacity. “Perhaps you have heard the expression,” Gallogly likes to say, “&thinsp‘The early bird gets the worm’?”

In all, Gallogly has spent just $3.7 billion over the last three years on capital expenditures. He spent $510 million to expand capacity of a steam cracker in La Porte, Texas, to be able to process 800 million more pounds of ethylene from ethane, a project that will finish this year. He spent another $200 million to increase the ethane-processing capability at the company’s cracker in Channelview, Texas. Those crackers in the Midwest? For just $30 million, Gallogly added 100 million pounds of ethylene and polyethylene capacity, worth an estimated $30 million in operating profits to the company. LyondellBasell has gone from posting losses in 2009 to profits of $3.9 billion on revenues of $44 billion last year. (Gallogly’s shares of LyondellBasell are now worth $380 million.)

Just as importantly for Blavatnik, Apollo and other shareholders, Lyon- dellBasell has been a cash machine. In the past three years, the company returned $8.4 billion to shareholders via share repurchases and dividends. It’s “a beast”, says Deutsche Bank analyst David Begleiter. “They are the poster child for the renaissance of the US chemical industry.”Other bigshots on Wall Street have taken notice. Billionaire hedge fund manager Dan Loeb used more than half of his first-quarter letter to his investors wondering why Dow Chemical Co—where returns have trailed LyondellBasell significantly over the last three years—wasn’t more like its rival. Loeb’s Third Point hedge fund has taken a position in Dow, and the activist investor made it clear that he would push Dow to follow LyondellBasell’s lead. “Underearning is clear when one compares Dow to its North American petchem peer, LyondellBasell,” Loeb wrote in May.

Not everyone is convinced the party will last, but so far Blavatnik continues to have made the best bet. The investment firms of some billionaire investors—including Antony Ressler, David Einhorn and James Dinan—held stakes in LyondellBasell after it emerged from bankruptcy and sold them in the early innings of its rally. Harris and Apollo held on much longer, selling their LyondellBasell shares at an average price of $62.65 a share. Still, in July, LyondellBasell started trading above $100. The feeling at Apollo was that the investment was unlikely to continue providing the kind of high returns private equity investors expect. Apollo, mindful of the cyclical nature of the chemical industry, also simply thought it was time to monetise one of the greatest deals ever. “As an institutional fund we have to make private equity returns,” says Harris. “So in our view it was time to monetise.”

Of course, unlike Blavatnik, who invests on his own dime, Harris’s Apollo needs to return money to outside investors. In fact, as Apollo was selling its LyondellBasell stake, it was raising $18.4 billion for Apollo Fund VIII, the most ever for the firm—and the biggest new private equity fund raised by far since the financial crisis. LyondellBasell certainly helped, making up 15 percent of the profits of the wildly successful Apollo Fund VII.

Now Harris and Apollo are making bets that natural gas prices will increase, essentially going against Blavatnik’s take on the market. In June Apollo announced it was buying natural gas properties from Encana for $2 billion in a straight- up play on rising natural gas prices. Apollo has also been wagering on Energy Future Holdings, a leveraged buyout bankruptcy that is actually bigger than LyondellBasell, working to take control of Energy Future Holdings’ unregulated unit, which would benefit if natural gas prices rise because the company produces electricity using coal and uranium while most electricity in Texas is generated using natural gas.

Blavatnik shrugs off worries about rising gas prices and continues to believe fervently that changes to the energy and chemical markets are near permanent, and abundant low-cost ethane will continue to fuel LyondellBasell. “The shale revolution is continuing,” he says. “And we see the competitive advantage staying for some time.”

First Published: Sep 12, 2014, 07:16

Subscribe Now