Pratap Bhanu Mehta: When Business Bats Against Itself

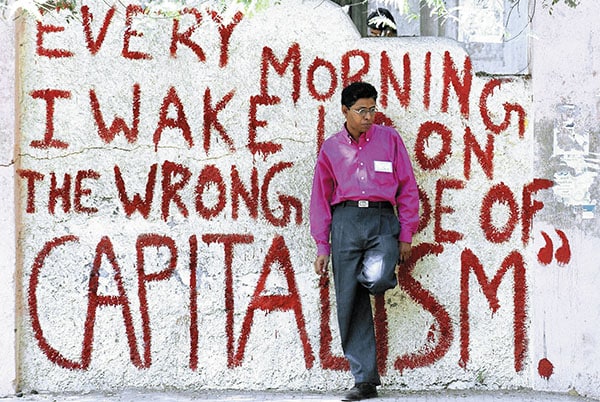

Indian capitalism is the single biggest obstacle to further economic reform. It still inhabits a world of deals rather than rules

Pratap Bhanu Mehta

Profile: Pratap Bhanu Mehta is president of New Delhi-based think tank Centre for Policy Research, and is a member of the National Security Advisory Board and the World Economic Forum’s Global Governance Council. His areas of research include political economy, constitutional law, governance and international affairs.

There is widespread consensus that India does not have a political culture propitious for business freedom. It fares poorly across all global indicators that measure ease of doing business. The daily uncertainty, arbitrariness, obstruction and degrading humiliation that anyone trying to honestly do business in India faces is living proof of an institutionalised hostility to business. But contrary to widespread perception, the main source of this hostility is not just the state. The evolution of Indian capitalism itself is in large measure responsible for it. The bourgeoisie of this country has not come of age when it complains it squeals more like a sulking child than a confident class. Instead, it needs to ask hard questions about why India is less pro-business.

When the history of India’s reforms is written, scholars will blame their slow pace on many factors: The vested interests of the state, the inability of politics to take economic arguments seriously, the anxieties of the middle classes that continue to depend on the state, the complexities of policy in an agrarian society, the wages of populism and the inherited baggage of socialist illusions. But one influence that will stand out is that of India’s capitalist classes. For it is now palpably clear that Indian capitalism, despite the developments of the 1990s, is the biggest obstacle to further economic reform. Individual capitalists are undermining the long-term prospects of a free economy for their own immediate short-term gain.

One of the principle objectives of reform is to reduce the discretionary power of the state so that the ground rules regulating economic transactions are open, clear, predictable, competitive and fair. Licences and production controls were only one aspect of this discretionary power tax exemptions and a plethora of other regulations are its other facets. But apart from production, the government has to regulate industry on labour issues, environmental concerns, land permission and so forth. It is wishful thinking to suppose that you can have capitalism that is not thus controlled. The question is whether the regulation is sensible and predictable. The government often has its own interests in an absurdly regulated or an over-regulated but under-governed system. But Indian capital, rather than collectively fighting for rational regulation, spends its energies extracting its own form of rent from this misregulation. Industry uses inordinate resources in keeping its exemptions intact or manipulating rules to its advantage. While rational from the point of view of particular entrepreneurs, cumulatively, the politics of exemption-seeking impedes reforms. It reinforces the view that the function of the state is not to set fair rules, but to dole out selective benefits. Indian industry still inhabits a world of deals rather than rules.

There are too many examples of this. Rather than lobbying for sensible environmental regulation, industry dissimulates by attacking the idea of environment itself or by quietly seeking exemptions. India’s infrastructure is at a standstill not just because the government is paralysed. It is also because many of the infrastructure players were more comfortable with a deal-based world: Their business model was premised on the expectation of inordinate returns, ability to renegotiate contracts and so on. Big business saw its interests as separate from business in general. They were allowed options to exit and hedge against all risks they were given captive power, easy credit, cover against the exchange rate, etc. SEZs were an exceptional land grab raj in disguise. They could fight the state on everything. But it is really the small entrepreneur who suffered the brunt of the state’s anti-business bias. What we call reform has largely been pro-big business as opposed to business.

That the politics of exemption-seeking is widespread is not a big surprise. What is less remarked upon is the deleterious effect this has on the legitimacy of capital. Many have long argued that Indian capital’s idea of entrepreneurship consists not of making innovative products, but fleecing the state. This perception continues to be valid even after a decade of liberalisation. The net result is that the wider population does not see an attack on market forces as an attack on freedom, entrepreneurship and innovation. Rather, it sees it as an attack on graft. It looks at Indian capitalism as the creation of a corrupt system rather than, as industry would like to present it, the victim. The conduct of Indian capital is the biggest obstacle to the legitimacy of capitalism.

Capitalism survived in most places, in part, by socially legitimising itself. It was able to, for all its vicious faults, present itself as a perpetual innovation machine introducing new products and efficiencies, a source of expanding revenues that the state could then use for other social purposes, a mine of new knowledge that expanded the frontiers of technology.

In India, for a variety of historical reasons, capital started with low social legitimacy. But in the half-century since independence, it has not done much to enhance its credibility. At one level, it can be quite efficient. But at another, it has not excited romance in any sense. It is, some exceptions apart, not known for great innovation in manufacturing. It has not expanded the technology frontiers of production. It is not at the vanguard of design. You could argue that this is because its hands were tied by the hostility to business. But the fact is it has done nothing to get people excited.

Indian capital has been narrowly short-sighted. It never understood that good capitalism needs a good state. Instead, it tried to hitch its wagon to an ill-thought sensibility—“public bad, private good”. It was so simple-minded and general in its critique of the state that it threw the baby out with the bath water. By delegitimising a proper idea of the public, it denuded the very foundation needed to sustain it. Someone once remarked that the trick in capitalism is to make one generation’s bad money serve another generation’s good. It has to take off the rough edges. In the United States, this took on the form of a massive investment in creating ‘public’ goods— universities, patronage of arts and so forth. It was capital acknowledging, perhaps hypocritically, that it needed to transcend a narrow and pinched-up instrumentalism.

Indian capital’s face, with a few exceptions, is narrowly instrumentalist. You cannot have liberal economics without creating a massive infrastructure of liberal culture, in the true meaning of the term. The economist Adam Smith also surmised that capital’s power is, in part, aesthetic. It is its ability to create a veneer of order and aestheticism that helps it capture the imagination. If the public sense of space and architecture has been a monstrosity, there has been nothing in private capital to inspire confidence. It too has bound the imagination by its penny pinching.

Much is made of the fact that Indian capital is increasingly delivering many services. But this is a double-edged sword. While these might be a palliative to failing public institutions, they are not sources of great support for private business. If anything, the experience of private institutions, while acknowledged as a necessity by many, is also a source of resentment.

As if this was not enough, capitalism has come to be associated with the most sordid kind of politics. Older capitalists had the good sense to manipulate politics but not become politicians. Now the lines are blurred. Indian capital has a sense that it has too many skeletons in its closet and operates with that sense of vulnerability. This has made it intellectually servile—a cowering bourgeoisie tailing politicians rather than an independent class articulating powerful ideas.

As economic reform slows down, as the rate of growth decelerates and inflation creeps up, don’t be surprised if the very class that made the country rich in the ’90s becomes the target of a backlash. After all, if most people are convinced that capital’s success in India is not due to its virtues but is a result of its vices, few will come to its defence. If the politics of capital contributes to fiscal and market distortions, rather than correcting them, the economy will have little future.

Capitalism has this in common with democracy: Under both systems, you can fool some people all the time, all the people for some of the time but not all the people for all of the time. As Smith put it, capitalists are the biggest obstacle to capitalism.

First Published: Aug 14, 2013, 06:49

Subscribe Now