Finding Christmas in Books: Calcutta, Little Women, Harry Potter

Few festivals have been as meaningfully captured in literature as Christmas, as you will find in this eclectic selection

Army shoes for Marmee

One of the most memorable opening scenes in Christmas literature is the one in Louisa

M Alcott’s classic 1868 novel, Little Women:

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,” grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.

“It’s so dreadful to be poor!” sighed Meg, looking down at her old dress.

“I don’t think it’s fair for some girls to have plenty of pretty things, and other girls nothing at all,” added little Amy, with an injured sniff.

“We’ve got Father and Mother, and each other,” said Beth contentedly from her corner.

In a few brisk lines, Alcott not only apprises us of the March sisters’ less-than-affluent circumstances but opens little windows into their personalities: Joe’s a good-natured grumbler, Meg seems acutely conscious of being poor, Amy is jealous, and Beth virtuous. Beth’s quiet admonishment—a nice spot of greed shaming—hushes the grumbling. The sisters are immediately reminded that Father is away fighting in the American Civil War, and Mother, whom they call Marmee, is out working hard to keep the family fed. As the girls warm her worn slippers before the fire, they decide to pool their meagre Christmas money to buy gifts for Marmee instead of indulging themselves. And so Meg buys her gloves, and Joe a pair of army shoes. Beth’s contribution is “handkerchiefs all hemmed”, and as for Amy—she initially buys a small bottle of cologne after secretly keeping back some money to buy herself coloured pencils, but feels so guilty about it on Christmas morning that she exchanges the tawdry bottle for a “handsome flask” of cologne. Amy’s tussle is a nice touch—she’s a little girl after all. Even big-hearted Joe feels a pang when she wakes up to see no stockings hung at the fireplace. But it’s a fleeting pang and Marmee’s joy makes their sacrifice worth it. Alcott’s exquisitely restrained description of Marmee’s reaction —she “smiled with her eyes full”—demonstrates what a fine novelist she is. The addition of one more word, the obvious ‘tears’, would have ruined that brimful line. Instead, its shimmering absence throws the Christmas tableau of the March family into bittersweet relief.

Image: Sucheta Das / Reuters

Image: Sucheta Das / Reuters

Burra Din on Park Street

No city in India is infused with that magical Christmas-y feel as Calcutta is—an inheritance from its tenure as the longtime capital of British India. The celebrations of Burra Din, as Christmas was and continues to be known in this city burdened with culture and chaos, is lingeringly evoked in Calcutta, Amit Chaudhuri’s collection of essayistic meditations.

The Calcutta-born and Oxford-educated Chaudhuri is one of India’s most delicate writers. His unusual memoir has a solemn, oblique intimacy, frequently punctuated with eruptions of enthusiasm for aspects of the city he loves—chief among them, Christmas—and eruptions of peevishness for things he hates—chief among them, Christmas pudding. “Until, say, 1969, Calcutta had the most effervescent and the loveliest Christmas in India—probably I’d hazard, based on my experience later of Christmas in England, the loveliest in the world,” writes Chaudhuri. Why 1969? That’s when the “emergence and crushing of the Naxalites” changed Calcutta as it did “Christmas on Park Street”.

Though things may not be quite the same, Calcutta retains its quotient of Christmas cool. The legendary Park Street tearoom, Flurys, continues with its special Christmas menu and streamers, and one shares Chaudhuri’s childlike delight in spying a man on Free School Street, “carrying a large cotton wool beard and an immense red suit: bits that would coalesce at some point into a figure of Santa”. Most droll of all is the Anglophile Bengali custom of Christmas lunch at the Bengal Club, with its antic menu of “fish buried under almond sauce roast ham with a sort of dark twinkling lacquer veneer turkey, of course, most unexciting of meats… Christmas pudding in brandy cream”. This very club, Chaudhuri ruefully notes, once had a ‘Dogs and Indians Not Allowed’ sign, and still insists on a jacket-and-tie dress code for formal lunches, which he gamely abides by, because, as he quickly adds, the weather is nippy enough to justify a suit.

The enthusiastic refrain that runs through this whimsical book is that the most “paradisial time” to visit Calcutta is in the seven-day run-up to Christmas.

Surprise! Oh, No!

The American short story writer O Henry was an entertainer par excellence, addicted to surprise endings and emotional plots. Sentiment and surprise form the warp and weft of his most popular short story, The Gift of The Magi. The title harks back to the three wise men known as the Magi, who travelled to Bethlehem to pay their respects to the baby Jesus. Guided by a moving star, they came bearing gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

O Henry’s story, set in the early 1900s, is about a newly married New Yorker couple, Jim and Della Dillingham, whose love for each other is as rich as their bank balance is poor. They live in a flat as shabby as Christ’s manger, and are so hard up that Della is forced to haggle with the butcher until her cheeks burn with shame. Desperate to buy each other Christmas gifts that count—not something rubbishy and namesake but something “fine and rare and sterling”—they sell their most prized possessions: Della her shining, rippling, knee-length, brown hair, and Jim, the handsome gold pocket-watch he has inherited from his grandfather. Now they have enough cash to buy each other a proper gift. But on Christmas morning they realise with stabbing dismay that their gifts are perfectly useless. For Della has bought Jim a platinum fob chain for his watch and he has bought her a set of bejewelled tortoiseshell combs for her hair.

One feels terrible for this rash young couple, but O Henry softens the blow by reminding us these “two foolish children” are actually quite extraordinary for valuing love above material wealth. He ends his rueful comedy with an uplifting homily and one can’t agree more when he says: “But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the Magi.”

Mrs Santa Claus

Father Christmas gets all the good press. Kids adore him, the market loves him, and the media does too. Why won’t they? He moves merchandise and makes cash registers jingle. Which is all very well, but what about hardworking Mother Christmas? While Father Christmas is handing out gifts and getting brownie points for being such a jolly feller, Mother Christmas gets not a word of thanks for actually trudging to the big bazaar to buy and then wrap those countless gifts. It’s suspiciously like the Mum-Dad dynamic in most homes. But Roald Dahl is having none of it. The children’s writer who gave us Charlie and the Chocolate Factory sets the record straight in a punchy little poem called Where art thou, Mother Christmas? It’s short enough to reproduce in full, so here it is, with apologies to Father Christmas who gets treated rather roughly for being a slacker:

Where art thou, Mother Christmas?

I only wish I knew

Why Father should get all the praise

And no-one mentions you.

I’ll bet you buy the presents

And wrap them large and small

While all the time that rotten swine

Pretends he’s done it all.

So Hail To Mother Christmas

Who shoulders all the work

And down with Father Christmas,

That unmitigated jerk.

Not Curmudgeonly Enough

Okay: We all know Christmas is the season of fellowship and family and tra-la-la-la. But what if you’re sick of the whole festive caboodle, the forced cheer, and the tra-la-la-la? And what if you could escape it all? That’s the delicious, guilty thought that creeps into the minds of Luther and Nora Krank, the retired couple starring in John Grisham’s schmaltzy and mercifully slender novel, Skipping Christmas. Their only daughter is in Peru, and without her it’s going to be a drudgery to get through the season. The Kranks book themselves on a Caribbean Cruise and salve their conscience by donating $600 to a children’s hospital. So far, so curmudgeonly. Except that their neighbours are so outraged by their attitude, they stage a dharna around their lawn, urging them to get with the holiday spirit. When the local rag runs a story about their mean-spiritedness, Nora begins to cave, but Luther stands firm. Then their daughter calls to say she’s coming home and bringing her Peruvian fiancé with her. Bang go the cruise plans. The Kranks rush around madly to buy a tree and get the house kitted out in red and green, assisted by the busybody neighbours who are so delighted at their change of heart that all is forgiven. After this, things get steadily more saccharine, so we’ll stop here.

What on earth compelled the master of courtroom drama to write a second-rate Christmas caper with a plot as thin as tinsel and as predictable as punch? It’s a dark mystery, but one fervently hopes that in the future Grisham sticks to murder and skips Christmas for good.

Red and Blue with Cold

Hans Christian Andersen, that big, bony, fairy-tale genius from Denmark, often wrote stories with sad and even cruel endings. Among them is his Christmas classic, The Little Match Girl. It’s a heartbreaking tale about a child vendor who walks the streets bareheaded and barefooted, trying to sell matches that she carries in a bundle in an old apron. We meet her at the end of a long, hard day when she hasn’t managed to sell a single matchstick. She’s hungry, and her tiny feet are red and blue (not quite the Christmas colours) with cold, but she daren’t go home for fear her father will beat her. So she curls up against a wall and lights one match and then another to keep herself warm. She begins to have visions of a table loaded with a roasted goose and of a tall Christmas tree spangled with lights and ornaments. And then her beloved grandmother appears in a radiant glow and takes her to heaven where there is neither “cold, nor hunger, nor anxiety—they were with God”. The next morning, the townspeople find the match girl “with rosy cheeks and with a smiling mouth, leaning against the wall—frozen to death”.

Child poverty and hunger were widespread in 19th-century Europe—the inspiration for this story was a calendar picture of a child selling matchsticks. Andersen, who grew up in the slums of Odense, has tasted want, and it scarred him. He uses the prosperity associated with Christmas as a foil to highlight the inequality around him. This is a hard story to read because it cuts so close to the bone, reminding us piercingly of the squads of children selling Santa caps, flags, jasmine garlands and assorted trinkets at the traffic lights and on sidewalks—the little match girls and little match boys of our cities.

Toothpicks and Invisibility Cloaks

Harry Potter makes it to this list for two reasons: For getting the worst and best Christmas gifts —ever. And for the curious way in which JK Rowling imports a Muggle festival into her wizarding world. First, the gifts.

The worst Christmas gifts Harry receives are from his odious relatives, the Dursleys, who, on successive Christmases, give him dog biscuits, a fifty-pence piece, a toothpick, and finally, a tissue. It’s just as well that he gets the best Christmas gift in history: An invisibility cloak, made of a material that looks like woven water. When he tries on the “fluid and silvery gray” shroud, he disappears from sight. The fact that the cloak was owned by his father, who was killed by the evil Voldemort, makes it even more precious.

More intriguing, however, is the fact that wizards celebrate Christmas. Rowling (who describes herself as a questioning believer) achieves this by secularising the festival. She Christian-proofs it, so to speak. The birth of Jesus is never mentioned—it’s almost as if an invisibility cloak is thrown over it. While other Muggle concepts like money are a novelty in the magic world—Harry’s friend Ron Weasley has never seen a fifty-pence piece—Christmas is evidently very much part of the calendar. The Great Hall at Hogwarts is strung with lights, wizard carols are sung, there’s eggnog, and even a traditional Yule Ball (Harry’s date is Parvati Patil). Despite unmooring it from its religious roots, Rowling retains the emotional cargo and moral lessons of the festival, with its stress on generosity and the importance of family. The orphan Harry feels the lack of family acutely, though his misery is greatly alleviated when he is embraced by the Weasleys—an impoverished, happy family plucked straight from the lachrymose world of Dickens.

A Raj Celebration

In 1886, when he was a young, successful, and rather cheeky journalist in Lahore, Rudyard Kipling wrote a poem called Christmas in India, describing what it felt like for the British to be away from home during the festive season. Instead of the traditional holly, mistletoe, and roaring fires, the officers have to make do with skies of “saffron-yellow”, parrots, conches, cattle, and dusty tamarisks. The difference in setting and mood is heightened by a Hindu funeral procession passing to the ghat with shouts of Rama—a sobering memento mori that in the midst of birth is death. All this sounds rather grim. But Kipling was sharp enough to discern that the sahib’s homesickness was a bit of a pose, and he parodies the way the colonials pine for “Home” while “Home” scarcely registers their absence:

They will drink our healths at dinner—those who tell us how they love us,

And forget us till another year be gone!

Isn’t it better, then, to set aside dutiful nostalgia and make the most of an Indian Christmas? If it’s really that difficult, he adds sardonically—implying it isn’t—well, at least one more Christmas will be over and done with:

Let us honour, O my brother, Christmas Day!

Call a truce, then, to our labours—let us feast with friends and neighbours,

And be merry as the custom of our caste

For if “faint and forced the laughter,” and if sadness follow after,

We are richer by one mocking Christmas past.

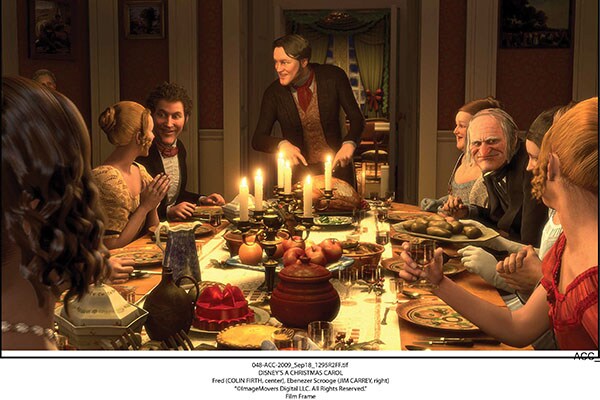

Image: Courtesy ImageMovers Digital LLC

A timeless tale: In a review of A Christmas Carol, William Makepeace Thackeray, a contemporary of Charles Dickens, wrote: “It seems to me a national benefit, and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness.”

The Story That Invented Christmas

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens is, of course, the classic Yuletide story—the story that invented Christmas as we known it today, a festival of gift-giving and communal joie de vivre. Or, in the less effusive words of the late atheist Christopher Hitchens, we owe “the grisly inheritance that is the modern version of Christmas” to Dickens.

The tale itself is stocked with all the necessary ingredients of redemption: A bitter, old miser, Scrooge, is visited by a succession of ghosts who give him the fright of his life and make him repent his hard-hearted ways the tear-jerking presence of a poor but loving family in the form of the Cratchits and the happy ending amidst glorious lashings of food, sponsored by Scrooge, now that his purse-strings have been loosened.

An unabashed sentimentalist and social reformer, Dickens wrote this story at a time when hunger stalked through England. It was meant to prod his countrymen’s conscience, and prod it it did. Published on December 19, 1843, it was an instant best-seller. And one has to only read his unsparing description of Scrooge to see why. Here is Dickens at the top of his game: “Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster... He carried his own low temperature always about with him he iced his office in the dog-days and didn’t thaw it one degree at Christmas.”

This story has also lent us two of the most memorable phrases in literature. The first is Scrooge’s disgusted exclamation at all things Christmas-y, “Bah! Humbug!” (this is before the ghosts show up), and the second is the piping benediction delivered by the Cratchits’ young and ailing son, Tiny Tim, which, in its democratic embrace, captures the true spirit of Christmas. And so, Merry Christmas to one and all, and in the immortal words of Tiny Tim, “God bless us every one.”

First Published: Dec 23, 2014, 06:28

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Mar 19, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)