Why Mazda believes the future is the past

The entire auto industry is betting on self-driving cars—except Mazda's Masamichi Kogai, who believes lots of people love to get behind the wheel

Squeezing the accelerator on the Mazda MX-5 Miata as it exits a curve on a twisty back road in Michigan, you can’t help but smile. In the rearview mirror you can see a whoosh of dead leaves rising in your wake, dancing to the hum of the exhaust coming from the car’s high-revving, four-cylinder engine. Mazda’s $25,000, 155 HP roadster is not the most powerful car on the planet—far from it. But with the top down and the sun warming your neck on an unseasonably mild December day, you just want to keep driving forever. It’s that much fun.

Mercedes-Benz, Cadillac, Volvo—not to mention Google, Tesla and, rumour has it, Apple—are all racing to relieve drivers of that fun. Within five years, most automakers say, they’ll offer highly automated cars that can handle stop-and-go traffic and freeway speeds without any driver input. In ten years drivers will be able to work or even take a nap during their commute. Volvo just unveiled the Time Machine, a futuristic cockpit with a 25-inch flat-screen that rotates out of the dashboard as the steering wheel retreats and the driver reclines. Google is developing self-driving cars that don’t even come with a steering wheel or gas pedal.

This is the future, asserts Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk. “Any cars that are being made that don’t have full autonomy will have negative value,” he predicted in a November conference call with Wall Street analysts. “It will be like owning a horse. You’re really owning it for sentimental reasons.”

Not everyone thinks so. “It’s not just getting from point A to point B,” says Mazda’s soft-spoken CEO, Masamichi Kogai, who heads up perhaps the only major automaker that is not working on autonomous cars. “Our mission is to provide the essence of driving pleasure.

“The car for me is like being home,” he continues. “As soon as I get inside the car, no one outside can bother me. I might go to a lake or to the mountains. I don’t know where I am going until I get there.”

Kogai has a very clear road map, however, when it comes to leading the once struggling Mazda into the future. The company tried keeping up with larger Japanese rivals like Toyota and Nissan and nearly wound up bankrupt, losing billions in the mid-1990s. Ford Motor, which had owned a small stake in Mazda since 1979, soon became its largest shareholder, effectively controlling the company with a 33 percent stake. But by 2008, in the throes of the financial crisis, Ford slashed its stake to 14 percent, then dumped the rest starting in 2010. Cast off in a sea of red ink, Mazda went into a tailspin, losing nearly $3 billion from 2009 to 2012.

Mazda was forced to rethink every aspect of its business, from the way its cars are designed and engineered to the way they are assembled. Kogai was in the thick of it, first as head of manufacturing, then as chief executive since 2013. He overhauled Mazda’s manufacturing footprint, ending production in Michigan while opening a new plant in lower-cost Mexico and setting up joint manufacturing ventures in Russia and Vietnam.

Cost-cutting alone wouldn’t solve Mazda’s problems. It had to figure out how to be as agile as its cars.

Instead of designing cars one at a time and leaving it up to the manufacturing team to figure out how to produce them, Mazda pulled everyone together—designers, engineers, suppliers, purchasing staff and production experts—and began plotting its entire lineup five to ten years out.Their most difficult challenge was figuring out how to make fun-to-drive Mazdas that would meet tougher fuel-economy standards without an R&D budget for hybrid or electric cars.

Mazda turned that weakness into a strength, defying conventional thinking by theorising it could hit the targets with regular gasoline engines—albeit radically redesigned ones. It developed a new engine from the inside out, boosting the combustion efficiency to levels no other automaker would dare try because of the associated ‘engine knocking’. But since Mazda was starting with a clean sheet, it redesigned the exhaust system, chassis and body to offset such effects and achieve the desired engine performance. The soup-to-nuts approach resulted in a 15 percent improvement in fuel efficiency over previous engines and was quickly incorporated in models like the Mazda CX-5 crossover and the Mazda3 and Mazda6 sedans. The last two get close to 40 miles per gallon (the bigger SUV gets a solid 33).

To pay for it, Mazda issued $2.7 billion in a stock and debt offering in 2012. It was a gigantic bet for a small company trying to stay competitive with larger global players.

But it worked. After the catastrophe of its divorce from Ford, Mazda has been profitable for the last three years. In the fiscal year ended March 31, 2015, net income was $1.3 billion, on revenues of $25 billion. Global vehicle sales are up 12 percent since 2012, and Mazda’s Ebitda margin has improved to almost 9 percent, better than Ford’s 7.9 percent but still lagging the industry average of 11 percent. Wall Street isn’t a believer. Mazda shares were down 15.7 percent in 2015 (through mid-December), versus 3.4 percent for the industry as a whole.

Mazda attributes its resilience to its history, which is inextricably linked to its hometown of Hiroshima. When America dropped the first atomic bomb on the city in August 1945, Mazda, then known as Toyo Kogyo Co. Ltd., made three-wheel trucks and military hardware. While most of the city was flattened, Toyo Kogyo was spared by a quirk of topography: A hill between the blast site and the factory diverted the inferno up and over its operations. Within four months Mazda was back in business.

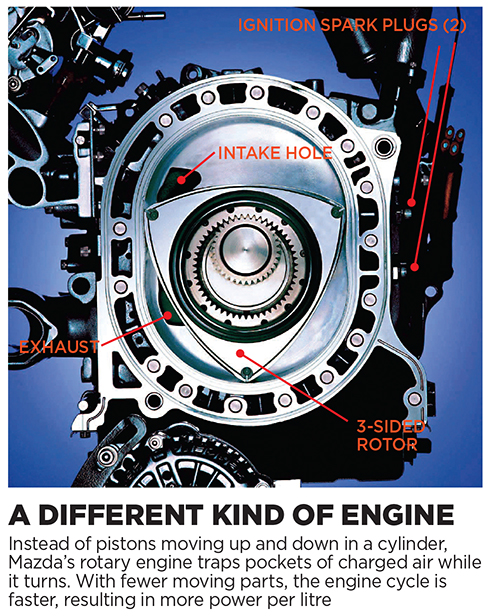

By the early 1960s, Mazda was making cars. But so were a lot of other Japanese companies. When the government wanted to consolidate the industry behind a handful of strong companies, Mazda’s then president, Tsuneji Matsuda, saw the writing on the wall. To preserve Mazda’s independence, he licensed a promising technology for a rotary engine from German scientist Felix Wankel in 1961. Elegantly simple but difficult to make well, the rotary engine became Mazda’s obsession for the next half-century. In 1967 the company introduced the world’s first rotary sports car, the Cosmo, followed by the rotary-powered RX-7 in the late ’70s, ’80s and ’90s and the RX-8 in the 2000s. A win at 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1991 sealed Mazda’s cult following.

There was an outcry in 2011, when Mazda stopped production of the slow-selling RX-8, but now Kogai has given loyalists reason for hope. At the Tokyo Motor Show last November he unveiled the RX-Vision, a sports car concept that had Mazda lovers drooling. A smiling Kogai was coy about whether Mazda would build it: “The only engine we can think of in that car is a rotary engine.” There will be plenty of drivers lining up if it happens.

First Published: Feb 15, 2016, 06:41

Subscribe Now