Why Indore is attracting entrepreneurs

The 'snack capital of India' is retaining startups of all hues

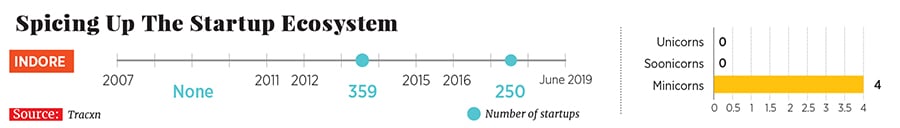

Team ShopKirana: (Seated, from left) Sumit Ghorawat, Deepak Dhanotiya (standing, from left) Tanutejas Saraswat, Akhilesh Gandhi

Team ShopKirana: (Seated, from left) Sumit Ghorawat, Deepak Dhanotiya (standing, from left) Tanutejas Saraswat, Akhilesh Gandhi

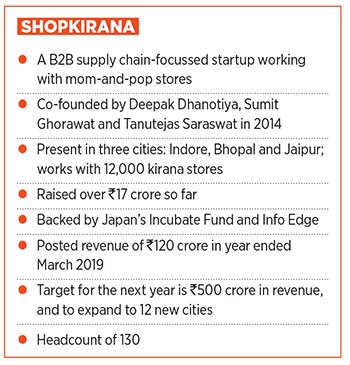

Image: Akashdeep Verma for Forbes India[br]One of the only ways to get out of a tight spot, Sumit Ghorawat reckons quoting Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is to invent your way out. Ghorawat found himself in a sticky situation four years back. After co-founding ShopKirana, a business to business (B2B) supply chain-focussed startup working with mom-and-pop (kirana) stores in December 2014, Ghorawat decided to run a three-month pilot in Mumbai and Indore.

The idea was simple, yet compelling: To find out which of the cities provided a better product-market fit for his fledgling startup. The choice was either to start in a mega city like Mumbai or in a smaller one that presented a big opportunity. At stake was a pie of an estimated 12 million kirana stores across India.

“We were keen to explore both options,” says Ghorawat, as he bites into a slice of cheesy pizza at his headquarters in Indore’s Zanjeerwala Square, one of the busiest intersections in the largest city of Madhya Pradesh. The time taken to reach Zanjeerwala Square from Indore’s Devi Ahilya Bai Holkar International Airport—a stretch of over 11 kilometres—is just 25 minutes during peak hours.

With the mercury hovering around 34 degree Celsius, Ghorawat switches on the air conditioner (AC). The summer here, underlines the alumnus of Carnegie Mellon University, is not as cruel as Delhi’s or as humid as Mumbai’s. “Travel time within the city too doesn’t blow off your fuse,” he smiles, flashing a global report released this year. While Mumbai is the most congested city in the world, Delhi is ranked fourth, according to the Traffic Index report by TomTom, an Amsterdam-headquartered independent location technology specialist. “Welcome to Indore,” he breaks into a hearty laugh, as he grabs another slice of pizza.

Just under the AC in the meeting room, three words—Two Pizza Rule—are boldly inscribed on the wall. Two other co-founders—Deepak Dhanotiya and Tanutejas Saraswat—along with the chief technology officer Akhilesh Gandhi step into the room. “We are here to finish the pizza,” beams Dhanotiya, decoding the Two Pizza Rule propounded by Bezos. During the early days of Amazon, the American entrepreneur believed that every internal team should be so small that it can be fed with two pizzas. “We too started small, with a team of not more than a dozen,” recounts Dhanotiya, as he sheds more light on the Mumbai-Indore pilot of ShopKirana.The result was positive in both the cities. Demand among kiranas was encouraging, the void in the market was conspicuous and an entrepreneur’s desire to solve a ‘pain point’ was satiated. “We were in a fix,” recalls Dhanotiya, who takes care of supply chain operations. What helped the co-founders resolve the dilemma was inspiration from yet another business gem of Bezos: The common question that gets asked in business is, why? That’s a good question, but an equally valid question is why not. “We said why not Indore,” smiles Ghorawat. “And the gambit has worked brilliantly for us.”

Mom-and-Pop Rocks

From just ₹12 crore after the first year of operations, ShopKirana has leapfrogged revenues ten times in four years. The other growth metrics are also promising. It now operates in three cities, including Indore. The target is to add a dozen more by March next year. Headcount has jumped from 26 to 130 over the last five months. “Our growth has increased over eight times during the first five months of this year,” claims Ghorawat. From 1,000 kirana stores that it worked with in the first year, the number swelled to 12,000 by May. “We have just touched the tip of the iceberg,” says Saraswat, who takes care of marketing.

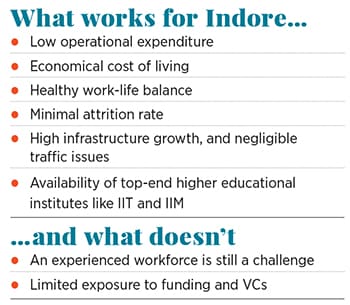

After decades of flaunting the moniker of being the snacks (namkeen) capital of India, Indore is spicing up the startup ecosystem. While 359 startups were founded between 2012 and 2015, over 250 began operations in the past four years (till May 2019), according to Tracxn, a technology data tracker. What’s also comforting is that the city boasts of four ‘minicorns’, or startups that are good candidates for early-stage investments due to their potential to grow in a big market or with great execution in a small market.

A clutch of factors has propelled the city’s startup ecosystem: Low operational expenditure, economical cost of living, better work-life balance, minimal attrition, high infrastructure growth, negligible traffic gridlock, and the availability of top-end higher educational institutes. Indore is the only city that boasts an IIM and IIT. Gandhi explains the tectonic shift. The city grads from the IIM and IIT used to migrate for jobs and venture. “Now there is a reverse brain drain,” he avers.

VCs have taken note. Smaller towns and cities have always been a storehouse of talent, points out K Ganesh, serial entrepreneur and partner at GrowthStory, one of India’s largest entrepreneurship platforms. “It’s only now that we are discovering that,” he says. As India looks to tap deeper into the next 500 million internet user base, the new wave of entrepreneurship will come from people who not just understand that user base but also belong to it. “Startups need to necessarily be based, or have branches, in these small towns to tap into this talent pool,” Ganesh adds. “Since these areas are untapped, the first movers will get good picks.”

One such pick is Gramophone, an agritech startup providing farmers with agronomy services and inputs during the entire cropping cycle. From left: Nishant Vats Mahatre, Tauseef Khan, Harshit Gupta and Ashish Singh

From left: Nishant Vats Mahatre, Tauseef Khan, Harshit Gupta and Ashish Singh

Image: Akashdeep Verma for Forbes India[br]New Crop On The Horizon

Based out of Vijay Nagar, 20 minutes from ShopKirana’s headquarters, Gramophone raised angel money from high-profile investors such as Ravi Garikipati, chief technology officer of Flipkart, and Ajith Pai, director at Green Earth. Co-founded by Nishant Vats Mahatre, Tauseef Khan, Harshit Gupta and Ashish Ranjan Singh in May 2016, the startup recently raised money from Info Edge.

The beginning, though, was not easy for the quartet who had worked in Mumbai and Bengaluru before quitting their jobs and relocating to Indore. While Khan and Mahatre—from IIT-Kharagpur and IIT-Ahmedabad—started the venture in 2016, Gupta from IIT-Madras and Singh from IIM-Ahmedabad joined later as co-founders. A couple of cities such as Kanpur, Jaipur and Delhi-NCR were shortlisted for the agritech startup.

What made Indore pip all the contenders was the agricultural track record of Madhya Pradesh. India’s second largest state by area and fifth largest by population has posted the best agricultural growth in the country over eight years. Khan points out other reasons. Farmers were more receptive to the use of new technologies in Indore, cost of operations was low, and talent was abundant. “Indore made perfect sense,” says Khan.

There was a flip side, though. The agritech segment, as well as the city, fell on the blind spot of VCs. While a couple of them were fascinated with the work done by Gramophone, the very idea of coming to Indore was intimidating. Also missing was a vibrant startup ecosystem in a state that has traditionally been a manufacturing and textile hub.

The situation has changed drastically now. Angel networks have sprung up, co-working places have mushroomed and the entrepreneurial spirit has been boosted by several startup initiatives of the state. The results are visible. “In four years, we will become a unicorn,” grins Khan, adding that the aspiration is not to sweat for the mythical tag. “Impacting the lives of farmers is the main goal.”

Judging a city for its startup potential by the number of unicorns it produces may not be the right way to go about it. A better option may be to gauge the startup fervour, and Indore has plenty of that. Take, for instance, Vaayu India, just 500 metres from Gramophone’s corporate office. Pranav and Priyanka Mokshamar founded Vaayu in late 2015

Pranav and Priyanka Mokshamar founded Vaayu in late 2015

Image: Akashdeep Verma for Forbes India[br]Hybrid is the new cool

A manufacturer of hybrid chillers (AC plus coolers) used for offices, home and large commercial setups, Vaayu was set up by the husband-wife duo of Pranav and Priyanka Mokshamar in 2015. The products are patented and can deliver a temperature of 24-26 degree Celsius with a power consumption saving of almost 85 percent as compared to an AC of a similar tonnage, claims Pranav, who previously worked with Carrier, Samsung and LG for over 14 years.

Situated on the third floor of a building that houses an electronics retail outlet, the office has a photograph of music composer AR Rehman along with the co-founders. Next to it is a framed cheque of ₹36,500 made by Rehman to Vaayu India. “That was the first payment he made for our product installed at one of his studios,” recalls Priyanka. McDonald’s, Volvo Eicher, DRDO and the Kirloskar group are some of its other clients.

Finding a backer for their innovation wasn’t easy. The starting capital—₹60 lakh—came from selling the house. That amount got exhausted soon. Loans from banks and funds from the state’s startup division came to the rescue. Production started in 2016 and the company closed the first year with revenues of ₹27 lakh. In the next two years, it hit a higher growth trajectory, with a top line of ₹1.2 crore and ₹2.3 crore, respectively, and a presence across 24 cities. The revenue target for fiscal 2020: ₹20 crore.

Though Pranav has his roots in Indore, the decision to stick to the city was dictated by the paucity of funds. A Delhi-based industrialist evinced interest to pump in crores if Vaayu relocated to Delhi-NCR. Pranav declined. “Entrepreneurs never take an easy decision,” he says, adding what helped him survive was frugal cost of living.

Back at Zanjeerwala Square, a few Zomato and Swiggy boys are spotted taking orders from a local sandwich brand outlet. Ghorawat, standing at one of the windows, reckons Indore is at the cusp of something special. “Unicorns come here to do business,” he says. “Soon, the city will have its own unicorns,” he smiles, as he opens a pack of Haldiram’s bhuji and heads for a tea break.

First Published: Jul 08, 2019, 14:45

Subscribe Now