The science of being human

The best of science fiction novels redefines the qualities that make us an evolved species

It takes a while to figure out exactly what Isaac Asimov’s ‘Does a Bee Care?’ is about—short though the story is, and simply told, you might need a couple of readings to grasp its full scope. The narrative begins with a man, or a creature that has the appearance of a man, hanging around while a spaceship is being constructed. No one pays ‘Kane’ much heed, but his presence has an effect on some people it stimulates their minds, creating ideas that can have far-reaching consequences.

Eventually we learn that this alien entity had been deposited on earth as a sort of ovum, and that its natural process of maturing required driving a whole planet towards civilisation, so that it could find the way back to its own corner of the galaxy. Driven by instinct over thousands of years, not fully understanding why these things had to be done, Kane lit sparks in the minds of individuals like Newton and Einstein, all with the sole purpose of facilitating space exploration. “Does a bee care what has happened to a flower when the bee has done and gone its way?” is the last line of the story. The flower in this analogy is earth, which has thus been “fertilised”, and the knockout punch is that the things we are so proud of—our capacity for scientific thought, our accumulation of knowledge through centuries—are incidental by-products of the actions of this extraterrestrial ‘bee’.

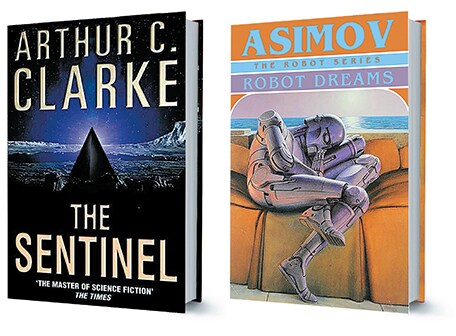

If you have watched Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey, you may see a very fleeting resemblance in the story of the apes in the ‘Dawn of Man’ segment—where a new strain of consciousness is awakened in them by the appearance of a mysterious black monolith. That film was based loosely on an Arthur C Clarke story titled ‘The Sentinel’ (Clarke later developed it into a novel as the film was being made), and anyone who knows science fiction writing of the 1940s or ’50s will know that masters like Asimov, Clarke and Robert Heinlein often took on human hubris and punctured it. They also took special pleasure in pulling the carpet out from under ideas such as patriotism. Most of them did it gently, though, and with humour.

I was thinking about this again with all the talk there has been in India about nation-love, and about showy ways of demonstrating it. Of course, we don’t have a premium on this sort of thing. Consider this quote about NASA’s Pluto mission last year, which came from a White House representative: “I’m delighted at this latest accomplishment, another first that demonstrates once again how the United States leads the world in space.” It’s particularly amusing to see patriotism take a front seat in such a context. Here we are talking about a journey through millions of miles, a vastness that makes any distance between two countries on Earth look insignificant by comparison. Yet we can be parochial even about such achievements!

In Clarke’s story ‘Refugee’, a character reflects how odd it is that shrill nationalism had managed to survive into the space age—a time when the astronaut’s-eye view should have made the artificial geographical divides on our tiny planet appear ridiculous and irrelevant. Others have expressed this thought in different ways. As Carl Sagan put it, Earth when viewed from a long way off is just a pale blue dot, incredibly fragile-looking the sight should humble us, make us feel protective of the little rock we inhabit, and forget about the many divides we have created over the centuries.

Many people think sci-fi deals only with ‘otherworldly’ things, not with important questions about humanity. But actually, this is one of the few genres that can remind us how trifling we are in the larger context of the universe while at the same time showing us the value of our species. The authors I mentioned have all written beautiful stories that demonstrate the best in human nature.

Asimov’s collection Robot Dreams has the incredibly moving ‘The Ugly Boy’, which centres on an organisation named Stasis Inc that has transported a Neanderthal child through time and kept it enclosed in a special centre. A woman named Miss Fellowes is employed to look after the child initially she is repulsed by its feral strangeness, by the largeness of its head, but soon she comes to see it as she would any other lonely infant: “It was a child that had been orphaned as no child had ever been orphaned before. It was now the only creature of its kind in the world. The last. The only.”

What follows is a most unusual bond, one that is headed for tragedy, given the nature of Stasis Inc’s operations but the story ends with Miss Fellowes doing something that will take your breath away even as you realise—if you put yourself in her place—that it was the only thing she could have done. As the author points out in his introduction, the story “is only tangentially about time-travel. What it is really about is love”. This is true of much other writing in the genre.

Among my favourite stories to combine humour with the question of what being human means is Clifford Simak’s ‘Skirmish’ (you’ll find it in the Brian Aldiss-edited anthology A Science Fiction Omnibus, a book I highly recommend). It has a newspaper reporter named Joe Crane—your average Joe—gradually discovering that small, machine-like aliens from another planet are scouting earth with the intention of “freeing” their brethren—the earth machines that are being controlled by humans. The problem for Joe, as he begins to piece things together, is that he alone is in possession of this information and has no tangible proof: If he tried to take it to the authorities, he would be treated as a drunk or a psycho.

You have to read the story to see how he handles this great responsibility that has fallen on his shoulders—and to see how the last line of the story (I can tell you, without any spoilers, that it is “Well, gentlemen? he said”) shows how politeness and etiquette can co-exist with firmness of will, even in very strained situations. That’s one of the things that allows us to call ourselves rational, or civilised.

But as a companion piece to this affirmative story, I would encourage you to read Bertram Chandler’s ‘The Cage’, which offers a more bittersweet view of an ‘evolved’ species. “Only rational beings put other beings in cages,” goes a cynical but true observation in the story. The best of sci-fi shows us how to break the cages we have built for ourselves and for others.

The author is a Delhi-based writer and journalist

First Published: May 31, 2016, 07:58

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 03, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)