The dark side of plummeting solar prices

The cost of solar PV cells has dropped precipitously in the past few years due to a glut of cheap Chinese supply, and that's great news for nearly everyone—except the domestic manufacturers who can't

Image: Shutterstock (For illustrative purposes only)It’s never been brighter for the solar industry. Thanks to abundant low cost supply of photovoltaic (PV) panels from China, solar tariffs in India have dropped from Rs17.5 per kilowatt hour (kWh) in 2011 to as low as Rs2.44 at an auction in May —cheaper than the price of coal-based power. That is a big decrease from last year’s record low price of Rs4.34. At first glance, it seems the country’s goal of adding 60,000 MW of solar power to the grid by 2022 could be within reach.

Image: Shutterstock (For illustrative purposes only)It’s never been brighter for the solar industry. Thanks to abundant low cost supply of photovoltaic (PV) panels from China, solar tariffs in India have dropped from Rs17.5 per kilowatt hour (kWh) in 2011 to as low as Rs2.44 at an auction in May —cheaper than the price of coal-based power. That is a big decrease from last year’s record low price of Rs4.34. At first glance, it seems the country’s goal of adding 60,000 MW of solar power to the grid by 2022 could be within reach.

But things are not so sunny for everyone. India’s solar panel manufacturers are wondering how they will survive and adapt in a market where Chinese imports undercut them by as much as 18 percent, according to some reports.

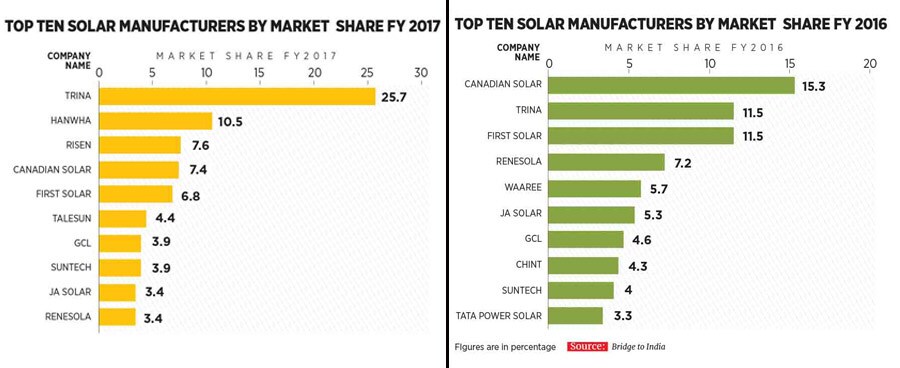

While tough competition from China is not new for the Indian solar PV industry, for the first time in FY 2017 no domestic manufacturer made the list of top ten solar module suppliers in the country, according to a report by solar power consulting firm Bridge to India. The combined market share of these Indian solar PV cells manufacturers stood at 10.6 percent in FY 2017, while Chinese imports made up 84 percent, with the rest imported from other countries.

Dire straits

Gyanesh Chaudhary, managing director and chief executive officer of Vikram Solar, a leading PV manufacturing company based in Kolkata, called the current domestic market a “graveyard”, as company after company struggles to stay afloat. “It’s a worrying situation overall”, said Chaudhary.

Dhruv Sharma, chief executive officer of Jupiter Solar, a Himachal Pradesh-based polycrystalline solar cells maker, said that most companies are winding down their production to 50 or even 25 percent operating capacity. “Chinese dumping is extremely destructive”, he said. “At such prices, even the Chinese companies are bleeding.”

The industry took a hit last year, when the World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled in favour of the US in a case filed against India’s policy of ‘domestic content requirement’, or DCR, in the solar panel manufacturing sector. Before the ruling, India required that power producers source a portion of their panels from domestic manufacturers. Without that support the nascent local industry has not been able to compete on its own.

Chaudhary thinks this is unacceptable, especially given similar DCR protections put in place by some individual states in the US. “I think India should rise up and take the strongest action against this”, he says.

Santosh Kamath, partner and head of renewables at KPMG India highlighted the dire straits the industry is in: “In the current form the industry will not sustain. It will probably close down over time.”

Bridge to India, in a report released in June, had a similar assessment, calling prospects for domestic manufacturers “very bleak” since the DCR policy was shelved.

To help keep this struggling industry afloat, a group of three manufacturers demanded anti-dumping duties on Chinese imports earlier in June —the third time in five years that such a request has been placed. Supported by the Indian Solar Manufacturers’ Association, the companies Jupiter Solar, Indosolar, and Websol Energy Systems called for duties on solar imports from China, Malaysia and Taiwan. Sharma of Jupiter Solar said if the government does not take action soon, companies will be forced to close their doors within the next three months. He sees predatory pricing as the “inherent root cause” of the struggles the industry is facing. “Once the government gives us a fair playing field, we will be happy to compete with China”, he said.

Vikram Solar is one of the larger Indian outfits with a 1 GW (1 GW is equal to 1,000 MW) manufacturing capacity, but even they are hurting in the current market conditions. Chaudhary says they have not seen a huge impact on his company’s sales because of its large international portfolio across markets in Africa and the UK, but it has been hard for the company to strategize for the domestic market. “We’re re-evaluating our India strategy considering the noncommittal ways [of the government]. It’s been really tough for us to be plan our capacities.”

With access to such cheap panels buoying solar project development, there is likely little will to raise costs. The solar industry across the globe has been striving to achieve cost parity with fossil fuels. And power producers are pleased with low cost materials. But some feel that the emphasis on cost above all else – especially quality – may lead to compromises in other areas.

“Renewables have a long life ahead”, says Chaudhary. “We can gradually achieve cost parity while achieving value. The way the industry is evolving, cost seems to be the overriding factor, over and above everything else, which is disappointing.”

With Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambition to achieve 100 GW of solar power generation by 2022, India has a long way to go from its current level of 9,013 MW (cumulative installed capacity till the end of 2016-17). The way the industry is moving now, it looks like most of the remaining solar capacity to be installed in India will be fueled by imported equipment, unless the government takes action soon. Power minister Piyush Goyal has, in the past, indicated that he would like to foster the creation of a renewable energy ecosystem in the country, which not only includes green energy projects but manufacturing of the relevant input components too.

But would instating anti-dumping measures simply be forestalling the inevitable? Vinay Rustagi of consulting firm Bridge to India thinks so. “Anti-dumping duty is at best a short term life support,” he said. “It can only make players viable in the short term--it does not aim to make the sector competitive in its own right.” A report from Bridge to India characterizes the sector as “obsolete, sub-scale, and uncompetitive”.

Indeed, Indian solar panel manufacturers struggle from issues of high cost of capital and low scale. Indian companies are a fraction of the size of foreign companies like Chinese-owned Trina Solar, and US-based First Solar, and therefore lack the capital to invest in new technologies and scale up their facilities. In addition, the raw materials come from China as the country controls as much as 90 percent of the market for rare earth minerals, several of which are used in the production of thin film solar panels.

To contend against such odds, Rustagi believes India needs a more comprehensive, holistic, policy approach. “Until and unless there is national level cogent plan to support domestic manufacturers, I think they will struggle to compete.”

That plan does not seem to coming anytime soon. Today, The Economic Times reported that the finance ministry has rejected a proposed 20,000 crore subsidies and incentives plan to support the struggling domestic industry.

High level policy, or the lack thereof, is keeping international solar giants from opening plants in India as well. First Solar, a US-based solar energy solutions company, has helped develop projects totalling 1.3 GW in India and sees the country as a major market. But when it comes to manufacturing the majority of their equipment, they prefer a country like Malaysia. Sujoy Ghosh, First Solar’s country head for India, said while they are always looking for new countries to expand manufacturing into, high cost of capital and steep corporate tax rates were keeping them from opening a plant in India. “Instead of creating restrictions in the market, how do you incentivize manufacturing to be more competitive?” he said, pointing to the large amount of low-cost debt that successful Chinese companies were able to avail.

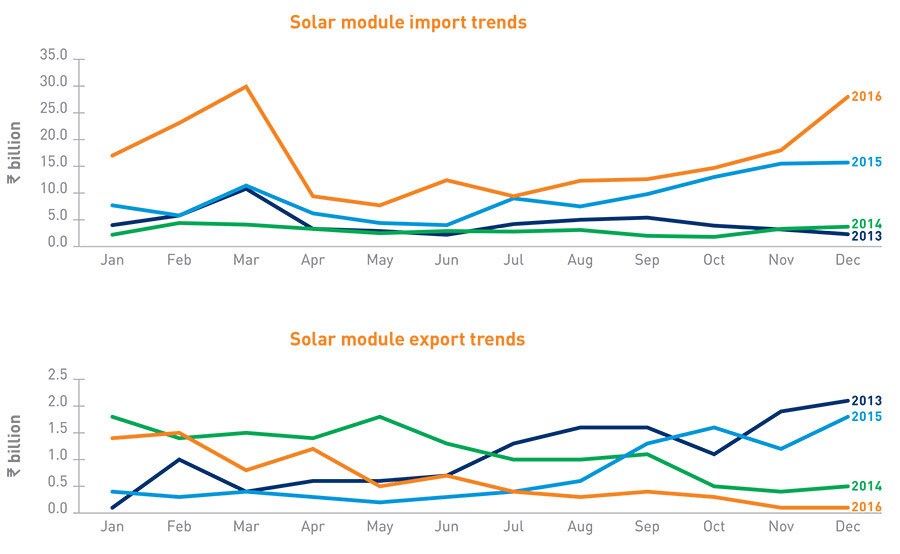

Building a competitive manufacturing sector entails both incentives for scale and innovation as well as protection from predatory pricing. At the moment, neither exist, and while the government has promised to support a healthy PV manufacturing industry in the past, it has not taken any action to do so since its failed appeal against the WTO ruling that undid domestic content requirements.  Source: India Solar Handbook 2017, Bridge to IndiaThe case for local production

Source: India Solar Handbook 2017, Bridge to IndiaThe case for local production

A KPMG report from 2015 had estimated that the solar manufacturing sector in India could capture 50 percent of the market share by 2020 and create 50,000 jobs. That appears to be a lost opportunity as things stand at present.

Besides the loss of jobs and GDP potential, there are strategic reasons for a local manufacturing sector. Looking towards the future, with renewable energy on its way in and fossil fuels on their way out, cutting edge solar technology could be become as strategic a national resource as oil reserves. “You have to look at security in the long term”, says Kamath of KPMG, cautioning against depending too much on one exporting country. Geopolitical forces or market fluctuations in China could disrupt the availability of such products, and throw India’s renewable growth plan off balance.

What’s next?

The immediate future for manufacturing firms in India is a dark one. For many, the decision now is to either convince the government to instate protections, or shut down. Some companies may be able to diversify their offerings and transition into the operation and management space, but for many, that will be a difficult shift.

Without clearly communicated policy goals, companies are still floundering to plan ahead. In response to an email seeking comments, Jatindranath Swain, joint secretary of the new and renewable energy ministry said that “the promotion of domestic industry is a priority of the government”, but didn’t elaborate further.

Chaudhary of Vikram Solar is still hopeful that the domestic market for solar power equipment will survive and grow. “We’re not giving up on the Indian market. I think quality will survive.”

First Published: Jun 23, 2017, 15:28

Subscribe Now