Novartis: Innovating for the world, from India

How Vasant 'Vas' Narasimhan is readying India to play a bigger role in its medicines pipeline as the company becomes a pure-play innovative firm

In the world of big pharma, Vasant ‘Vas’ Narasimhan is most certainly an exception.

The son of Indian immigrants and a doctor by training, Narasimhan is the only CEO of Indian origin among the world’s top 20 pharmaceutical companies by revenue. He has also had a long tenure at the helm of a big pharmaceutical company and at 47, makes him the youngest among his peers.

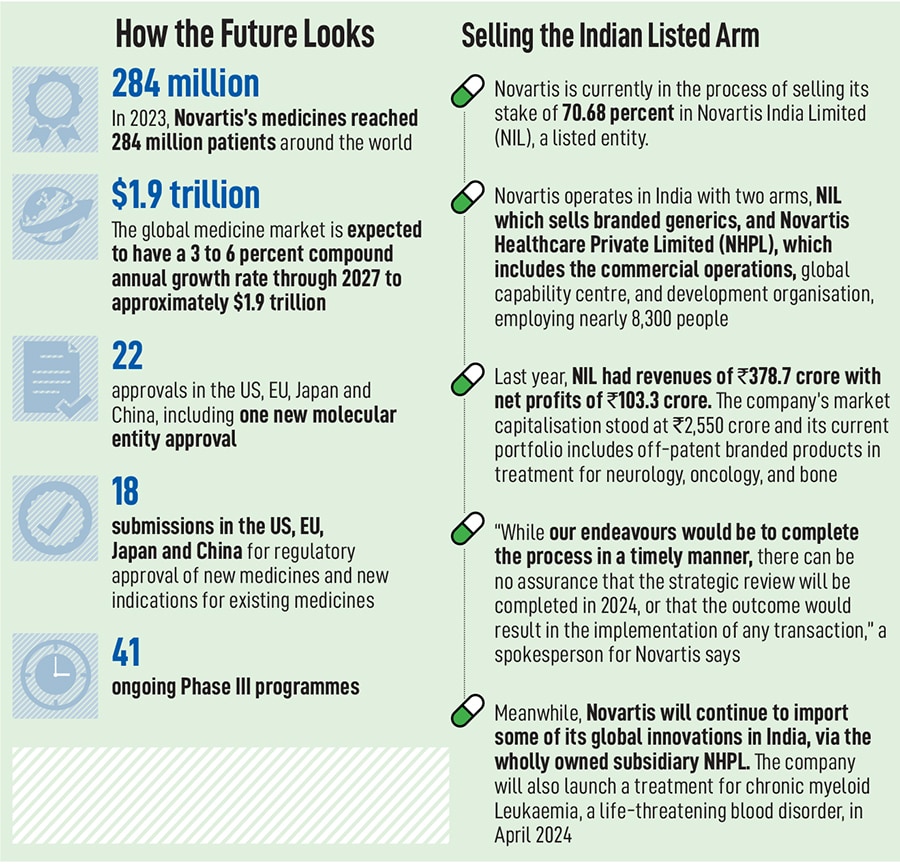

But, more importantly, Narasimhan is also the only one among his compatriots who comes from a research and development (R&D) background in the sector. That’s precisely why since he took charge of the $210 billion Switzerland-based Novartis seven years ago, Narasimhan has pivoted the company from a diversified conglomerate with interests in eye wears, generic medicines and consumer medicines into a pure-play innovative medicines company.

That has meant a sharp focus on five therapeutic areas, with a slew of medicines and technology platforms intended to drive growth in the coming decades. Novartis, which once had as many as seven different arms, today operates a single arm, with the last of its subsidiaries, a generic business company, being sold off in October last year.

“Sector-wide, there’s been a recognition that it’s difficult to allocate capital efficiently across different segments of health care and fully invest in the R&D opportunity within innovative medicines," Narasimhan tells Forbes India during an interaction in Hyderabad.

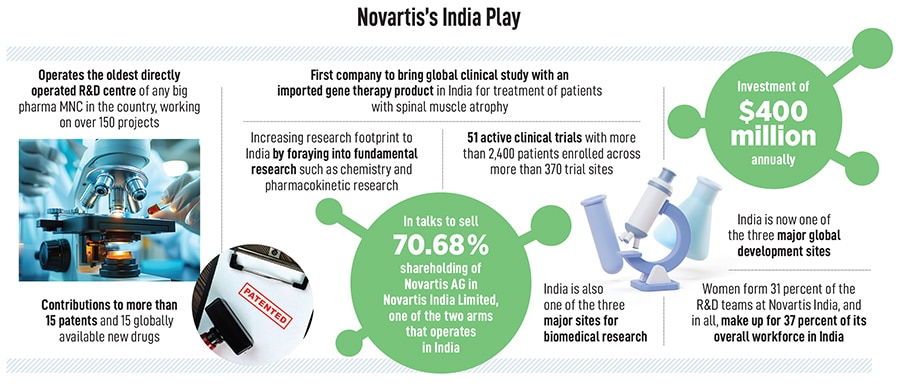

Narasimhan’s visits to India, which have now become an annual affair, highlight Novartis’s ambitions to turn the world’s fastest-growing large economy into its hub for innovation, with everything from artificial intelligence and data science and fundamental research being carried out from its facility in Hyderabad. In all, the company employs as many as 8,300 associates in India and is one of the three major global development sites for Novartis. Hyderabad is also one of the three major sites for biomedical research and of the 8,300 associated, as many as 3,000 are in what the company calls cutting-edge technologies.

“The one area that historically we did not have in India was on the basic science research," Narasimhan says. “I think it’s pretty broadly recognised that India has not been a leader. But we’ve now decided to start doing that as well." In March, Narasimhan announced a plan to bring parts of its research footprint to India, which includes fundamental research such as chemistry and pharmacokinetic (PK) research. PK is the study of how the body interacts with administered substances.

“The talent now is at a level where we think we can do that successfully," Narasimhan says. “Then the question, of course, is at what point could you bring discovery sciences, which is real fundamental research. But it’s a start to even bring PK sciences and chemical sciences into the country. And then, we’ll build from there hopefully over time."

Still, the focus on innovating from India is striking, considering Novartis’s chequered past with the country. In 2013, in a landmark judgment that sent shockwaves across pharmaceutical companies globally, India’s Supreme Court rejected Novartis’s attempt to patent its anticancer drug Gleevec (imatinib mesylate), as it was quite similar to its earlier version. At that time, the company had said that the judgment limits intellectual property protection and discourages future innovation in India.

“We moved from a world where first, it was all about cost arbitrage 15-20 years ago… that’s no longer the case," Narasimhan says about the role India is playing currently. “Then it moved into business process outsourcing and capability centres. Now the hope is, can it (India operations) be a catalyst for transformation?"

“India is a perfect country for talents in basic and applied science with its large population, well-established education system and continuous supply of well-trained scientists in the market," says Mahmud Hassan, director at the Blanche and Irwin Lerner Center for the Study of Pharmaceutical Management Issues at Rutgers Business School. “Narasimhan has made the right decision to look into India for those roles at Novartis."

In many ways, the increased focus on India is also a culmination of the transformation underway at Novartis under Narasimhan, who is attempting to slim down the company to focus entirely on developing innovative medicines. That was also the vision he had set forward while being interviewed for the top job at Novartis. Narasimhan joined Novartis in 2005, after a stint with McKinsey as the global head of disease area strategies at Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

“I worked in vaccines and diagnostics. I worked in generics, and I worked in innovative medicines. I had worked in three of the (at that time) seven divisions," Narasimhan says. “When I came back to Novartis Pharmaceuticals as the head of product development, it struck me that what we were great at is discovering, developing and commercialising novel medicines. So, I had already had it in my mind that focusing on this was going to be our future."

Then, as he became chief medical officer and global head of drug development, a role he held before moving up to the corner room, the global pharmaceutical industry was witnessing the success of new technology platforms such as cell therapy, gene therapy and radioligand therapy. “I began to wonder how could we possibly efficiently allocate capital into those areas and be a leader in all these other domains of health care."

He finally managed to do that, when he took the top job, aged 41 in 2018, and within a month followed it up with the sale of Novartis’s stake in a consumer health care joint venture with GSK for $13 billion.

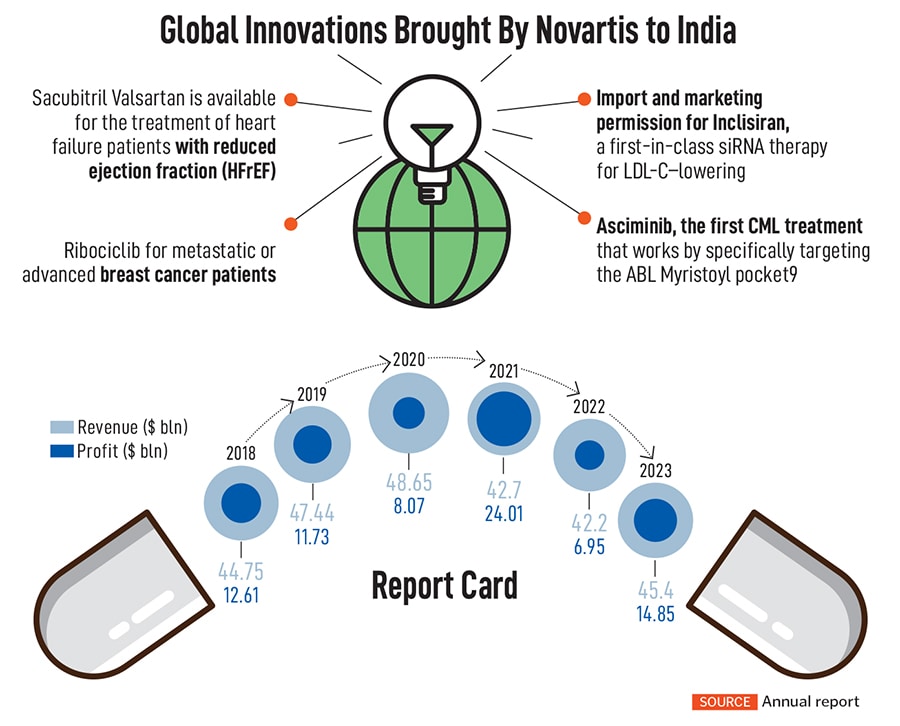

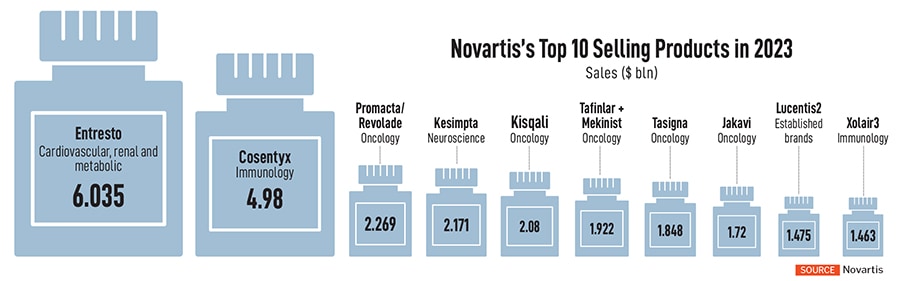

Since then, Novartis has turned its attention to pure-play innovative medicines, with a focus on five therapeutic areas that include cardiovascular, immunology, neuroscience, solid tumors and hematology. Its current portfolio and pipeline include drugs such as Entresto, Kisqali, Iptacopan, Zolgensma, Kesimpta, Leqvio, Cosentyx, Pluvicto, and Scemblix, each of which the company reckons will have multi-billion-dollar peak sales potential. Three other drugs, Remibrutinib, Ianalumab and Pelacarsen, are in the pipeline post 2025. In the process, Novartis also sold off its eye wear business, Alcon, exited its stake in pharma giant Roche for over $20 billion, and spun off its generic medicine arm, Sandoz, in 2023.

“We think about ourselves differentiating around three dynamics," Narasimhan says. “One is in technology platforms. We are the leader in cell and gene therapy. We are the leader in RNA therapeutics and we are the leaders in an oncology area called radioligand therapies. The second is in global reach and the third is in talent where we can access global talent pools."

Today, Novartis operates in some 108 markets, with 40 percent of its revenues coming from the US alone and every year, its medicines reach over 284 million patients. The company also has drug development centres in East Hanover in the US and Switzerland, apart from Hyderabad. In India, the Swiss multinational functions through two different units: Novartis India Limited (NIL), which is listed on the stock exchanges, and Novartis Healthcare Private Limited (NHPL). NIL is currently in the process of being sold while NHPL, which employs over 8,300 people, will begin to play a more significant role in the global operations.

“It’s been an evolving role," Narasimhan says about the Hyderabad operations. “India touches our programmes nearly in every single dimension." Already, the team that designs clinical trials, regulatory filings, biotechnicians and stability testing is all based out of India in addition to corporate functions. The past few years also saw wider integration between research and drug development teams in the US, Switzerland and India. The Hyderabad centre is also home to 20 percent of Novartis’s global leadership roles.

“I think that’s the big shift that’s happened over the last decade," Narasimhan says. “No longer are we putting things here. This centre [Hyderabad] is transforming things across the company."

“For a long time, India had played the role of providing backend and outsourcing support to innovators," says Vishal Manchanda, senior vice president for institutional research at broking firm Systematix Group. “As innovators opt to directly engage in India with their own teams on ground for new chemical entity (NCE) research and development, it would foster a much-needed ecosystem for innovation. India has the required basic talent pool that can be nurtured. Contract research and manufacturing companies have certainly aided in creation of this talent pool."

With its plan to build on PK and chemistry sciences, Novartis will also start hiring more scientists, most likely in hundreds, if not thousands, in the country. “It’s a start and I think we see the talent base," Narasimhan says. “It’s a mix of people who have had experience overseas coming back, but also the research institutes getting better and better."

In addition, Novartis has also been pursuing clinical trials in the country, with 51 active clinical trials involving more than 2,400 patients enrolled across more than 370 trial sites.

Last year, after a few years of sluggish growth, Novartis finally began seeing the results of its pure-play innovation. The cash-rich pharma giant—from all the divestiture—had as many as 10 positive phase three trials. “We had 10 positive phase three readouts last year, one of the highest, we believe, in our history," Narasimhan says.

In the area of cell therapy, the company has brought out a medicine, KYMRIAH, a genetically modified autologous T-cell immunotherapy indicated for the treatment of patients up to 25 years with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that is refractory or in second or later relapse. Other innovations over the past few years include drugs such as Inclisiran, a new anti-cholesterol drug, and Pluvicto, which deals with prostate cancer.

Over the next three years, the company expects its sales growth at five percent annually, led by the likes of drugs such as Kisqali, a breast cancer drug, with a peak annual sales potential of $4 billion. Another drug, Iptacopan, used to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), has become the first oral monotherapy approved by the FDA for a rare blood disorder and has a peak sales potential of $3.6 billion. The company spends over $11 billion a year on its R&D pipeline—almost 25 percent of its sales—making it one of the top five companies in R&D investments.

Still, towards the later part of the decade, Novartis will see some of its marquee products lose patent protection, including the popular heart drug, Entresto. The drug accounts for over $6 billion in sales as of 2023, while another drug, Cosentyx, used for psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, brings nearly $5 billion in sales.

“The reality of the drug industry is you have ups and downs," Narasimhan says. ‘But on average, when we look at the last 20 years, our returns on R&D are well above our cost of capital. The tricky thing is that it’s not a consistent thing. What happens is you’ll have a few hugely successful drugs, and then you’ll have a few years where you don’t have many successes, and you must accept that, and have the patience and wisdom to accept that you will have rough patches." Usually, it takes over seven years to bring a new drug from initial clinical trials to the end of Phase III, with the average cost at $2.3 billion.

That’s also why Novartis has been mopping up biotechnology companies in the last few years, after hiving off its subsidiaries. Last year, Novartis completed 15 deals, of which 13 were valued at less than $1 billion while two others were valued between $1 billion and $5 billion. Among its much-anticipated purchases are German oncology company MorphoSys AG for $2.9 billion, Seattle-based Chinook Therapeutics for more than $3.2 billion to bolster its kidney disease portfolio, and DTx Pharma for $1 billion for its small interfering RNA (siRNA) treatment portfolio for rare diseases.

“We’ve committed to five percent growth between 2023 to 2027," Narasimhan says. “We have 12 launches in the next two years, and we have a pretty full mid-stage pipeline."

More importantly, it’s the gamble on the newer technology that Narasimhan reckons to be the game changer even though traditional areas of medicine in areas of immunology, heart disease and cancer will continue to grow. “If you look at the history of our industry, for the first 80 years, much of the work was with small molecule chemistry," Narasimhan says. Interestingly, his grandfather had worked at the National Chemical Laboratories in Pune in the 1950s and 1960s.

Work on small molecule chemistry led to pills before evolving into injectables, commonly known as biologicals, in the latter half of the last century. “Now we have cell therapy, radioligand, RNA therapeutics and gene editing. And the question is which of these will become the medicines we look back on to say this is the next pillar of our industry," Narasimhan explains. “For me, the most important for Novartis is to make strategic bets in those and we are leading in three of them and making them into significant areas of medicine."

Despite all its focus on innovating from India, the country doesn’t feature in its core markets. Of its global sales of $46 billion last year, Novartis’s sales in the US exceeded $16 billion, with Europe following at $10 billion. China’s market for Novartis is pegged at $4 billion while Japan is at $2 billion. India, for Novartis, accounts for $200 to $300 million in innovative medicines and as part of its pure-play innovative medicines strategy, the company has lined up the US, China, Germany and Japan as its core markets.

“It’s just a factor lower at the moment," Narasimhan says about the Indian market. “The potential is large. China, a few years back, was not a significant market for Novartis. Now it’s our second-largest market and our fastest-growing large market. Because there was a shift to support innovative novel medicines at scale within the country."

The Indian pharma industry has been known as the ‘pharmacy of the world’ for decades. The industry represents over 20 percent of the global generics supply by volume and caters to approximately 60 percent of the global demand for vaccines. “India does not have a biotech ecosystem now," Narasimhan says. “Over the next decade, I would see a biotech ecosystem start to form in India as it has in many places in the US, certain places in Europe and Shanghai. For that to happen, the observation would be that India would also have to form a stronger, and local market for innovative medicines," Narasimhan says.

That may not come easy, especially since the Indian government has a mandate to provide affordable medicines, particularly since the reimbursement mechanism in the country is relatively poor, unlike in the Western economies. That’s also why the Indian government has for long been a staunch supporter of generic medicines, helping bring medicines to the doorsteps of millions of unaffordable groups. “But if you play a long game, if you fast forward a decade or two decades, certainly I think that’s going to be a reality (India becoming a market)," Narasimhan says. “And there will be an opportunity for a company like Novartis."

Much of China’s emergence as a key market for Novartis, offering innovative life-saving drugs and technology has been led by a reform of intellectual property enforcement and data protection, in addition to a reform of the regulatory process and a national system to reimburse novel drugs. “There’s a growing segment of self-pay and self-insured in India, but you would need that to be at a larger scale to create significant markets," Narasimhan adds.

“The pie is becoming larger for more expensive treatment every year," adds Manchanda. “Indian companies are now also driving innovation whether it is Sparc Life run by Sun Pharma or Aurigene life sciences. For a long time, MNCs have been invested in India, but have been primarily selling their branded generics which has now gradually started to meaningfully shift to marketing new chemical entity (NCE) and innovative drugs."

Novartis’s focus on innovating from India is striking. The pharma company employs 8,300 associates in the country

Novartis’s focus on innovating from India is striking. The pharma company employs 8,300 associates in the country

Now with India emerging as a key innovation hub, and Novartis’s restructuring in place, Narasimhan is gearing up for the next phase for the pharmaceutical major.

“I think we’re in a good place," Narasimhan says. “What we need now is to continue the consistent performance for the coming years. But we’ll have ups and downs." It has helped that his training has been in medicine, spending his early years in Africa and India, working across improving access to health care.

“I do think it creates a different lens," Narasimhan says about his training as a doctor. “I focus more on innovation and science. As pure-play, where our lifeblood is discovering and developing and getting these medicines to patients, this is what I’ve spent most of my life working on. So, I think that’s well-aligned."

“Narasimhan took bold actions as soon as he took over the top leadership position of Novartis," says Hassan of Rutgers Business School. “He divested low-performing generic and consumer health businesses, concentrated on the high performing patent-based innovative drugs. I understand he is a popular CEO among his employees with a fascination for high-tech innovation."

So, does he reckon that the work he had set out to do is complete now? “As you get further on in your CEO journey, you have to think about things that will impact medicine far beyond your time, because it takes so long to develop whatever we do… and it will likely be beyond the time I’m CEO," says Narasimhan. “So, it becomes much more about how you can reshape the future of medicine with your work."

At 47, Narasimhan, is only getting started.

First Published: Apr 15, 2024, 11:10

Subscribe Now