Using Nostalgia for an improved brand communication strategy

Brands use nostalgic theme to expand their target market and create a link between generations

Today, many brands are jumping on the nostalgia bandwagon. This retro trend has become an international phenomenon and is affecting the entire marketing mix. Some brands have developed products evoking nostalgic flavor of childhood memories. In the food industry, for example, Chuao chocolatier has recently introduced a Rocky Road bar that contains salted almonds and vegan marshmallows. Other brands have chosen to re-run their best historical ads, such as the detergent brand Persil, for its 100th anniversary to capitalize on its longevity accompanying consumers in their lives from the "good old days" until now, thus enhancing brand credibility and authenticity. Finally, a nostalgic atmosphere can be achieved through the interior design. Jack Daniel’s whiskey has come up with a classic cool with a special edition to mark Frank Sinatra’s 100th birthday. Launched last December at Las Vegas’ airport with interactive stations for tasting, viewing and listening to all things Frank Sinatra did, the initiative expanded to 200 airports, coinciding with the evocative “Legend” campaign.

Nostalgia can also respond to segmentation issues. Brands use nostalgic theme to expand their target market and create a link between generations. For example, to launch PlayStation 4, Sony has set up a YouTube campaign chronicling the evolution of the iconic gaming console, presenting a series of videos covering the product’s 19-year history. In the same vein, to foster the latest version of Internet Explorer from consumers who grew up in the ’90s, Microsoft has proposed a time-traveling journey via a two-minute video sporting “You grew up So did we” as a tagline.

Capitalizing on the emotions it arouses among consumers, nostalgia gives brands a sense of credibility, authenticity, durability and quality, as well as emotional bonding – thus attracting the interest of managers. Although marketing practitioners widely use nostalgia as a communication tool, no study has sought to define the conditions for its application in brand management. Given its impact on consumption, understanding what nostalgia means to consumers appears to be of particular importance.

The article is divided into four sections. The first section examines the interpretations of nostalgia in litterature. The second section explains why the use of nostalgia in brand management is relevant. The third section proposes four possible applications for nostalgia in brand communication management, related to four nostalgic consumers profiles. The last section emphasizes the main risks of nostalgic branding.

What is nostalgia?

While medicine presents nostalgia as the pathology that devastates persons physically away from their countries (nostos = return algos= pain Hofer, 1688), the great philosophers of the 18th century, Rousseau and Kant, described it as a regret for a period that has passed. In psychoanalysis, nostalgia is related to two poles: an object pole which considers nostalgia as a desire to go back to the womb and a narcissistic pole which states it as an identity injury. In the 20th century, sociologists associated nostalgia to the discontinuities of existence: individuals feel nostalgia during alteration stages in their lifes and use nostalgia to preserve their identity (Davis, 1979). Psychologists recognize two temporal approaches in the nostalgia concept: present (i.e. maladjustment to the environment Rose, 1948) and future (i.e. an anguishing perception of the future Nawas and Platt, 1965).

In marketing, academics suggest multiple definitions of nostalgia: a mood (Belk, 1990), a preference (Holbrook and Schindler, 1991), a state (Stern, 1992), a desire (Baker and Kennedy, 1994), an emotion (Holak and Havlena, 1998). Holbrook and Schindler’s definition (1991, p. 330) is undoubtedly the most cited reference: "A preference (general liking, positive attitude, or favourable affect) toward objects (people, places, or things) that were more common (popular, fashionable, or widely circulated) when one was younger (in early adulthood, in adolescence, in childhood, or even before birth". According to this logic, nostalgic brands are defined "brands that were popular in the past (and are still popular now), whereas the non-nostalgic brands as "brands that are popular now (but were less so in the past or did not exist in the past)" (Loveland, Smeesters and Mandel, 2010).

Why using nostalgia in brand communication?

&bull Nostalgia “an idealization system of a posteriori memories

A reason to justify the use of nostalgia in brands communication strategies is the idealization system of « a posteriori » memories. Nostalgic memories, recalled at the present, are not an identical copy from the past. Beyond memory failures linked to the age, nostalgia goes through the negatives aspects from different events. Nostalgic perspective is informative (acts selection among what have been an « a priori » past), transformable (in changing memory semantic contains), creative (in making up events). It translates into a gap between these situations perceived by embellishment. It is possible thus to distinguish several level of nostalgia, from real to simulated.

&bull Nostalgia and consumer - brand relationships

Nostalgia appears via an emotional transfer on stimuli that evoke old memories. These stimuli can be brands, which, due to their age and their “revivalist” features, can arouse specific attitudes and behaviours. Kessous and Roux (2010) show that the nostalgic brands benefit from a high level of attachment and identification. Holbrook and Schindler (1989) underline that the preferences of long-term cultural consumption emerge from the end of the teenage years to the beginning of adulthood. Sierra and Mc Quitty (2007) observe the significant impact of positive cognitive and affective dimensions of nostalgia on the purchase intent of nostalgic products. Sierra and Mc Quitty (2007) demonstrate that advertisements mentioning personal nostalgia reveal more efficiency than the non-nostalgic advertisements. Kessous (2011) observe that the consumers realise their memories in collecting and/or in giving by-products from nostalgic brands.

Which targets?

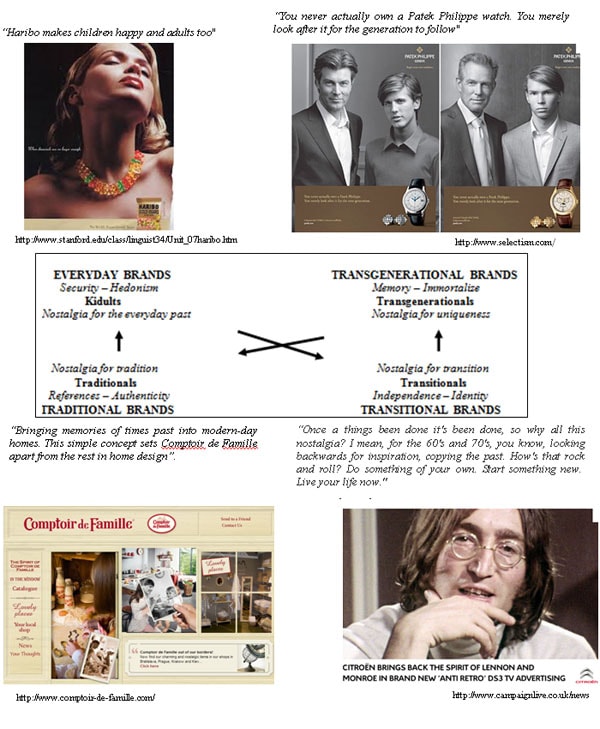

It is possible to identify four types of nostalgic consumers (kidult, traditional, transitional and trans-generational) and four nostalgia applications for brand communication that are related to the above profiles (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four nostalgic profiles and four brands perceived as nostalgicWe conducted 49 semi-directive interviews in 3 stages. First, 20 subjects were asked to discuss the products and brands connected with a pleasant moment in their lives. A year later, they were interviewed again and shown pictures of the nostalgic brands previously mentioned and were asked to associate what came to their mind when they saw these visuals.

Finally 17 months later, the participants discussed the memories they associated with 4 photographic forms representing four important stages in their lives.

A semiotic analysis of these interviews resulted in the following classification of consumers and the description of the possible corresponding brand communication strategies:

&bull Kidult

Kidults belong to the Generation Y (1978–1988) who are nostalgic for their childhood and satisfy their need for security through regressive consumption. In order to reach these young people in Generation Y, advertising with TV icons that were popular in the 80 and 90s for product categories such as candies and video games appears suitable. A typical brand that target "kidults" is Haribo, a brand of candy created in 1920. Through its playful character Hariboy and its targeted slogan ("Haribo, life's beautiful – for grown-ups and little ones") the brand stimulates the fondness for sweet things of the young and less young. In France, Haribo is a fashionable candy. To reach people in their 30’s, the brand organizes special Halloween nights in discotheques. The success of Haribo's strategy is beyond question: its paying subscription club has more than 7,000 fans. The Haribo Sweet Museum has existed since 1996. Top-of-mind awareness of the brand in the under 35 years bracket is 68%. Global brand awareness is 99% for 15-24 year olds and 96% for 35-49 year olds (BVA Study, 2008).

&bull Traditional

They are individuals from Generation X (1968–1977). Nostalgic of traditional celebrations, they need points of reference. Brands targeting this group should play on authenticity of their products. The emblematic example is that of Comptoir de Famille whose inspiration arises from second-hand trades. Counter of Family is connected with the collective memory to wake up the memories of the individuals and to promote objects which they had the feeling they have already seen at their grandparent's or who dip back them into their childhood. Advertising campaigns use "old" turns of phrase and some colours a bit aged as the ivory, the raw or the dark red. They stage moments of life which remind memories: a Sunday in the countryside, Christmas time… In catalogues, the “old” photograph, in black and white, is always put in counterpoint with the colour photograph from the product of today. After 27 years and with an annual growth of over 20% and forays into the international arena, Comptoir de Famille brand count as the strongest success in the sector. Contagious passion for the products has led to the creation of 32 branded stores, including 10 branches and 22 licensed stores and franchises. There are now 1000 multi brand points of sale in France and another 600 across the world.

&bull Transitional

Made up mainly of Baby-Boomers (1948–1967), this group sees nostalgia as the definition and maintenance of their identity. For them, advertising should highlight objects of autonomy (i.e. vehicles), "forbidden fruit" items (i.e. cigarettes) or brands which have great importance in constructing identity (i.e. perfume). Brands targeting this group can choose to re-launch products that were symbolic in the 20th century and are representative of a transition stage in life. The communication strategy associated with nostalgia can satisfy a logic of differentiation, emphasizing that the brand, associated with its period, was the forerunner in its domain but also remains timeless. Typical examples are the New Beetle, Mini, Fiat 500 and DS3 that are replicas of period cars with curves and technical attributes updated. In its advertising campaign, Citroën's DS3 uses two universal icons – Marilyn Monroe and John Lennon, who deliver the same message: "Do something of your own, don't look backwards, invent your own style, live your life here and now!" With the DS3, Citroën is not trying to recycle the DS, but to recapture the values that made it a myth.

&bull Trans- generational

For this group of people born after World War II (1928–1947), “consumption may be used as a means for transmission of valuable objects and brands such as jewels or watches and Advertising might create a romantic atmosphere, using black and white visuals and iconic songs”. Brands that take an interest in transgenerationals can play the uniqueness card and put an accent on the symbolic and transmissible dimensions of the object. Here, the added value of nostalgia is a very unique brand heritage. Patek Philippe, a Swiss watch brand founded in 1839 is a good example. Its values "respect the past/fascination with the future" and its "Generation" campaigns, in vogue since 1996, reinforce an intimate link with their customers. Patek Philippe´s black and white advertisements and the famous claim "You never actually own a Patek Philippe watch. You merely look after it for the generation to follow" contributes to the awakening of nostalgic feelings. The brand targeted fathers and sons, first. Having successfully established the intended positioning, the company started portraying mothers and daughters, thus extending their markets from masculine to feminine.

Nostalgia: a miracle cure against failure?

The previous section identifies the benefits that the different targets find in the consumption of nostalgic brands. Thus, for the kidult nostalgia meets a need for security and hedonism through the consumption fun and regressive brands. For the traditional group, nostalgia promotes a need of marker translated by the use of a genuine brand. For the transitional, it responds to a quest for independence satisfied by an attachment to decisive brands in their identity construction. Finally, for the trans- generational group, nostalgia contributes to a need of memory through the attachment to brand that represent a "better" time.

In practice, these benefits for the consumer can be translated into incremental benefits for brands. Thus, the main differential advantage of brands targeting the kidults is the possibility of broadening their target market in passing, for example, from the child market to the adult one. Brands, for the “traditional”, develop a traditional image strengthening their capital of credibility. Brands, for the “baby boomers”, have an advantage in terms of differentiation, recalling their precursor and timeless sides. The differential advantage of brands targeting the “trans-generational” is the guarantee of quality and continuity which they acquire, seniority being synonymous with stability.

Finally, let’s remind the main risks in which nostalgic brands could be exposed. The first managerial risk is the "has-beens" and "old-fashioned" image which brand can develop. This is particularly the case when the real nostalgia is "too remote" of contemporary values and therefore unsuited in term of up to date.

The second managerial pitfall is the brand’s authenticity loss which could arise when nostalgia is stimulated via "too fake" memories. A typical example is that of the fast-food chain Kentucky Fried Chicken Corp. In 1995, managers thought the brand required some advertising help from founder Colonel Harlan Sanders. But, the problem was that Sanders died in 1980, and KFC could not find old film clips of him that would fit with a current commercial. So KFC dressed up an actor in the colonel's white suit and broadcast black-and-white TV commercials that pretended to show the founder spouting his special brand of homespun wisdom. However the effort to reinvent history didn't work and KFC was severely criticized for defaming the dead. One year later, the ads were removed.

About the Author

Aurélie Kessous is the author of numerous articles on the role of nostalgia in the relationship between consumers and brands. A researcher at INSEEC, her works mainly fall into the field of retro-marketing and healthcare marketing. The results of her studies have been published in international academic journals such as « Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal » in 2008, «Recherche et Applications en Marketing» in 2010, «Management et Avenir» in 2012 and also in Anglo-Saxon journals, for example «Marketing ZFP: Journal of Research and Management» in 2013

First Published: Mar 12, 2014, 06:12

Subscribe Now