Harshavardhan Neotia: The restaurateur who eats at home

The chairman of the Ambuja Neotia Group talks about why it is important for him to sharpen his focus on the hospitality business at this stage in his life

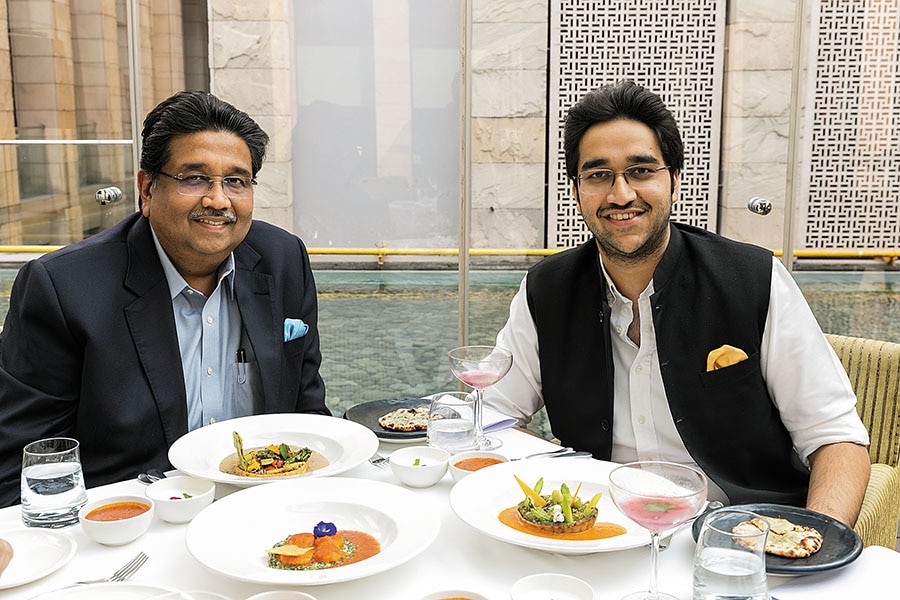

Harshavardhan Neotia, chairman of the Ambuja Neotia Group, with son Parthiv at Delhi’s Indian Accent, the poster child for luxury Indian dining

Harshavardhan Neotia, chairman of the Ambuja Neotia Group, with son Parthiv at Delhi’s Indian Accent, the poster child for luxury Indian dining

Photographs: Madhu Kapparath

My friends in school were not richie rich,” says Harshavardhan Neotia (57), chairman of the Ambuja Neotia Group, as he looks at his son Parthiv significantly, before continuing with his comparison of his days at La Martiniere for Boys in Kolkata with the lifestyle of the later generations. “In my class, most of the students were from service-class backgrounds, and some of my fondest memories are of going to the homes of friends, sitting on the floor in a two-room flat, and eating delicious home-cooked meals. It wasn’t like today, when you just decide to go out every evening to a restaurant. Restaurants were special-occasion indulgences back then,” he adds, even as Parthiv (22), who has just joined his father’s business as director, asks me in jest, “Will I get a chance to defend myself?”

We are sitting in the salubrious environs of Delhi’s Indian Accent, the poster child for luxury Indian dining. A chef’s tasting menu has been ordered—seven courses featuring many of the restaurant’s best-known dishes, puchkas with water in five flavours, baked beetroot and goat cheese, daulat ki chaat as well as some of the newer dishes that have made an appearance on the menu more recently after the restaurant shifted from its older location at The Manor to the new one at The Lodhi. But apart from the fact that this is a meal less ordinaire and that I am speaking to two generations of one of India’s leading business families, this could have been a fairly regular conversation between father, son and myself, the intermediary.  Chur chur naan

Chur chur naan

“The younger generation is much more experimental when it comes to eating out,”Parthiv ably defends his peers. “Even in Kolkata, thought of as a conservative city, new restaurants are doing well because younger people now want to try different things. It’s not as if we don’t like jhal muri or chai or street food but we also like modern Indian or fusion Asian and are ready to spend money on it.”

The way India eats out has changed phenomenally post economic liberalisation. Occasional restaurant meals have given way to a more casual culture of dining out and socialising for the younger generation. In this huge cultural change is a business opportunity that many with a desire for entrepreneurship are keen to leverage. The Neotias, whose real estate business comprises 70 percent of the group’s turnover, are no different. With Parthiv coming back to India after after graduating in entrepreneurship and economics from Babson College in the US and interested in this space, it’s an opportune time for them to grow restaurateuring muscle. And the first few steps have already been taken.

October saw the launch of Uno Chicago Bar and Grill in India, an American casual dining brand brought to the country by Ambuja Neotia Group’s hospitality vertical. The first outlet has come up in Noida with two more, in Kolkata and Bengaluru, expected this financial year, and another three in the next financial year to enable a pan-India footprint for the brand. Though the group already has interests in hospitality in eastern India—the members-only club Conclave, five-star Fort Raichak and luxury resort Ganga Kutir, restaurant brands like Sonar Tori focussed on Bengali food and Tea Junction built around the idea of chai and quintessential Bengali adda—this is the first time the Neotias are venturing into other markets in the country with a scalable, and young format.  Baked beet with masala peanut butter

Baked beet with masala peanut butter

As such, this signifies an intent perhaps to sharpen the group’s focus on the restaurants business. However, given its tricky nature (nine out of 10 new restaurants supposedly fail, according to a common warning passed around by hospitality veterans) and low return of investment, why focus on this business?

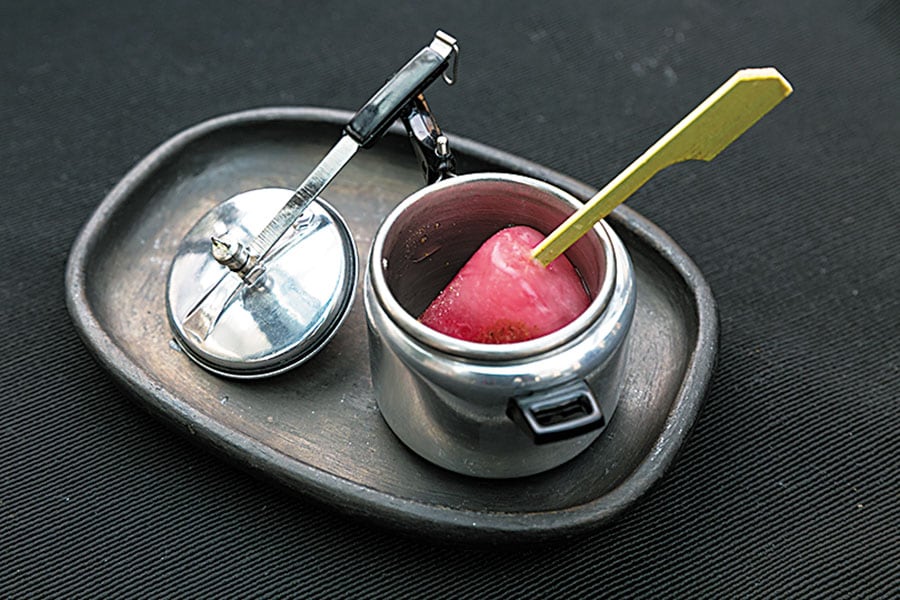

I let that question hang as we wait for the main course to appear on the table. We have already eaten every bite of the first few entrees—matar paneer daintily reinvented and some delicious corn kebab, both new on the menu and much appreciated. And even the pomegranate-churan kulfi sorbet that comes as a palate cleanser just before the chef readies to send out the mains has been polished off. But as we are waiting for the Morrel Mussalam and a plate of Bengali chenna accented with kashundi to make an appearance on our table, Neotia senior has confessed how he is not a “foodie” at all. “I have simple tastes I am a teetotaler and eat at home six days a week,” he says.  Pomegranate and churan sorbet

Pomegranate and churan sorbet

It’s a surprising statement. So, given that he is not a foodie and given the return on investment is not so great in the restaurant business, why get into it at all? I ask again, spooning up a bite of a soothing avocado raita that has now been placed before us.

Harshavardhan is candid. “The return on investment is much lower [in hospitality] than in real estate,” he acknowledges, “but hospitality and restaurants allow you to engage with a range of creative activities that are not possible in other businesses. Within restaurants, you are designing experiences. Having grown up in a joint family with many house guests and surrounded by food, art and culture, I like these influences to be a part of my work too. At this stage in my life, I want my life and work to be unified seamlessly.”

However, he is cognisant of the seriousness of the business. “You need constant innovation and effort. You can’t slip up even with one outlet,” he says, voicing the thoughts of many experienced restaurateurs who often warn ambitious newcomers about spreading too fast and thin. That is why the Neotias are taking one step at a time. Three outlets per financial year have been planned, which are expected to give the company time to build corporate bandwidth necessary to build scale. “Either you can have one mom-and-pop restaurant and operate it well, or hold on till you build enough bandwidth to scale up. If you try to grow without that, you are bound to fail.”  Puchkas with water in five different flavours were a part of the tasting menu

Puchkas with water in five different flavours were a part of the tasting menu

We’ve now reached out for our desserts. There’s a delicately sweetened custard apple cream in a jar, served with biscotti. As I dip the biscuit into the cream, I contemplate the equally mild strain of philosophy that has been underlining this conversation all through the afternoon. Harshavardhan’s take on business and life stem from it, and we get glimpses of this larger thought process as he says, “It is important to flow let things happen and let chance come.” It is something he has observed in his life, where things have not gone as planned and yet he has “not been unhappy”. (His real estate business, for instance, began as a passion project on the sidelines of the main cement business the family wanted him to join. It is now the mainstay of his business and has won him a Padma Shri in 1999 for contribution to social housing.)  Kashmiri morel mussalam with parmesan papad

Kashmiri morel mussalam with parmesan papad Winter vegetables and sarson ka saag tart

Winter vegetables and sarson ka saag tart

It’s this same strain of a larger philosophic outlook that I see when he adds how it is important to not chase numbers but “get things right”. “If someone gets into this business [restaurants] to make money, he will definitely fail. He must be genuinely interested in it,” says Harshavardhan.

As the last bite appears on the table, fittingly enough it is daulat ki chaat, chef Manish Mehrotra’s iconic recreation of the Delhi dessert that is made with milk froth, set in clay pots on cold winter nights and sprinkled with sugar. It’s a classic dessert favoured by old-world connoisseurs, a description that fits Harshavardhan well.

It’s light and subtle and also “as ephemeral as wealth”, he smiles.

First Published: Dec 01, 2018, 06:41

Subscribe Now