Sow what you read

Stationery makers are giving consumers eco-friendly options

(Clockwise from left) Saurabh Mehta, founder and CEO of BioQ Eco Solutions Roshan Ray, founder of Seed Paper India Renuka Shah of Jalebi

(Clockwise from left) Saurabh Mehta, founder and CEO of BioQ Eco Solutions Roshan Ray, founder of Seed Paper India Renuka Shah of Jalebi

Image: (Clockwise from left)Amit Verma Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India Aditi Tailang[br] Imagine a plant growing out of a pencil after you’re done using it. Or a piece of used paper that you can grow in a pot instead of tossing it away. This is how some players in the stationery industry, traditionally damaging to environment, are reinventing themselves into eco-friendly entities.

Sustainable stationery makers are coming up with innovations such as making pencils by rolling graphite into recycled paper or newspapers. In pencils that can be planted, seeds are fixed to an attached capsule that dissolves in soil.

Innovations extend to sustainable paper too. Roshan Ray, founder of Seed Paper India, talks about how seeing his wedding cards get discarded inspired him to switch from his family business of hand-made paper to focus on seed paper. “Last year, we made calendars for around 100 corporates, and each leaf contains seeds,” says Ray, whose venture, since its launch in 2014, has expanded to making seed pens, seed pencils, visiting cards and price tags.

Jalebi, launched in Mumbai in December 2014, makes waterproof notebooks, among other organic stationary products. Made in Indonesia, the paper of these notebooks is made from waste plastic bottles and mining waste. Founder Renuka Shah’s aim is to get into eco-friendly and sustainable packaging.

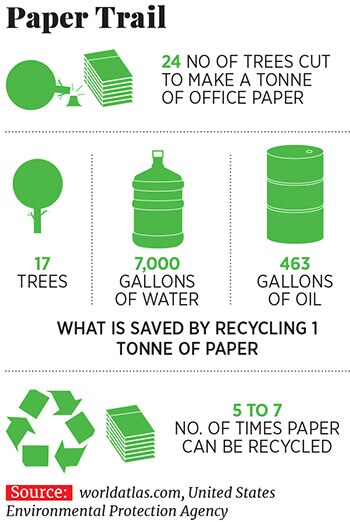

Another venture Pepaa (formerly known as Plantcil), was co-founded by Divya Shetty and Vishnu Vardhan, after Shetty saw her grandfather take his own life, burdened by debts. This made her want to work for the farming community and eliminate middlemen. The duo quit their IT jobs and co-founded Indian Superheroes, a Coimbatore-based venture that creates networks of organic farmers. Shetty also realised that stationery is a water-guzzling sector, contributing to water scarcity. “We cut down about 8 million trees every year to make around 2 billion pencils,” she says.

Another emerging player in the industry is BioQ, started by Saurabh Mehta, who joined his father’s business of disposable ball-pens two years ago. After witnessing the plastic waste generated by the company, Mehta started a sustainable venture, BioQ, in 2018, in Delhi.

“The culture in using stationery is use-and-throw. With seeds inside them, you can sow them and they will grow,” he says. BioQ, which makes pens, pencils and paper, and is coming up with pens that have just 5 percent plastic. By October, Mehta wants to make pens with zero plastic.

While eco-friendly pencils cost almost the same as wooden ones, seed pencils cost ₹20 to ₹25, depending on the seed used. Product margins for sustainable stationery is between 25 to 40 percent. “We don’t keep very high margins, because that defeats the purpose of the product [to make it mainstream],” says Ray.

Mehta agrees. “Since recycled paper is cheaper than wood, the product has the potential to be cheaper. Virgin plastic is ₹100 per kg and recycled paper is ₹30 per kg. The material is cheaper but the processes involved is slightly more expensive,” he adds.

Manufacturers, however, face the challenge of convincing consumers, given the lack of awareness around these products.

The cost of selling sustainable stationery is higher due to low volume, which adds to the constraints of selling it across India. Seeds are expensive too. For example, basil and marigold seeds cost ₹5,000 to ₹7,000 per kg, while imported mint seeds cost between ₹2000 and ₹20,000. Also, while the younger generation is more accepting of rough, handmade paper, older consumers don’t easily adapt to the change.

Mehta believes plantable pencils are a short-lived trend because seed-based products might not see too many repeat customers: “That’s why we focus on other innovations,” he says.

Increasing awareness around sustainability provides hope for players in this industry. At current prices, sustainable stationery is making in-roads and finding niche buyers who can afford it. But given that India is a price-sensitive market, sustainable stationery could see widespread adoption if manufacturers are able to bring price them at the same level as conventional products.

First Published: Jun 13, 2019, 08:07

Subscribe Now