Mira and the movies of life

Though she draws from the street to tell stories that endure, Mira Nair calls herself a shameless populist who doesn't want her movies to be homework. With her acclaimed Monsoon Wedding soon to hit th

Image: Andrew H. Walker / Getty Images

Mira Nair has a gift for us. It won’t be ready until May next year, but she promises it’s worth waiting for. “There are 21 songs. And the tent is a big character,” she tells ForbesLife India over the phone from New York. The story won’t be the same as the original but there will be a few famous scenes from it. “The music, brilliantly composed by Vishal Bhardwaj, will propel the plot and everything else.”

The gift, you ask? Two words: Monsoon Wedding. Or make that four: Monsoon Wedding, the musical.

Nair is on course to open the production at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre in early summer 2017, slowly moving it to the New York stage by fall. The casting is near done, and the excitement in her voice underscores how this is a labour of love. Much like the movie.

Fifteen years after the colourful story of a family wedding was released to high praise, its charm continues to endure. “In Monsoon Wedding (2001), it’s really the madness of my family table that you see,” says Nair. While the joy of an Indian wedding was celebrated, the movie also probed the murkier secrets and realities of families, giving the audience a window into their own lives. “People recognised themselves in it,” she offers.

And now, the 59-year-old filmmaker is “deep into the process” of reshaping it for stage, her first love. “The stage version is modernist, and yet doesn’t lose any of its punjabiyat,” she says with the ready laugh that punctuates her conversation, and makes me wish the journey from Mumbai to New York was less prohibitive.

Oh well, it is what it is, and I have Nair on the phone. A slightly exhausted Nair post her Queen of Katwe release frenzy, but engaged and chatty nonetheless.

I tell her that I’d re-watched Monsoon Wedding before our interview, and not really as homework. And not only did I recall how much I had enjoyed it the first few times I had seen it, it was also a reminder of Nair’s pre-eminence as a storyteller. After all, though weddings have inspired Indian movies for generations, the relatability of Monsoon Wedding—in both its festive fervour and gloom—is universal.

But then, finding stories where others may not think to look is Nair’s tour de force—be it in the slums of Mumbai or the shanty towns of Kampala, Uganda, where she spends half the year with her husband Mahmood Mamdani, a professor of anthropology. For part of the year, he teaches at New York’s Columbia University, where Nair, too, is an adjunct professor of film. “For me, authenticity and truth have always been infinitely more powerful or stranger than fiction,” she says. “Genius is everywhere, we just forget to look.” Mira Nair’s latest film, Queen of Katwe, is a real-life tale of an impoverished girl in a Kampala slum who becomes an international chess master

Mira Nair’s latest film, Queen of Katwe, is a real-life tale of an impoverished girl in a Kampala slum who becomes an international chess master

Her latest movie, Queen of Katwe, resonates with that message. “Because I live in Kampala [Mamdani is Ugandan], Queen of Katwe is made with a completely insider’s view of how it really is. Of how the practice of living is, despite the struggle,” says Nair. The inspirational real-life tale of an impoverished girl who became an international chess master was shot in Katwe, a harsh slum, where the champion found her calling. “Even Ugandans have not seen Katwe as we have portrayed it,” says Nair.

This ability to transform the real into cinematic marvels has given Nair her biggest successes. Salaam Bombay! (1988) followed the trials and triumphs of life in Mumbai’s slums The Namesake (2006) articulated an Indian immigrant couple’s attempt to build a home in America the racial divide between blacks and browns flowed through Mississippi Masala (1991), and, of course, there was Monsoon Wedding. Not only have these films won awards and critical acclaim, they have also drawn in diverse audiences cutting across geographies and communities. “The key thing in this day and age is how to remove the other. How to remove the notion of any one of us being the other,” she says. “What I am so heartened about Queen of Katwe is that people are receiving that [message], that my street is so much like your street.”

Most of these movies follow the classic coming-of-age arc while addressing the complex questions of race and class. As Nair says, “I remember for Mississippi Masala, the lines around the block [to enter the theatre] were largely inter-racial or mixed people. It [the movie] was radical in the ’90s. Now, it’s different. Now there is a real constituency and a much bigger awareness of the vocabulary that I put up on screen. And if these people are waking up, in terms of the screen reflecting that diversity, it’s interesting to not be as lonely as I was when I began with Mississippi Masala.”

Loneliness, though, is often a companion to unconventionality. And Nair has never been one for the tried and tested. As her old friend and former HSBC India chairman Naina Lal Kidwai, who met Nair at Loreto Convent Tara Hall in Shimla when they were in their early teens, reminds me, “This was in the 1970s. At the time, if you look at the way we were, it is remarkable how she wasn’t worried about breaking conventional barriers.”

Academically bright, Nair’s proclivity for the arts was evident from the start. “In terms of her literary skills, I had no doubt she would be somewhere,” recalls Kidwai, adding that Nair would “even bully” them to write for the college magazine she had started. “I didn’t know what shape it would take, but her interest and ability in theatre was clear.” Two years into college at Delhi’s Miranda House, Nair got a scholarship to study Visual and Environmental Studies (essentially filmmaking, she says) at Harvard she was also accepted by Cambridge University. She chose Boston. “I had seen it in Love Story,” Nair has said in various interviews.

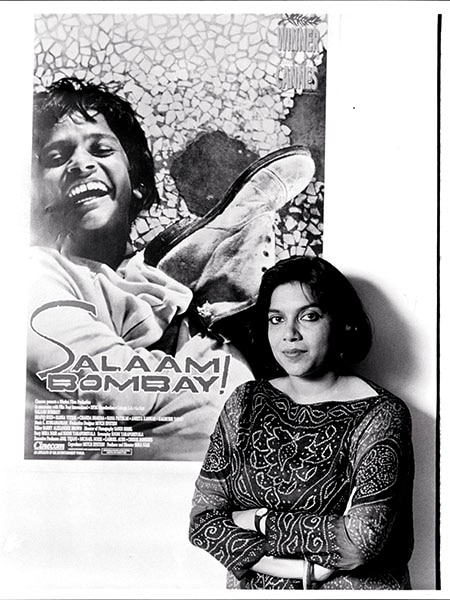

At 19, not only would it have been difficult to make a life for herself in America, points out Kidwai, but she was also determined to enter the movies.  A young Nair with the poster of her first fiction attempt, Salaam Bombay!, which went on to get an Oscar nomination in the foreign language category in 1989

A young Nair with the poster of her first fiction attempt, Salaam Bombay!, which went on to get an Oscar nomination in the foreign language category in 1989

There is a heartfelt sigh before Nair admits how getting a foothold in cinema was, in fact, “gruelling”. “My god,” she says, “the self-motivation and the loneliness of it! Though I must say, I am deeply grateful to have been allowed to find my path. I had this scholarship to go abroad when I was 19, to discover cinema at 21, to discover cinéma-vérité, the cinema of life.” Working on documentaries—Jama Masjid Street Journal (1979), for her thesis for Harvard, and So Far From India (1983)—by embedding herself in those settings set the tone for her future film-making.

Consider how she sat on slum pavements in Mumbai with her friend and screenplay writer Sooni Taraporewala to study the children whose stories they were going to tell in her Oscar-nominated movie. “I had never studied fiction till I made Salaam Bombay!. So to discover cinema which was not understood, certainly not by my family, certainly not by my society in India… those were tough but interesting times, and also established one’s own tenacity—one’s own craziness. My nickname is Pagli for a reason: I am mad!”

What she calls madness, Kidwai describes as vision. “It is more the ability and vision to look forward.”  Monsoon Wedding won the Golden Lion for Best Film at the Venice Film Festival in 2001. Nair says she was inspired by Sooraj Barjatya’s Hum Aapke Hai Koun..!

Monsoon Wedding won the Golden Lion for Best Film at the Venice Film Festival in 2001. Nair says she was inspired by Sooraj Barjatya’s Hum Aapke Hai Koun..!

Image: Getty Images

That vision pushed her towards her method, her process. Like living with cabaret dancers for months for India Cabaret, her third documentary (1985). “My family did not know what to do with me,” she laughs. But, she says, “It’s good to be able to find your way without constant pressures, which, of course, I was feeling. Shaadi karo [get married] and all of that. Sab saha humne, but kaam kiya [I suffered through it all but I worked]. I’m still doing the same damn thing, something new each time. But it’s essentially the same struggle. What to say about the world, how to say it, and then how to con people into letting

me say it.”

One reason Nair doesn’t need to do much conning anymore, and is, in fact, courted and feted as a mainstream director despite her off-the-beaten-path choices is because she doesn’t consider the authentic to be boring. She is even appalled at the notion of her films being considered “homework”. “I really think of myself as a shameless populist. I like to put bums on seats, I like to have the people come who want to watch the film, and not just because I am authentic. That would kill me!” she says. “The colour, the sexuality, the humour, all those things are part of my world. I don’t think of financial success but I think of movies as designed for selling tickets. It has to be successful in reaching people, and making them think a little bit anew about the world and about themselves even.”

On that count, Monsoon Wedding was a triumph. It was among the top 10 all-time highest grossing foreign films in America at the time of its release. Her acclaimed adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake also drew in the crowds.  Tabu, who Nair cast in The Namesake, credits the filmmaker with giving her international acclaim she also reveals the extent of Nair’s love for yoga. “Mira has a clause in her contract that she should be provided with an Iyengar yoga instructor on sets. So, before shooting [The Namesake], we would do yoga for an hour every day!” the actor says

Tabu, who Nair cast in The Namesake, credits the filmmaker with giving her international acclaim she also reveals the extent of Nair’s love for yoga. “Mira has a clause in her contract that she should be provided with an Iyengar yoga instructor on sets. So, before shooting [The Namesake], we would do yoga for an hour every day!” the actor says

Image: Carlo Allegri

Tabu, who acted in the film as Ashima, the Bengali girl whisked off to the US by her husband Ashoke Ganguli (essayed by a Nair favourite, Irrfan Khan), points to Nair’s ability to “say the most serious of things in the most entertaining manner”. “Her films are not drab and boring although her subjects/storyline may be serious, she knows how to say things commercially, in an interesting way. She has that pulse. She has a fantastic sense of humour. She’d tell me on the set, ‘Tabuji, abhi toh aapke saath item number karna hai!’”

However, Nair, who has seen her share of criticism and commercial failure—such as with her adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Victorian classic Vanity Fair in 2004 and the ill-fated Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love (1996)—doesn’t dwell on the numbers. Even big-budget movies have been floundering in Bollywood and Hollywood. Scale and opulence do not automatically translate into box office billions. “No one has found a formula for financial success, thankfully,” she laughs. “I must tell you that I don’t think of it at all when I am making something. The thing that I do think about is whether I want to be in that world. For a couple of years before presenting it to you, it must obsess me, it must interest me, delight me, trouble me.”

Evidently Harry Potter didn’t do that for her—she famously turned down an offer to direct a movie for the franchise. In fact, nothing delights, troubles and obsesses her as much as India. That, at least, is the popular view. Former President Pratibha Patil awards Nair the Padma Bhushan, India’s third-highest civilian award, at Rashtrapati Bhavan in 2012

Former President Pratibha Patil awards Nair the Padma Bhushan, India’s third-highest civilian award, at Rashtrapati Bhavan in 2012

Image: Getty Images

Rajat Kapoor, who essayed the role of an abusive uncle in Monsoon Wedding, says, “I think there are films which really come from her heart. I think Monsoon Wedding is one of them. The Namesake is another that I’m really fond of. So is Salaam Bombay!. I feel like every time she comes back to India or makes a film about Indians, it really works well.”

Africa and the US are now her stomping grounds, but India is where she finds her mojo. “She may have lived outside India for the last 30 years,” says Kapoor, “and I’m sure she has many identities, but something extra happens with these films. It’s intangible, you know. You can’t put a finger on it and quantify it. I very strongly feel that The Namesake is so moving because it finds some inner truth within her.”

During her chat with ForbesLife India, Kidwai, too, singled out Nair’s India-based films. “My favourite ones are always about Indians in a global setting. These come from a very unique life that she herself has led, deeply anchored in India and the US, and now increasingly in Africa,” she says.

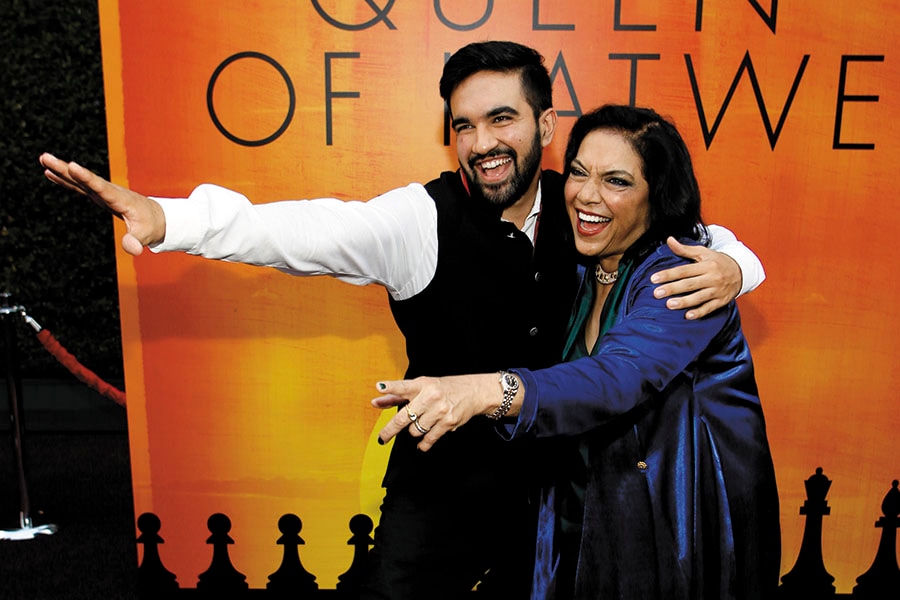

Perhaps it is because some stories are better when told from the inside. Like Monsoon Wedding, which, Nair says, “was told by Sabrina [Dhawan] and myself with knowledge, great irreverence and love”. The simple, marigold-laden wedding in Delhi may have been a far cry from the grandeur of the “21-song version of a shaadi” that Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (HAHK, 1994) was, but Nair surprises me by saying that she was inspired by the Sooraj Barjatya blockbuster. “I had a great time watching it—the whole family went. I thought let’s make a reality check version, jo asli mein hota hai. But again, me being as I am, I wanted that audience of HAHK. I wanted to reach people and not make a documentary. And, unwittingly, I put my finger on that eternal quality at the heart of what is family, the secrets we share, along with the love glue that we thank our stars for. The punjabiyat!”  Nair with son Zohran Mamdani, who acted in Queen of Katwe

Nair with son Zohran Mamdani, who acted in Queen of Katwe

Image: Danny Moloshok / Reuters

The glue, however, could easily have come unstuck if left to the wrong actors. But she has a knack for finding the perfect fit. In Monsoon Wedding, she collected a motley crew in terms of experience and stardom. The common thread: “The instinct and desire to be with them [the actors],” she says. “I never forget a performance. I saw Naseer [Naseeruddin Shah played the father of the bride] in a play called Zoo Story when I was 17, and I’d been yearning to work with him.”

For Queen of Katwe, Nair knew she wanted Oscar-winner Lupita Nyong’o. “So we wrote the role of Harriet for her,” she says. The movie also features 17 children chosen from the streets of Kampala—and this was hardly the first time Nair had gone talent-spotting on the street. For Salaam Bombay!, she used her friend Kidwai’s downtown apartment on DN Road, Mumbai, to conduct workshops for the street children and other first-time actors, whom she wanted to cast in her movie.

Tabu recalls getting a 2 am call from Nair. “She said, ‘Tabuji, please come and do my film, The Namesake.’ I had no clue where this was coming from. I had partly read the book, and I knew what the character was,” says Tabu. “I told her, ‘Mira, I’d love to do the film. When are you starting?’ I expected her to say six months or so, but she said: ‘In two weeks’. I was shooting for Andarivaadu with Chiranjeevi in Hyderabad then and was also building/setting up my house there. But I was in New York in two weeks. So suddenly from doing a latka-jhatka number in a saree on that set, I was transported to New York.”

Nair’s collaborators revel in her spontaneity. “Now, 16 years after [making] Monsoon Wedding, I can tell you that it was definitely the warmest set ever,” says Kapoor. “I’ve since done many films and never experienced the kind of warmth I did then. And I think it had to do with her personality, with her being, because her own warmth percolated to every last person on the set.” Naina Lal Kidwai (centre) and Nair both participated in theatre at their school, Loreto Convent Tara Hall, in Shimla. Here, they are seen with their old principal Sister Cyril—“who directed all our school plays and was a huge part of our extra-curricular life,” says Kidwai—at The Namesake’s post-premiere party in Delhi in 2007

Naina Lal Kidwai (centre) and Nair both participated in theatre at their school, Loreto Convent Tara Hall, in Shimla. Here, they are seen with their old principal Sister Cyril—“who directed all our school plays and was a huge part of our extra-curricular life,” says Kidwai—at The Namesake’s post-premiere party in Delhi in 2007

Image: Getty Images

Kidwai, whose daughter Kemaya acted in the movie, was a frequent visitor to the set. “It was the first time I saw Mira up front as a director and I was so struck by the fact that she was taking inputs from the actors. Of course, she had the last word! But the way she handled people was quite remarkable,” says Kidwai, who admits to being reluctant about allowing her nine-year-old to take on the role of Aaliya. “Mira will always remind me how I was against it when she popped the question to us. It took the principal of Vasant Valley School [where her daughter was studying] to tell us that we were wrong to not let her do the film.”

That experience, says Kidwai, created memories for her daughter. And built a bond between her and Mira, so much so that when Kemaya went to Yale, Nair’s home in New York was a safety net for her. This has as much to do with Nair’s ability to create a beautiful home as to do with her affinity for family.

Born in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, to a high-ranking civil servant father Amrit, Nair is immensely close to her mother Praveen and two older brothers, Vikram and Gautam. However, she spends most of her time in Kampala.

She is even working with her son Zohran on a television show—“something between Africa and America, quite vast and not seen before,” Nair says. “It should be good.”

What it will be, for certain, is another step towards diversity: Both in front and behind the camera.

As Nair points out, although Hollywood has woken up to the “shocking inequity in terms of women behind the camera”, it is only “just” happening. “There’s organising, there’s mentorship. Pressure has shown a mirror to those who are making movies, to say ‘white men in suits’ are always financing ‘white men in suits’.”

And the issue has always gone beyond gender for Nair. She has long embraced her own identity as a person of colour, and doesn’t shy away from addressing race in the face. “The key thing for me is to mentor. It is to open one’s arms and open the doors. That’s what I have insisted on doing, not just for gender, but also for colour. If I go to South Africa and if there’s a white crew, I would say, no way. We are going to open it up. Not going to submit to this. My crew needs to be mixed.”

To that end, she is also nurturing directorial talent from Africa through Maisha Film Lab, a non-profit training initiative for East-African film makers, set up by her in 2005.  Nair with Kate Hudson and Riz Ahmed during a promotional event for The Reluctant Fundamentalist at the Venice Film Festival in 2012

Nair with Kate Hudson and Riz Ahmed during a promotional event for The Reluctant Fundamentalist at the Venice Film Festival in 2012

Image: Max Rossi / Reuters

It helps that the notion of women in leadership positions was never novel to Nair. As it transpired, we were speaking the day after Hillary Clinton had torn into her political opponent Donald Trump at the final presidential debate. “She did good,” Nair smiles over the phone—and I respond that it is odd that a developed country is still grappling with the idea of a woman president. (The results were in by the time we went to press, and, sadly, America has to wait for at least another four years to break that glass ceiling.)

“The paradox about coming from India is that in the 1960s and ’70s, I grew up seeing women in roles of leadership. Those were the Sushila Nayyar days,” says Nair, invoking the youngest sister of Pyarelal Nayyar, personal assistant to Gandhi. Sushila was Gandhi’s physician as well as health minister in Jawaharlal Nehru’s cabinet (1952-55). “It was not uncommon to have a woman in a leadership role. [For young people], it is powerful to see that it is possible, that women can be in these roles.”

That confidence manifests in her easy embrace of various roles. “As a person, there are so many shades to her,” says Tabu. “At home, she’s the perfect homemaker who cooks amazing biryani on Eid, and serves everyone with that much love and affection. On the set, she is an absolute taskmaster. She’s also a very clued-in businesswoman who knows her deal.”

But no one thinks ‘woman’ or ‘Indian’ when they think of Nair—labels just don’t seem appropriate. And that is an acknowledgement of how seamlessly she has assimilated into the world she now inhabits, and one she looks at through a thoughtful but hopeful lens and plenty of laughter.

Her view of Indian cinema, for instance, is cautiously optimistic. “The sophistication of Indian cinema is just stunning, in terms of what can be achieved by way of technology. There is no longer any need to apologise, like in the olden days. Or even go abroad to finish [a movie]. The technical achievements are deeply noticeable,” she says.

It is “pure joy” for her to see the gamut of independent films like Chaitanya Tamhane’s Court (2015) or Kanu Behl’s Titli (2015) and commercial successes like Zoya Akhtar’s Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (2011) or Dil Dhadakne Do (2015) “which I recently resaw”. What bothers her are the movies—and those aren’t far to seek—which are overblown, made with technical brilliance but, as she puts it, “striving for effect but pleasing no one”.

In her own work, she seeks imagistic inspiration through modern art and photography, which is “like oxygen to me”.

In fact, ask her to name cinematic role models, and she’d rather talk about trees. “To grow things is the only way to evade despair. And trees are where I get my tranquillity.” Perhaps this kinship with nature harks back to a childhood spent in the open fields around Bhubaneswar. Nair has even created gardens in the “slummiest areas” of Kampala. “My father-in-law,” she offers as an example, “was buried in an old cemetery. It was beautiful but trashed, and I took it upon myself to refurbish it.” On her chosen form of foliage, she reiterates, “I’d much rather work with trees than flowers.”

This is no ordinary love.

For emphasis, and lest I mistake her green obsession for jest, Nair starts to talk about a recent “serious health scare” she had. Reassuring me that she is strong now, she adds: “And the last thought I had was how much the trees had given me pleasure.”

Additional reporting by Kunal Purandare and Angad Singh Thakur

First Published: Dec 10, 2016, 06:07

Subscribe Now