Instamojo: Mojo's working, for now

Payments are just the starting point for Instamojo, but does it have what it takes to evolve into a full stack online commerce enabler?

Even when the writing was on the wall, Instamojo CEO Sampad Swain stuck to his gut and overcame trying times

Even when the writing was on the wall, Instamojo CEO Sampad Swain stuck to his gut and overcame trying times

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes IndiaIn the summer of 2017, Sampad Swain found himself stuck in a quagmire. Instamojo, a startup he had co-founded five years ago, was up the creek.

“In July last year, we had a month’s money. We would have given the month’s salary. We would have managed maybe, let go of a few people. We would have survived but would not have been able to invest in growth,” says Swain, sitting at the firm’s office in a tony Bengaluru neighbourhood.

It was a strange paradox. Investors eluded Instamojo despite the firm doing brisk business. The number of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) using Instamojo’s payment platform was growing at 8-12 percent every month. Also, Swain ran a tight ship sans any exuberance and profitability was at an arm’s length. “We were burning about ₹100 and we were making about ₹95. We would have been hitting profitability the next month and then the business would have depended on cash flow,” says Swain.

From the looks of it, Instamojo —lean, frugal and steady—was the perfect startup to bankroll for venture capital firms. Yet, nobody invested, leaving the firm in a quandary. Protracted discussions with strategic investors, including Paytm and Shopify, the $17.5-billion (by market capitalisation) Canadian company that provides multi-channel commerce platform to small businesses, did not fructify, according to three people aware of the discussions. Swain declined to comment on specific conversations.

Instamojo had been living on borrowed time for a few months. The firm was shrouded in similar misery around December 2016, when an imminent shutdown was averted with fresh capital infusion by existing investor Kalaari Capital. “We got about six to eight months’ money to run. We used it to become cash positive and turned around the entire system,” says Swain. Among others, Swain was constrained to trim the workforce by about a third. The founders—Swain, Akash Gehani, Aditya Sengupta and Harshad Sharma—stopped drawing a salary while the company’s top brass took hefty pay cuts.

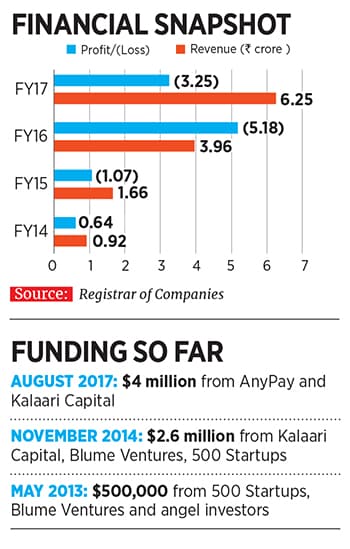

Documents filed with the Registrar of Companies indicate that Instamojo has been consistently paring losses. The company was in the red to the tune of ₹3.25 crore on revenue of ₹6.25 crore in fiscal year 2017 as against red ink of ₹5.18 crore on revenues of ₹3.81 crore the year before.

Ask Swain why he finds himself sitting on a ticking time bomb every few months, and he says with a wry smile, “They (investors) were possibly not getting the message. Maybe I did not do a good job in explaining as well.”

The torrid times are a thing of the past. In July last year, Japanese payments firm AnyPay, along with the existing backers, invested $4 million in the company. The money has been put to good use. Today, Instamojo boasts of more than 5 lakh sellers under its fold—to put things in perspective, Shopify, after 14 years in business, is estimated to have about 60 lakh sellers—and adds approximately 1,000 sellers per day, without any significant spend on marketing.

“Right now, the payment volume is approximately ₹1,500 crore per year. We want to take that ₹10,000 crore in the next three years,” says Swain. “This won’t be tough to achieve as we have got that critical mass. We have done that without branding or advertising activities. At 1,000 sellers a day, if you do a run rate, it comes to about 3.6 lakh merchants a year. The idea is to see if we can take it to a million sellers with advertisement.”Instamojo was largely evaluated as a payments business, and rightly so. For the longest time, the company enabled its audience—small online sellers who make on an average ₹10-12 lakh in annual sales—generate a payment link and share it with their customers to accept payments. The ancillary verticals were still a paper plan, far from being executed. It launched an online store builder in 2015, which Swain describes as a “stripped down” version of Shopify. All the users needed to have was a phone number and a bank account. This saved them the onus of integrating with payment gateways such as PayU, CC Avenue, Razorpay or BillDesk among others, which would entail a hefty integration charge to the tune of tens of thousands of rupees as well as an annual maintenance fee. Instamojo, instead, charged a flat 2 percent of the transaction value as commission.

Shopify had made a fortune by catering to small sellers across the globe. The firm, though in the red (fiscal 2017 loss stood at $39 million), saw revenues snowball to $673 million as against $389 million in the year ago period.

Swain aspired to create something similar—a service provider that would cover the whole nine yards, including payments, logistics, lending and advertisement among others, for small businesses—and for good reason. According to the National Sample Survey conducted by the ministry of statistics and programme implementation in 2015-16, India was home to about 6.34 crore unregistered non-agriculture MSMEs, of which, as many as 6.3 crore were micro enterprises earning less than ₹25 lakh annually, essentially Instamojo’s target audience.

Payments, thought Swain, would be the starting point before Instamojo evolves into a full stack online commerce enabler. The company’s model of charging a flat fee as against differential rates charged by payment gateways—a separate fee for instruments like NEFT, IMPS or card payments—also fetched the company margins that were about ten times higher than a typical payment gateway, claims Swain.

“Whatever we wanted to do would either allow the merchant to adopt digital faster or grow their digital business faster. If you are already digital, grow with Instamojo faster, and if you are not, become digital with us,” says Swain of his pitch to potential customers.

However, it was easier said than done. Aggregating a formidable user base turned out to be a gargantuan task. “You can’t force business to business behaviour beyond a point. There is an adoption curve. You simply can’t go to a seller saying that we will give you things for free, so please use this. Unless you give cash backs and throw that kind of money, which we never had... so we never tried that game,” says Karthik Reddy, managing partner at Blume Ventures. Until then, Instamojo had snared $3 million from Kalaari Capital, Blume Ventures, 500 Startups and a clutch of angel investors, including Google India Managing Director Rajan Anandan.

Payment businesses, thanks to their wafer-thin margins to the tune of 25-50 basis points (25-50 paise on a ₹100 transaction), require high transaction volumes to become palatable to investors and Instamojo, with about 1.5 lakh users, was found lagging.

“Instamojo was seen as a payment business and even the largest payments businesses haven’t figured out how to make money of payments per se, because, essentially, it is an unfortunate journey to a zero margin. You cannot improve margins by simply doing payments and have to be able to use payments as a mechanism to drive other services,” says Reddy. “Whatever we tried to position Instamojo as in the long term, unfortunately, we did not have the scale or capital to invest in offering more than simply this payment collection services. And the market basically said why would I fund another payment company.”

In August, Instamojo took a step forward towards metamorphosing into the full-stack operator it had aspired to become, with the launch of logistics and micro-lending services. Swain claims to have disbursed about ₹100 crore in loans within the first week of launch. Work is under way to launch an advertisement service for the sellers.

All these, coupled with healthy margins from the payments business, which currently accounts for about 90 percent of the firm’s revenue, have made Instamojo an attractive investment destination. The firm is in talks to raise about $5-7 million more from existing investors, say two people aware of the discussions. Swain declined to comment.

With a razor-sharp focus on small businesses, Instamojo is catering to an audience not many businesses vie for, say industry observers. “Instamojo is classically one of those businesses focussed on the long tail—the home entrepreneurs, the freelancers and the like—but getting them on board is way more difficult. It is a difficult business to build without subsidising users, without spending on paid marketing. That is why Instamojo to me is a great business as it has grown with minimal spend on user acquisition,” says Kunal Walia, managing partner at Khetal Advisors, an investment bank.

Still, there is competition. A whole lot of businesses such as Kartrocket, Martjack (acquired by Capillary Technologies) and Shopmatic among others offer to build an online presence for businesses. Then there are the online marketplaces such as Flipkart and Amazon, which not only handle payments and logistics but also acquire users for the sellers. Shopify, the largest in the segment, is also fairly active in India. Businesses such as Meesho, which engages a battery of sellers trading largely unbranded goods, could also chip away at Instamojo’s user base.

Swain is mindful of the challenges, but undeterred. “It took us five years to reach where we are today. It is not like we got millions of sellers on day one,” says Swain. He is very clear about the firm’s USP. “It (Instamojo) works for small businesses, because the complexities are lesser.”

First Published: Oct 24, 2018, 11:32

Subscribe Now