Mother and Child

Artists have experimented with the subject over centuries, creating images that range from the idyllic to the maudlin

It is one of the most represented subjects, almost a rite of passage for any artist, and it unleashes a gamut of emotions for both the creator as well as the viewer. It also remains extremely challenging, perhaps because there are so many styles and expressions to compare with, as our selection of works on the Mother and Child theme by Indian artists for this issue uncovers.

TRADITION BOUND

Anonymous (late 19th century) Early Bengal Oil on canvas

Indian art’s tryst with modernism occurred in Bengal where visiting colonial artists brought with them the freshness and excitement of the realistic way of painting on a large scale, using the more glamorous medium of oil and canvas. This was an opportunity to exploit the Western practice of art within the Indian context. Artists who had, till then, operated out of ateliers started to practise in the manner of these Western artists, thereby creating a new language of art. For the first time, the Indian idiom borrowed ideas such as perspective or depth and chiaroscuro or a source of light. A school of paintings known as Dutch Bengal Oils (and, later, simply Bengal Oils) became rapidly popular. Their mythological themes were borrowed from miniatures, as were the clothes and backgrounds, but the artists often grappled with the dilemmas of perspective—which in this soft modelling of Yashodha and Krishna can be noticed in the oddly sized body of the infant and the elongated and ballooning skirt of the mother. But the soft tones and decorative detailing, a highlight of these paintings, remains unsurpassed in Indian art. RHYTHMICALLY LINKED

RHYTHMICALLY LINKED

Prodosh Das Gupta (1912-91)

Bronze

Unfettered by local sculptural traditions, Prodosh Das Gupta drew inspiration from the West, particularly London and Paris where he studied, and the works of Rodin and Henry Moore. He was drawn to the inherent rhythm in sculptural art, and came to be recognised for his ‘instant’ sculptures, figures he moulded while playing with lumps of clay, with no preconceived notion of the result. This is apparent in the sculpture of a mother playing with her little charge. The modulation seems to have been arrived at by letting the forms emerge from the material with haste. The forms are linked by the medium and the cadence the artist has contrived to create. Deeply absorbed in their play, their individual identities remain firmly etched, despite one being a part of the other. The mother’s dominant figure does not overpower the child’s, even though she looms over it. What appears is a deep understanding between the two. CANDID MOMENTS

CANDID MOMENTS

Prahlad Karmakar (1900-46)

Oil on jute (c. 1935)

Reminiscent of works by dutch artists, this oil is representative of the evolving style in Bengal where academic realism was being taught at the Government College of Art and Craft in Calcutta. A trained artist, Prahlad Karmakar paints a portrait of his wife Sahi Sundari and their son Prokash (who would grow up to be a well-known artist). The two have been depicted in a moment of deep intimacy, unaware of the painter. The candid portrait shows them taking a siesta, probably in a darkened room, after the baby’s feed. The artist has painted them in close-up, eliminating all that is exigent. In that claustrophobic embrace, some of the romanticism of the genre is captured, but there is also a sense of candour, as if, in their innocence, they lay themselves open to investigation. The closeness of their bodies and the dim lighting serves to remind us of the role a mother plays in caring for her child against odds.

UNIVERSAL MOTHER

MF Husain (1913-2011)

Oil on canvas

Bollywood’s Indian mother could well be the cliché that Husain lived with all his life, her absence a void in his life that he filled with his ‘portraits’ of Mother Teresa. Even though he had no memory of his mother, he “remembered” her as a Maharashtrian woman in a nine-yard saree with ghungroos on her feet—and cast Madhuri Dixit in that mould in his film Gaja Gamini. But he found solace in Mother Teresa, whom he iconicised in the form of a white saree with a blue border. That image recurred for several decades in his work and became symbolic of the Mother as well as motherhood. He did not depict her face because in it he sought his own mother’s face, and wanted to offer similar succour to others. Nor did he paint Mother Teresa as a solitary figure but always with children clinging to the folds of her saree to seek comfort in her lap. In doing so, he was establishing her universal humanity and motherhood. MADONNA MAKEOVER

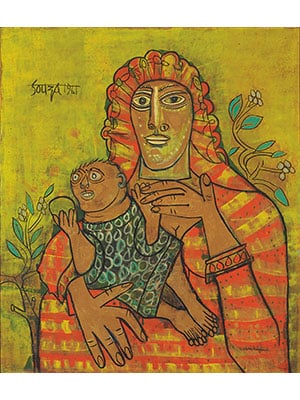

MADONNA MAKEOVER

FN Souza (1924-2002)

Oil on canvas (1961)

FN Souza seemed to have spent the bulk of his career painting misogynistic images of women and furious ones of the clergy. His distorted aesthetic was an acquired taste for many, and he did not disappoint his admirers with his grotesque limbs and appendages. He seemed to paint with a sense of fury, and that urgency and anger communicated itself in his bold outlines and brushstrokes. His flagellation of the church, of society and of relationships in general became his calling card. It was only in a few, rare images of the Madonna that we saw him descend to an almost treacly poignancy. And it is this that is again so obvious in this beatific painting with its almost tranquil sensibility. The child appears self-absorbed in play while its mother gazes on placidly, untroubled as she looks squarely at the viewer. The nature of her clothes leads one to question whether she is, in fact, Madonna, while the colour of their skin alludes to a reflection of their connection with India. Whatever the outcome, there is no escaping the idealisation of the relationship, something that was extremely unusual in his work. PASTORAL QUIETUDE

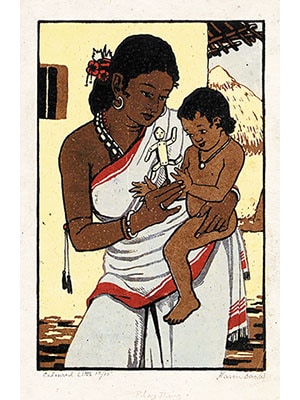

PASTORAL QUIETUDE

Haren Das (1921-93)

Colour Lithograph (1961)

In India, printmaking has failed to enjoy the rewards of ‘original’ art as a result of being widely misunderstood. Which is why, while several artists have dabbled with the medium, few founded their careers in printmaking. Haren Das is among the very few who remained exclusively a printmaker for the extent of his professional life. Recognised for his amazing play and experimentation with light, he devoted himself to bucolic scenes of pastoral Bengal, undeterred from that goal by ugly images of violence at the height of the nationalistic struggle or, later, Naxalite uprisings. For the artist, beauty seemed an end in itself, and he found this in his landscapes, in depictions of village life or in the nature of anthropological studies he conducted for various crafts. This colour lithograph is reminiscent of the nature of illustrations that were once popular in children’s books. While the wall and hut behind them are bathed in a golden light, the mother and child are captivated by a toy. A strength of Das’s prints was the use perspective in perfect proportion.

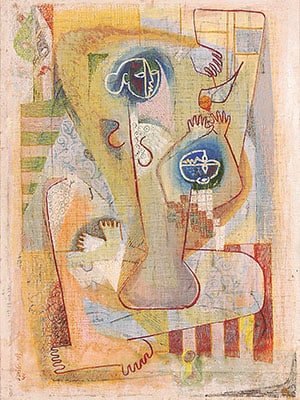

UMBILICALLY LINKED

UMBILICALLY LINKED

Jyoti Bhatt (1934-)

Tempera on khadi cloth pasted on board (1956)

Baroda-based Jyoti Bhatt invested in his own language of art, basing it on his surroundings and the relationships he saw around him. Drawn to an essential humanism—he would later veer into photography to document the vanishing way of life in the hinterlands—he sought to document a vanishing aestheticism rather than the angst his fellow artists were investing on their canvases. Bhatt’s lines were almost always lyrical, and though he sought beauty, he did not imbue needless sentimentality in a work, thereby saving it from appearing maudlin. At first view, his works appear simple, but there are hidden layers with which he builds his subject. Here, he creates a single body for the mother and child, thereby forging a unity of experiences between them. The diagonal line that distorts the mother’s body draws attention to her, while a medley of feet become a metaphor for the whole family. This separation of identities and unity of relationships could well be his representation for the Indian way of life.

HALOED IN THE ROUND

Prokash Karmakar (1933-)

Oil on plywood (1980)

This masterful painting by Prokash Karmakar is at once expressionistic as well as imbued with the ephemeral spirit of the Bengal School. At first glance, it is a mere rendition of the popular Mother and Child theme, in this case held together by the swirl of her saree, which provides both a sense of shelter from the world as she feeds the baby at her breast. But that same veneer of acceptability and respectability gets pierced by the voyeuristic nature of the viewer’s gaze, which fixates on their naked flesh. The viewer’s attention is also drawn to the mother’s face, which gazes out from her large, innocent eyes, almost those of a child herself. Is this young woman a willing mother? Has her own childhood been risked by the birth of another? Is it assurance that the infant seeks from his mother as he fastens his limpid gaze upon her face while sucking at her teat? Karmakar’s disturbing painting throws up more questions than answers. SLEEPING BEAUTY

SLEEPING BEAUTY

PT Reddy (1915-96)

Texture white and oil on masonite board (1962)

PT Reddy pushed a modernist agenda for the country’s artists long before Souza, Raza, Husain and others formed the Progressive Artists’ Group. An expressionistic artist who dabbled in the figurative form, he would search for resolutions in the abstract tantra in his later career but, for the most part, explored affiliations and connections in his work. In this, he never neglected the family, and included children within the fold even while representing their parents as lovers. His human forms seemed to consist of circles and ovals that he contrived to assemble in a manner that engaged the viewer, using just a few dabs of colour to create a sense of depth. In this painting, Reddy stays true to form. The naked body of the woman is not meant for pleasure it is simply a rendition of her as a form, and the lack of clothes is no pointer towards anything else. As the woman dozes after nursing, her hand holds the child protectively even as it lies awake in a scene that is all too familiar across households where it plays out endearingly. Soon, it will be time to wake up and go about her chores but, for now, she has the luxury of the contented company of her precious child. FOLK MODERN

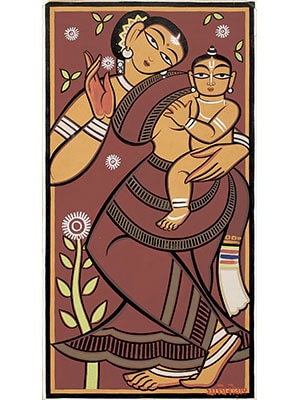

FOLK MODERN

Jamini Roy (1887-1992)

Tempera on boxboard

Among the earliest Indian modernists who renounced the realistic in favour of a visual language that was rooted in the soil of the land, Jamini Roy looked to the tradition of Kalighat paintings for inspiration. He found this in the simple, bold outlines and minimal expressions of folk art, which he co-opted for himself. His subjects were often the Santhals of the Bengal countryside and their love of music and dance. He was also drawn to Christian imagery, and imaginings of Madonna and Baby Jesus were often interchangeable with those of Yashodha and Krishna. In fact, there was no religious significance in these paintings, which remained secular images evocative of the tenderness that bound the relationship of any mother with her child. In this accompanying image, the mother nurses an infant at her breast. The frieze-like template is reminiscent of hundreds of similar images painted by him—not surprisingly, he ran his studio like a ‘factory’ with several artists and acolytes at his beck and call—and it is only the topknot of hair on the child’s head where, some day, a peacock feather might rest, that provides a clue to his representation as Krishna.

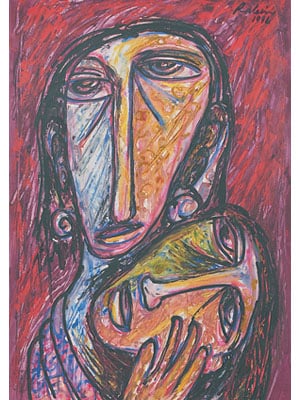

TENDER ANGST

TENDER ANGST

Rabin Mondal (1929-)

Water colour, brush and ink on paper (1996)

For much of his career as an artist, Kolkata-based Rabin Mondal has concentrated on the macabre. Moved by the inhumanity and suffering of those who are exploited, he has poured scorn on a society in which avarice and greed have subjugated every relationship. His stark, primitive paintings are uneasy reminders of the dark, malevolent forces that surround people, unleashing furies that leave behind death and degradation in their wake. This is what makes the painting under review so important. In reporting on the tender, Mondal is rising above his own parochial views of irony. What is interesting is his ability to use his familiar brushwork and figurative alteration, not as indictment but to recreate a more evocative mood in which the positioning of the two heads defines their relationship. In placing the mother as the nurturer and the child as the dependent, the artist has also sowed the seeds for a possible relationship as potential lovers. In hinting at a developing Oedipal complex, he provides fertile ground for the moral decay of humanity.

(All images courtesy Delhi Art Gallery)

First Published: Sep 06, 2014, 06:42

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Feb 05, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)