Mayfield India's Small, Non-Tech Bets Pay off

Mayfield India’s Vikram Godse and Nikhil Khattau have been turning small investments into big rewards

They say the goddess of wealth showers her attention only over a few, but in Vikram Godse’s case she practically cornered him. On a hot afternoon in August 2009, Godse was supposed to meet Rajesh Lihala, who was hoping for an investment from Mayfield India, the fund managed by Godse and Nikhil Khattau. Godse had a flight to California to catch, needed to pack and had almost left his Nariman Point office in Mumbai when Lihala dashed in just in time.

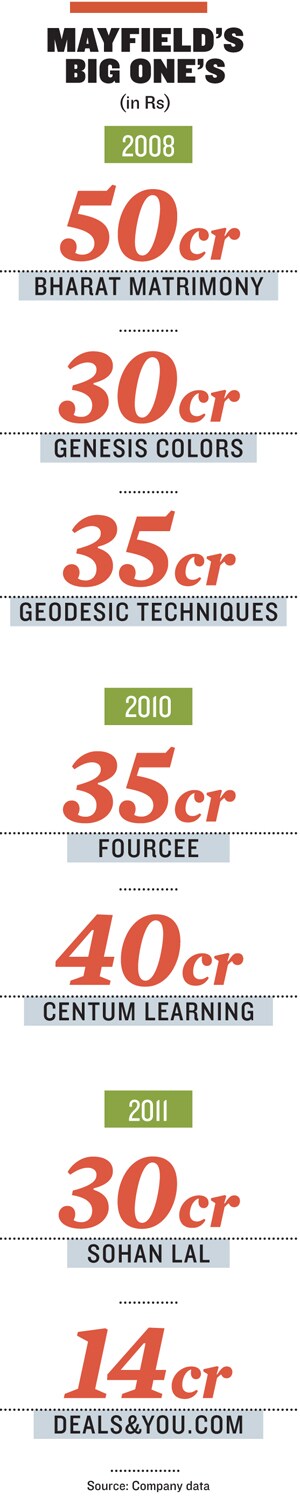

The meeting went on until late evening. Godse did catch his flight, but not before Lihala’s pitch convinced him to invest. Mayfield India put Rs 25 crore into Fourcee Infrastructure Investments in February 2010, when the company’s turnover was hardly Rs 22 crore. A few months later, they added Rs 10 crore. By March 2012, Fourcee had a turnover of Rs 333 crore.

Mayfield sold its entire stake in the company to General Atlantic Partners and earned more than 10 times its original investment price. It proved what Godse and Khattau believe in: If you back an Indian entrepreneur who knows his business, the rewards are great.

In managing Mayfield India’s $111 million venture capital fund, Khattau and Godse seek those rewards using history as their guide, relying on their research to identify sectors and strategies that are tried and true abroad but still evolving in India, letting them get in early on companies likely to succeed. They’re especially focussed on still-small, non-technology companies. “Early stage investing in India is not just about technology investing,” says Godse.

Mayfield consciously looks for companies in the core sector, an area they feel the market has ignored. They believe investors have overlooked 500,000 firms like Fourcee, with good business models but which are short on capital.

That was especially true in December 2008, when Mayfield started investing. The market was still weak after the Lehman Brothers debacle and small businesses were finding it difficult to get seed funding. Khattau and Godse understood that with a little help, these companies could really scale up.

Their investments now include Geodesic Techniques, India’s leading designer and builder of steel frame structures, Sohan Lal Commodity Management, which specialises in agriculture and commodities logistics, Bharat Matrimony, the world’s largest marriage portal, and Centum Learning, a leader in training and skill development programmes promoted by Bharti Group.

Many Mayfield investments address “pain points” in the economy, like Fourcee, which helped companies cut costs by 30 percent. Its success inspired them to look at other cost-cutting companies, and led them to Sohan Lal, a private sector agricultural warehousing company that created customised solutions to help clients cut down on waste and lower logistic costs.

“This was one company that was using complex systems and processes for a warehousing facility and it was showing results. We were clearly impressed,” says Khattau, who is on the company’s board.

He’s particularly interested in finding promoters in the agriculture, insurance and finance sectors. It is tough to find the right ones, but Mayfield has figured out the process.

One and One Make a Team

Godse and Khattau launched the Mayfield India fund in 2008, as part of the Mayfield Fund, a global venture capital firm managing $2.7 billion. Even before Mayfield, they’d had success with similar investment strategies and small companies. Godse had been doing $20 million to $30 million deals as a founder of JM Financial Investment Managers, but the space was crowded. He realised the real opportunity was in earlier stage $4 million to $5 million venture investments.

Prior to JM, Godse invested in Brainvisa, an e-learning company, and Indiagames, a wireless media company, at one of India’s earliest venture capital funds. By 2005 he had exited Indiagames at 14 times the investment. He later joined Cisco’s investment arm and invested in Comviva, a Bharti Group company.

Godse has stuck with companies and trends that he spotted at an earlier stage. When he joined Mayfield, his relationship with the Bharti Group let him invest in Centum Learning, a company with similarities to Brainvisa. He also backed Genesis Colors, which owns the Satya Paul brand headed by Sanjay Kapoor, whom he’d known since his JM days.

Khattau had been investing similar sums on his own. He went solo after selling Sun F&C Asset Management (a private sector mutual fund he founded with $350 million in assets at its peak) to the Principal Financial Group in 2004. While looking for early-stage non-tech companies, he came across Indo Schottle, an auto component manufacturer from Pune that made small but critical high-precision valve components.

It was 2004, when India-China comparisons were common, and Khattau realised India was in a position to incubate companies with quality, while China concentrated on volumes. Three years after Khattau invested $5 million in the company, he sold his stake to Tata Capital for double the price.  Same view, different paths

Same view, different paths

Even though Khattau and Godse share an investment philosophy, their backgrounds are quite different. Khattau came from a typical upper class Mumbai background. He was the head boy at his school and a national-level swimmer. A natural athlete, he’s also completed a triathlon.

He started investing at 19 and joined JM Financials in the late 1980s, specialising in analysis. He later completed his chartered accountancy in London.

Godse, in contrast, went to King George, a middle-class school in Hindu Colony, Mumbai, with a Darwinian ecosystem where only the fittest survive. He completed a management degree from Mumbai University. The son of an ex-Air Force officer, Godse loves the high life but keeps a low profile.

But their approach to investing is similar. They got early experience with JM, and both spend a lot of time on the road meeting vendors, consultants and customers. They like to take to the field themselves, one of the reasons why they work with only two analysts.

“Vikram and I had long conversations about everything. This included our philosophy on investing as well as life. We wanted to be absolutely sure that we were on the same page before we started investing,” says Khattau.

THE MAYFIELD STRATEGY

When Khattau and Godse drafted their investing plan, they decided to focus on sectors that have evolved elsewhere but are still developing in India. India today, in terms of development, is where the US was in the early part of the 20th century, where the UK and rest of Europe were in the 1960s and where China was in the 1990s, they say. So, entrepreneurs and investors can benefit from discontinuous growth by looking for successful models abroad.

One of the key financials Khattau and Godse examine is a business’s capital efficiency. Since early-stage investors have little basic research to go on, both Khattau and Godse meet promoters and evaluate their business models. They also serve on the board of companies Mayfield invests in.

“Mayfield’s philosophy is to invest in relationships, not just transactions this is what I also personally believe in. If people understand each other and believe in relationships, the path to success is bridged easier. They also provide a sounding board to the company when required and lend their experience in various fields to understand businesses better,” says Sanjay Kapoor, who plans to take Genesis Colors public in the next three years.

Finding good people is not easy, but Godse and Khattau are ready to work hard. As the economy becomes challenging, they are looking at sectors like agri business, insurance and low-cost housing finance companies.

Things are not going to be easy. Competition is growing, and there are too many funds chasing the same companies. “But we are one of the few who go much earlier, thereby funding the entrepreneur before others and investing in them ahead of the curve on the back of our own primary research,” says Godse.

First Published: Jul 19, 2012, 06:05

Subscribe Now