In September 2013, private equity (PE) firm TPG Growth invested nearly Rs 150 crore in the medical consumables company, Sutures India, for a 22 percent stake. This was after months of deliberation and discussion, and clearances from the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB). At first glance, it appeared to be another run-of-the-mill deal: Sutures India would use the investment to expand, and TPG would sit quietly with its minority stake, waiting to exit the company on a high. This is a well-traversed route for PE companies globally, and one that they have been following for years.

The TPG-Sutures transaction, however, is far from the ordinary. In the nine months since TPG got a toehold in Sutures, it has put in place a new CEO, mapped a clear path to growth, evaluated more than 15 acquisition targets and is in talks with 3-4 companies for potential buyouts. And, now, the hands-on TPG plans to acquire a majority stake in the company.

Out-of-the-ordinary, though, is increasingly becoming the new normal in the Indian PE industry which has been combating low growth rates in the recent past. The country’s FDI inflow between April 2000 and December 2013 stood at $209.8 billion, according to ‘PE in 2025’, a PwC report released in June of this PEs have invested $80 billion, and nearly 65 percent of these transactions are yet to offer returns. This has forced PE firms to rethink the way they create, tailor, manage and exit deals.

“Lack of returns due to various reasons has put the industry on the edge [where it has] to seek the next big opportunity to make that alpha [returns upward of 25 percent],” says Renuka Ramnath, founder of Multiples Alternate Asset Management. “Modest returns don’t satisfy PE investors if we don’t give back 30 percent, it’s a job not done well.”

The experiences of the recent past have made PEs more cautious in their approach toward new deals. Rigour and diligence on prospective transactions have intensified. For instance, six years ago, a deal would take 6-8 months to be sealed. Today, it takes as long as a year to 18 months. “The search for Shangri-La [perfection] is on. Investors are still trying and testing out various approaches to find the winning formula,” says Bala Deshpande, senior managing director of venture capital (VC) firm New Enterprise Associates (NEA) India. (Deshpande has earlier overseen deals ranging from Rs 6 crore to Rs 300 crore at ICICI Venture.)

And this quest for the “winning formula” has led the Indian PE industry to defy traditional business models that work in other countries.

The Big Hunt

India’s PE industry is just over a decade old, but it has seen a full investment cycle, which includes infusion of capital, gestation (scaling up) and exit. Typically, the investment horizon is of 5-7 years, by the end of which a PE firm needs to give back returns to its Limited Partners or LPs (investors in funds created by VC and PE firms.) Exit routes usually take the form of a public offering, a secondary transaction when another PE firm buys from an existing investor, or when a promoter re-acquires the stake. In emerging markets, LPs usually expect returns that are 3-4 times the capital invested.

This tried-and-tested formula, however, falls through in India. In the first cycle 2004 onward—we are currently in the second cycle—the PE industry failed to offer successful exits and returns despite the fact that the period from 2005 to 2007 was touted as the golden years of private equity in India. Global investors—attracted by the country’s 8 percent GDP growth—thronged the private investment sector. They bet on large-ticket deals assuming India’s growth (coupled with the aspirations of Indian promoters to crack new markets) would automatically generate returns of 15-20 percent. And with a little push from them, returns could go up to 25-30 percent. But investors have been proved wrong.

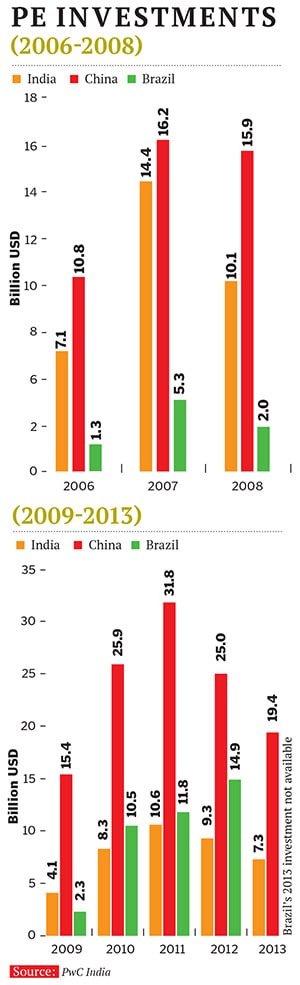

India’s performance when compared to China’s adds insult to injury. PE investment in both countries started at the same time. India’s grew at a moderate pace reaching $2.6 billion by 2005. China’s started slow but, between 2004 and 2005, reached $9.6 billion. The Lehman bankruptcy in 2008 applied temporary brakes on investments in all emerging markets including Brazil. By 2010, however, China and Brazil regained momentum, leaving India behind. No one was prepared for the slowdown that hit the country from 2008.

“In 2003 we were protected the economy had not opened its doors to FDI,” says Vishakha Mulye, managing director and CEO of ICICI Venture. “Today, that’s not the case. In 2014, most of the companies are directly exposed to global markets and the associated volatility, which can be high. I can’t sit on my chair and expect India’s growth to grow my company.”

India’s relative slowdown can be attributed to a number of factors: Significant delays in infrastructure projects, attention-diverting corruption scandals and the slump in domestic demand. The dearth of successful PE exits, exacerbated by the depreciation of the Indian rupee, may have also affected the market. In 2013, when the rupee dropped below 65 to the dollar, PE investors were sitting on losses ranging from 27-33 percent. They were operating in a market with a constricted pipeline of high-quality investment opportunities.

“It’s very difficult to find the right combination of a fast-growing industry, a high-quality asset at the right price and a good promoter. Investors are seeing a lot of deals, but quality is a concern,” says Gaurav Deepak, co-founder and MD, Avendus Capital, one of India’s largest investment banks. “It’s becoming difficult to put capital to work in purely growth-oriented deals.”

Yet, India remains a large and fast-growing market. And PE investors, now much wiser, are becoming more innovative in the way they invest. In the course, they are rewriting the rules of the game.

Rule #1: Be aggressive

One of the first lessons learnt is that passive investments, which give returns in the long term and require minimal involvement, won’t work. This goes against the grain in the traditional way of doing business, PE investors with a minority stake have little or no control over the company, its management and financial decisions. Nearly 70 percent of PE transactions in India are minority deals but, this time around, investors refuse to be reined in. The TPG-Sutures deal is an example of this transformational approach.

Investors argue that the Indian PE space is taking a shape of its own and it would be unfair to follow an investment model created and perfected in the US (a deeper and more mature market). “What kept the industry going earlier is no longer entirely valid,” says Sanjay Nayar, CEO of KKR India.

And for the first time, competitors are collaborating with each other to make huge investments in established companies as well as startups.

In February this year, Goldman Sachs, Mitsui Global Investment and several other PE firms invested Rs 315 crore for a 70 percent stake in the little-known Global Beverages & Foods (a consumer goods company floated by A Mahendran, former managing director of Godrej Consumer Products, a year ago). Even five years ago, this union of forces was unheard of.

Earlier in January, Aditya Birla Nuvo—a unit of the diversified Aditya Birla Group—sold its business process outsourcing unit, Minacs, to a group of investors led by PE firms Capital Square Partners and CX Partners for $260 million. This deal stands out because two PE firms got together to buy and run a company.

Rule #2: Build sector competence

PE firms are shoring up their expertise in specific sectors. Ashish Dhawan, founder and CEO of Central Square Foundation, says most investors want to focus on IT, pharmaceuticals, consumer goods and financial services. The problem is that the number of deployable companies is constricted. “An investor needs to expand its universe of opportunities. Valuations are too high for existing good businesses, and starting from ground zero does make sense sometimes,” says Dhawan (an industry pioneer, he set up ChrysCapital which was one of India’s first PE firms).

Teaming up with international chains even before they enter a new market is one way to “expand the universe of opportunity”.

In November 2013, hamburger chain Burger King Worldwide and PE firm Everstone Capital formed a joint venture (JV) to develop the Burger King brand in India and South East Asia. Under the terms of the partnership, the companies signed a long-term master franchise and development agreement which includes sub-franchise rights for outlets all over the country. Over the next few months, Everstone will work with Burger King’s Asia arm—BK AsiaPac—to set up the supply chain in India and execute a rollout of Burger King outlets.

Everstone is an established player in the food and beverage (F&B) space. In 2008, it invested in Pan India Food Solutions (Blue Foods) which owns Noodle Bar, Bombay Blue and Copper Chimney. Later in 2011, it invested in New Delhi-based restaurant chain Pind Balluchi. Both these companies are a part of Cuisine Asia, a Mauritius-based holding company founded by Everstone Capital Advisors. With the Burger King deal, though, Everstone is experimenting with a JV format.

Asia-focussed PE firm New Silk Route (NSR) has an F&B holding platform, Gastronomy Management Services, and has set aside $100 million for Indian food chains. In 2012, it acquired Bangalore-based Vasudev Adiga’s Fast Food for an undisclosed amount. In 2013, it acquired a stake in the Mumbai-based Moshe’s Fine Foods (a popular chain of restaurants and cafés specialising in Mediterranean cuisine). The eponymous owner, Moshe Shek, now holds a minority stake in the company.

“Based on our learnings from the past, we realise that it makes sense to focus on sectors that one understands well,” says Darius Pandole, partner, New Silk Route Advisors. “The strategy of investing within one’s circle of competence is becoming more important. And, like us, investors are becoming more comfortable taking majority stakes in businesses and infusing the operational capability required to manage these businesses.”

Also, hiring outside experts is always an option, which is what TPG has done. The firm’s exposure to India’s health care sector is limited to companies such as Sutures, but it is looking to acquire hospitals. In April 2014, it hired Vishal Bali, former group chief executive at Fortis Healthcare, to lead its health care deals in India.

“Investors are taking more concentrated bets. They are doing fewer deals but if they are comfortable with a space or a company, they are committing more capital to it. They are realising that unless they bring operational expertise they can’t create value,” says Vish Narain, country head, TPG Growth. “We are very keen on health care delivery. We are also broadening our focus from India to South East Asia including Sri Lanka and Myanmar. We will do large-ticket deals and these could be greenfield developments or acquisitions,” he says.

One of the oldest PE firms in India, ICICI Venture, is also adapting fast to the industry’s changing environment. It is now a partner in BTI Payments, a payments systems company (promoted by The Banktech Group from Australia) which owns, operates and manages ATMs and points-of-sale terminals in the country. “We were very excited about the payments space. When we went around looking for a credible partner, there were very few. And valuations were very high. We decided that this space is big enough and the market can absorb a new entrant,” says ICICI Venture’s Mulye. She believes that backing new businesses with seasoned executives is another big opportunity for the Indian alternate assets industry.![mg_76885_top_pe_deal_280x210.jpg mg_76885_top_pe_deal_280x210.jpg]() Rule #3: Look AT alternate investments

Rule #3: Look AT alternate investments

Innovation is not just restricted to sectors or deals PE firms are fine-tuning their fund themes too. Motilal Oswal Private Equity (MOPE) is one of the firms to focus on investment opportunities in unlisted companies in tier-2 cities. This theme was the biggest differentiator for MOPE’s first fund. With its second fund, which was closed in September last year, it is exploring investment opportunities in the listed space. “While we will continue to focus on tier-2 cities, we know there is a lot of scope in public equity transactions. We are now identifying those opportunities and figuring out if we can delist some companies,” says Vishal Tulsyan, chief executive of MOPE.

Meanwhile, some PE firms are taking a relatively new funding approach. Tata Capital, for instance, raised $600 million for its Tata Opportunities Fund LP in May last year. The fund invests primarily in Tata group companies, but can also invest up to 30 percent of its corpus in non-Tata ventures.

Kedaara Capital Investment Managers—founded by Manish Kejriwal, former head of Temasek India, and Sunish Sharma, former MD of General Atlantic—plans to have two transaction avenues: It will engage in buyouts and takeover carve-outs of Indian conglomerates it will also invest in emerging leaders in sectors such as consumer goods, financial services, technology, agriculture and health care.

Rule #4: Find profit in debt

Last year, when PCR Investments—the holding company of Chennai-based Apollo Hospitals Enterprise—started scouting for capital, it was wooed by a number of investors. The deal (worth Rs 550 crore) was finally sealed by KKR, which has an option of converting its debentures into equity shares at the end of five years. It was KKR’s funding flexibility that swung the deal in its favour.

There’s a consensus that the next big opportunity lies in the debt and structured deals space. Some investors are building flexibility to structure deals that will cater to the requirements of Indian promoters through equity, debt, mezzanine (a hybrid of debt and equity) or convertible securities.

KKR has pioneered this model in India with the help of three entities: A non-banking financial company (NBFC) known as KKR India Financial Services, a debt fund called Alternative Credit Opportunities Fund-I, and KKR India Asset Finance, a real estate NBFC. KKR Financial Services alone has executed more than 35 deals with over 15 distinct groups, and has loaned nearly Rs 9,000 crore since its inception in 2009. A third of the deals that KKR has executed, over the past few years, have already been redeemed. Its latest deal was inked in May: Chennai-based industrial conglomerate Archean Group raised an undisclosed amount in mezzanine funding from the PE firm. The deal allows KKR to convert its investment into ownership if Archean fails to repay the loan in the stipulated time.

![mg_76887_pe_investment_280x210.jpg mg_76887_pe_investment_280x210.jpg]()

KKR’s real estate NBFC has collaborated with the Government of Singapore Investment Corp, the city-state’s sovereign wealth fund. It will lend funds to residential property developers in India, and will have a corpus of $150 million.

“A lot of companies need debt for growth capital. Our strategy here is to be a multi-asset solutions provider led by mezzanine financing which can be very useful for companies still in the growth phase. The added advantage also being that the promoter is not required to dilute stakes or raise expensive equity,” says KKR’s Nayar, adding that private deployment of debt and equity will be a critical source for meeting capital requirements once the economy revives.

KKR works with promoters to understand their requirements, and structures the capital solution based on an iterative process. “We can’t be a single trick pony. The idea is to provide long-term, non-dilutive institutional capital, which is flexible, timely and well-structured,” says BV Krishnan, managing director, KKR Capital Markets.

Other companies, too, are following suit. ICICI Prudential Asset Management Company is looking to raise an alternative debt fund with a corpus of Rs 1,000 crore. CX Partners closed its mezzanine investment fund (CX Intermediate Capital Fund) at $70 million, according to VCCircle.

In May, Aion Capital Partners—a JV between Apollo Global Management and ICICI Venture—closed its special situations fund at $825 million. Aion also manages $120 million of co-invested capital, taking its total assets under management to $945 million. It has already deployed nearly $215 million in Gautam Thapar’s flagship Avantha Holdings and Mumbai-based Jyoti Structures in various debt, equity and other hybrid instruments.

Experts say mezzanine or structured transactions are likely to become more prominent as these can lead to attractive risk-adjusted returns. “When we take a deal, however complex it is, we know there are various atypical pockets of capital available,” says Avendus’s Deepak, adding that the depth of capital available has increased in the last five years.

Rule #5 HAVE A SAFETY NET

With exits getting delayed, a note of discord often sets in among investors and promoters over alleged wilful deceit, non-disclosures and the non-honouring of shareholder agreements. This is where the new concept of insuring PE deals is gaining ground.

Such insurance covers are known as Representations and Warranties (R&W) in legal terms. These ‘reps and warranties’ options ensure a clean exit for the investor. Typically, such covers are bought by the buyer or the seller in a transaction. In the current context, theys are mostly being considered by the buyers (PE firms).

Investors have also started planning about exits at the time of signing the deal, and not as they reach the end of the investment period (which is usually five years in India, this may extend to even 10 years.) If an exit route is not clear, the deal will not happen, says Sanjeev Krishnan, leader, private equity, PwC India, adding that investors no longer trust the current IPO market. “They [investors] don’t want to time the market. They are now starting talks with strategic investors for potential exits through mergers and acquisitions within a year of an investment,” says Krishnan.

A few PE firms are also seeking assured exits in their shareholder agreements with various options in case a pre-determined route does not pan out for unforeseeable reasons. These agreements, however, don’t hold much power for a PE investor who holds a minority stake.

To further safeguard their interests, they are widening the scope of indemnity clauses. For example, in the event of a lawsuit, costs such as legal fees will not affect the PE’s returns. Protection is also being sought for the withholding of taxes and the potential cancelling of licences.

THE ROAD AHEAD

The tough economic cycle of the last few years has been a learning experience for PE firms in terms of funding strategies, transaction structures, investor protection rights and level of operational controls, says Pandole of New Silk Route. The Indian PE industry is now “better equipped to generate returns going ahead”.

More importantly, for all its defiance of traditional business models, India continues to remain an attractive investment destination. Consider the demographic picture: Nearly 50 percent of the country’s 1.2 billion citizens are below the age of 25, and 65 percent are under 35. The SEC B and SEC C population is growing, and if the country manages even a 5 percent growth rate, PEs will reap returns.

Besides urban consumerism, PE fund managers believe that over the next 4-5 years, rural consumption will increase. “Consumer-centric businesses have been big themes for equity investors over the last few years. While this will continue, Indian consumerism is expected to embrace rural markets as well, as growth reaches the interiors of the country,” says PwC India’s Krishnan.

Investors are confident of a revival in the investment cycle, and expect the PE industry to contribute to economic growth on a much larger scale. Over the next decade, deals in both size and nature will start to resemble those in developed nations: They have the potential to reach $40 billion in 2025, says a PwC report, which also estimates that future investment cycles will represent a more mature phase of investing in India.

The PE industry is also expected to consolidate with perhaps no more than 70-80 significant players. There will be a greater degree of segmentation between the different classes of investing, including large buyout funds, late growth investors, early stage investors and venture capital investors. While venture and growth opportunities will continue, experts predict that buyouts will emerge as the biggest investment theme as India Inc deleverages and exits non-core businesses.

PE investors are also eager to support fast-growing Indian companies, with a proven local presence, to expand in the international arena. It’s already happening. “I believe that 2017 is when we will see a clearer picture of Indian VC/PE play, with more clarity on regulations, better corporate governance, and more professionals turning to entrepreneurs, and exits becoming prolific,” says NEA’s Deshpande.

For now, investors remain bullish on India, and will continue to do so. The happy union between the cash-rich PEs and domestic companies, however, comes with a caveat: There has to be economic growth.

Over to the new government.

Rule #3: Look AT alternate investments

Rule #3: Look AT alternate investments