For about a century now, America’s greatest creative export, Hollywood, has been the world’s most successful narrative machine. And one that has won numerous global converts to the American Dream.

So, when US President Donald Trump proposes a sweeping 100 percent tariff on foreign films, without clearly defining what a ‘foreign film’ is, the concept of an ‘American film’ is instantly dragged from the studios onto the chaotic stage of global economics.

The move, a protectionist strategy echoing trade wars on physical goods, exposes how difficult it is to classify a domestic cultural product given the complex, hyper-globalised reality of modern 21st-century filmmaking. Is an American film defined by its financing, production location or the nationality of its crew?

In a post made on Truth Social last week, Trump wrote: “Our movie making business has been stolen from the United States of America, by other countries, just like stealing candy from a baby.”

While it is true that the actual number of films produced in America is dipping, the reasons for the decline are predominantly domestic, not foreign. The pandemic, a content crisis driven by cost inflation, the rise of streaming, and the lingering effects of the screenwriters’ strike are pushing studios to re-evaluate production strategies to avoid further financial risk.

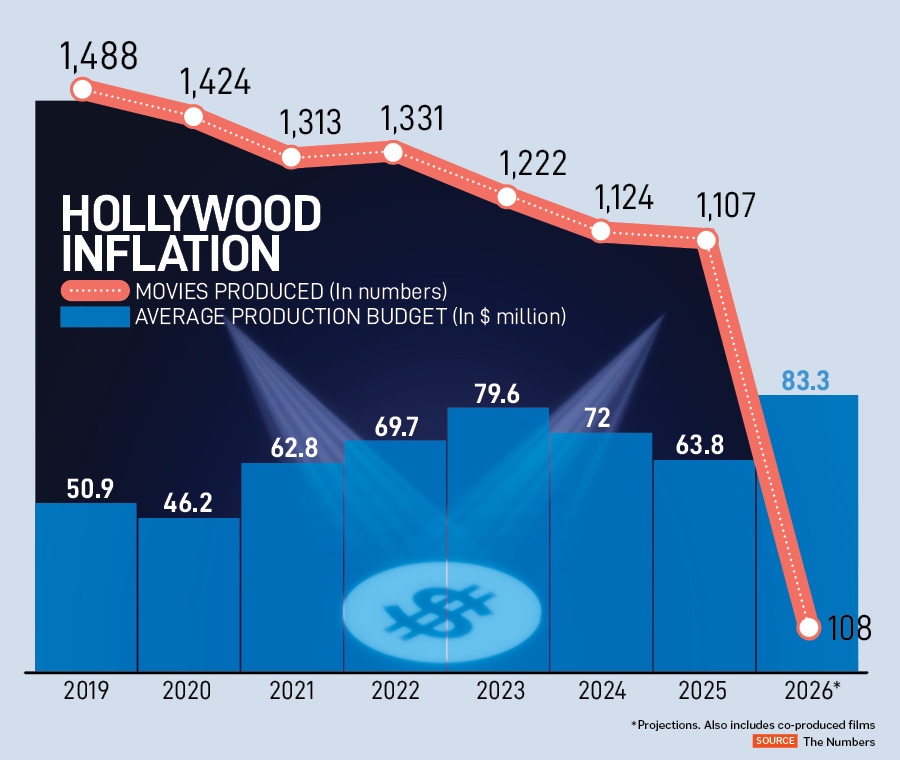

In 2024, America produced just 1,124 films (including co-productions), far below the 2019 high of 1,488. Data shows that the average cost of producing a film, however, has risen by over 40 percent in the same period. While this data may not capture every single film made, it is indicative of the broader trend in the industry.

![]()

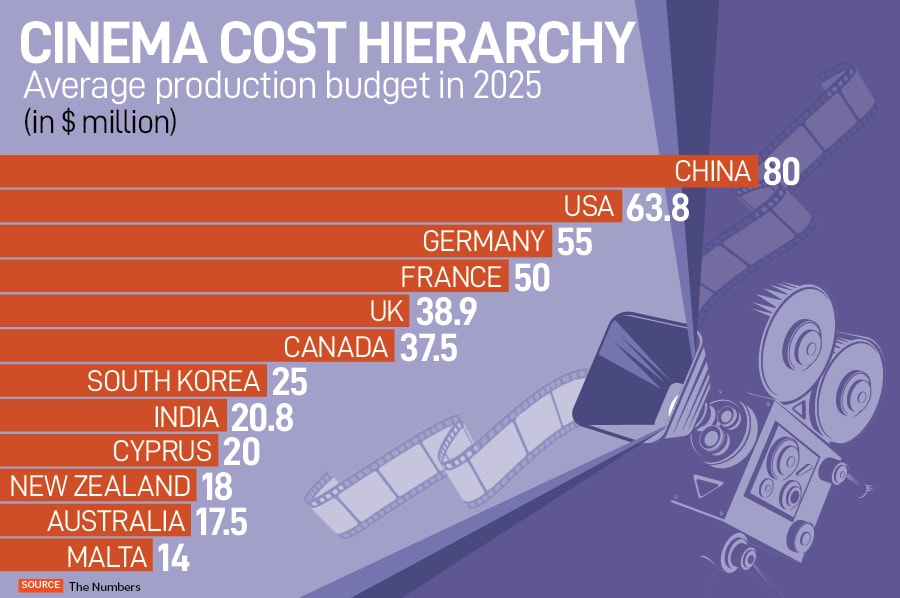

Making films in the US is costly; only China’s 2025 production budget is higher than Hollywood’s. This is perhaps because the contemporary Hollywood blockbuster is not an isolated entity surviving on its own, it is an intricate, multi-national organism.

![]()

Consider a typical big-budget Hollywood blockbuster: The screenplay may be written in Los Angeles, the lead actors might be American, but the director could be from South Korea, the financing could be sourced partly from South Korea and the Czech Republic, the post-production and digital visual effects (VFX) could be done in India, while the actual filming itself may take place in the UK, Austria or the Czech Republic, where generous government tax incentives make the massive budgets viable.

Also read: Trump's film tariffs: Hollywood in shock, uncertainty, and crisis meetings

If a film’s VFX team is primarily based in Mumbai, is it an Indian film? The Lord of the Rings epic, though based on an English author’s book, was a US-New Zealand co-production with a global cast. If a $300 million blockbuster is bankrolled by a foreign equity fund, does it cease to be American?

Trade policy, which traditionally deals with tangible items crossing a border, buckles when faced with the digital delivery of a global entertainment service. Films are no longer transported (or exported) in cans of celluloid; they are digital cinema packages and streaming files, making a tariff an unprecedented tax on digitally delivered services. Imposing a tariff on foreign films could ultimately hurt major US studios and, consequently, American jobs that the policy claims to protect.

Taxing films made outside the US, ironically attacks the very diversity and global talent that feeds Hollywood’s creative edge and keeps it appealing to international audiences.

Suniel Wadhwa, co-founder & director, Karmic Films, who believes that the tariffs are a disruption and a turning point for the Indian film industry, says the real uncertainty lies in how such a levy would even be imposed, whether on licensing, distribution or digital delivery.

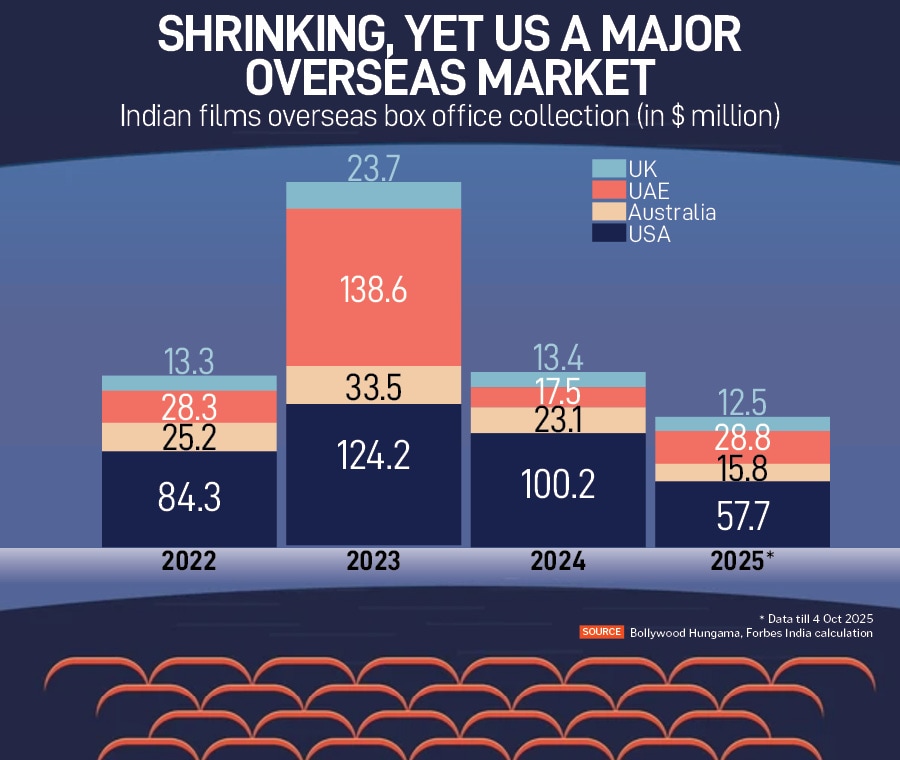

“Post-Covid, the American market has consistently contributed ₹800 to 1,000 crore annually for Hindi, Tamil and Telugu tentpoles—from Pathan, Jawan, Animal, Kalki 2898AD, RRR, Pushpa: The Rule, Jailer, Coolie and others. Smaller and mid-sized titles have little role to play there. A tariff threatens this ₹300 to 500 crore lifeline,” he says.

The US is undoubtedly the most critical overseas market for Indian cinema, easily surpassing the box office collections from other major diaspora centres like Australia, the UK and the UAE for both Bollywood and regional films.

![]()

Shibashish Sarkar, president of Producers Guild of India, says a wait-and-watch strategy till an executive order is passed authorising the tariffs is a prudent approach at this stage of uncertainty.

“Overseas revenue for Indian producers for all languages (taken as a weighted average) is approximately 15 percent. Now US makes up 40 to 45 percent share in the overall overseas market. The revenue size of the US market for Indian films boils down to 6 to 6.5 percent,” he says.

He adds that if Trump levies the tariffs as said, the escalating costs will be equally absorbed by the consumers and the producers. “So even if 100 percent tariff is pushed, the impact on the Indian film industry will be roughly in the range of 3 to 3.5 percent. So, it may not be very significant,” Sarkar explains.

Wadhwa believes that the cost of such a tariff would be ultimately borne by the American consumer.

“Ticket prices could rise from $14 to nearly $20, taking a family outing from $60 to 70 to over $100. Diaspora audiences are price-sensitive; many may skip theatres, wait for OTT premieres, or drift toward piracy. OTT platforms, in turn, may reduce their acquisition of Indian films in the US, making our stories less discoverable,” he says.

In essence, the tariff is a tax on cultural access. It could punish the American public for wanting to see the world’s best films, whether they are a high-grossing Indian action film or an award-winning European drama.