The growth-rate cuts conundrum

Low rates reflect slower economic activity and weakness rather than strength; they have also reduced the political appetite for much needed policy changes

Isaac Newton believed that truth is found in simplicity, not in multiplicity and confusion. Based on current interest rate policies, central bankers in developed markets clearly believe in the opposite.

Since Lehman Brothers left the mortal coil, there have been more than 600 rate cuts.

Over the same period, central banks have injected over $12 trillion under quantitative easing (QE) programmes into money markets. Over $26 trillion of government bonds are now trading at yields below 1 percent with over $6 trillion currently yielding less than zero percent.

These policies, according to policymakers, have been crucial to the ‘recovery’.

Financial market valuations have increased but remain reliant on low rates and abundant liquidity. The effect on the real economy is less clear. Policymakers argue that without these actions to support growth, employment and investment would have been weaker It is a proposition that is, of course, impossible to test.

Now there is increasing confusion about future interest rate policy. For the last 12 months, US Fed Chair Janet Yellen has prevaricated about increasing interest rates. Until the 25 basis points increase in December 2015, the Fed did not have a rate increase for 112 months—the longest since World War II.

Markets expect that stronger US employment numbers and an improving economy will drive rate rises in 2016. Puzzlingly, the Fed chair has hinted that more QE or negative interest rates are possible, should conditions dictate. There is little agreement among the Fed governors about the appropriate policy path.

Yellen also has to worry about non-terrestrial matters. Representative Brad Sherman recently told Yellen that God does not want her to raise interest rates until May: “If you want to be good with The Almighty, you might want to delay until May. God’s plan is not for things to rise in autumn, that is why it is called Fall.”

The Fed’s OMC (open market committee) is now referred to commonly as the Open Mouthed Committee or, more charitably, the Open Minded Committee.

Everyone else is cutting rates

In Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi has hinted that he will consider lowering rates further. European central banks are already operating negative deposit rate policies. The ECB is at minus 0.3 percent, Swiss policy rate is minus 0.75 percent and Sweden’s policy rate is minus 0.35 percent.

In October 2015, Italy sold two-year debt at a negative yield for the first time. Investors are now paying to lend to a country which has one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the world. It is also a country synonymous with pizza, pasta, political gridlock and fiscal indiscipline.

The Bank of England has suggested that the UK’s interest rates may not increase in 2016 or even in 2017.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has promised additional easing if necessary “without hesitation”. The Japanese have even rebranded QE as QQE (quantitative and qualitative easing). The qualitative is central banks talking about easing.

The People’s Bank of China, China’s central bank, cut benchmark interest rates six times in the course of a year to a record low of 1.5 percent in a bid to support an economy which is forecast to grow at its slowest annual rate in 25 years.

Further interest rate cuts are forecast in Australia, New Zealand and also many emerging countries.

Central bankers argue that the case for increasing rates is limited. Despite record levels of monetary stimulus, growth remains lacklustre. Forecasts of economic activity have seen regular downgrades over the last 2-3 years. Disinflation and deflationary pressures remain, with low commodity, especially energy, prices likely to continue. Overcapacity in many industries limits the ability to increase prices.

Even in the US, where the economy is performing better than other developed countries, wage pressures are limited. Fed Chair Yellen’s concerns about tight labour markets miss the point that the market is now increasingly global. There are significant surplus labour forces in other nations which can be accessed through global supply chains.

Central bankers dismiss criticism that the policies are, at best, ineffective and, at worst, damaging.

Low rates have created problems for savers and retirees around the world. Pension funds are in trouble with rising levels of unfunded liabilities. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble has drawn attention to the increasing solvency problems of insurance companies and retirement funds in an environment of low or negative rates.

Debt levels are continuing to rise from unsustainable to even more unsustainable. Low rates have distorted financial markets and created asset price bubbles in shares, property and other investments.

Whatever the initial benefits, low rates and unconventional monetary policy are increasingly counterproductive.

Former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King spoke for many when he questioned the continuation of these policies: “We have had the biggest monetary stimulus that the world must have ever seen, and we still have not solved the problem of weak demand. The idea that monetary stimulus after six years... is the answer doesn’t seem [right] to me”.

Japanese interest rates have been around zero for almost a decade. The BoJ has undertaken nine rounds of QE. The central bank balance sheet is approaching 70 percent of GDP. It owns a significant proportion of the outstanding stock of government bonds and equities. But the policies have not restored growth or addressed the problems of demographics or need for changes in Japan’s economic model.

The effect of further rate cuts is also diminished by continuing trade and currency wars. Each individual cut is increasingly offset by competing reductions elsewhere in the world.

Despite denials by policymakers, countries are using monetary policy to devalue currencies to gain competitiveness and capture a greater share of global demand. Individual nations’ actions are now redundant in a nugatory race to the bottom in interest rates and currency values.

Maintaining interest rates at low ‘emergency’ levels for an extended period also makes it increasingly difficult to increase them to more normal levels.

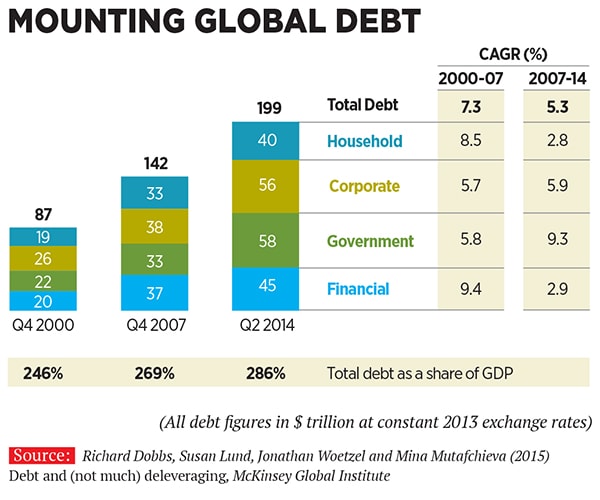

Increase in debt levels is now a constraint on monetary policy. Total public and private debt in major economies has increased, not decreased. The table (above) sets out the changes in debt levels in the global economy. Total debt has continued to grow at a slower rate than before the global financial crisis but remains well above the corresponding rate of economic growth.

Households in the hardest hit countries have deleveraged. But overall household debt has continued to grow. Higher public borrowing has largely offset debt reductions by businesses and households.

Between 2007 and 2014, the debt of households and non-financial corporations in advanced economies has declined modestly by around 2 percent of GDP. (In comparison, global private sector debt grew by 19 percent of GDP between 2000 and 2007.) However, the decrease is largely driven by four economies (the US, UK, Germany and Spain) where private sector debt has declined in relation to GDP. In Sweden, France, Belgium, Singapore, China, Malaysia and Thailand, private sector debt has grown by more than 25 percent of GDP during this period.

Between 2007 and 2014, the ratio of public sector debt to GDP in advanced economies increased by 35 percent of GDP, compared to an increase of 3 percent between 2000 and 2007.

Higher debt levels mean that the financial impact of higher rates is attenuated. This is evident in the concern created by further rate hikes in the US.

In Australia, a 0.15-0.2 percent increase in mortgage rates to reflect increased capital to be held against these loans caused significant uncertainty in the domestic housing market.

In the US, a 1 percent rise in rates would increase US government interest costs by around $180 billion from its present level of around $400 billion. Unless offset by increased economic activity, it would increase the budget deficit and government debt levels.

The normalisation of rates to, say, 2.5-3 percent may prove financially and economically destabilising.

Low rates and QE have also reduced the political appetite for much needed policy changes. Lower interest costs have sapped the willingness for fiscal reforms, debt reduction and structural reforms.

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Governor Glenn Stevens recently admitted that cutting interest rates may not be effective in restoring growth. But the governor clarified the RBA policy: “The fact that it isn’t interest rates that are holding things back isn’t the same thing as saying that there’s no benefit from lowering them.” Apparently, the RBA is using “a path-of-least-regret framework”.

Asset markets, especially equities, have rallied repeatedly on the continuation of low rates. Like Charles Dickens’s literary character Oliver Twist, investors have lined up to demand “more”.

But low rates reflect slower economic activity and economic weakness rather than strength. This means, at some stage, a dramatic reassessment of asset prices is now inevitable, either because interest rates increase or because they do not. The volatility in financial markets in the early days of 2016 is a clear marker of increased fear that central bank policies have run their course. QE now connotes quantitative exhaustion rather than quantitative easing.

As Albert Einstein observed: “Confusion of goals and perfection of means seems, in my opinion, to characterise our age”.

Satyajit Das is a former banker whose latest book The Age of Stagnation, was released in India in January 2016

First Published: Feb 11, 2016, 06:30

Subscribe Now