Raid alert: Kabaddi gets a glamorous makeover

How kabaddi in its modern avatar has caught the fancy of the nation

Sandeep Narwal with his father’s ‘No 10’ tractor

Sandeep Narwal with his father’s ‘No 10’ tractor

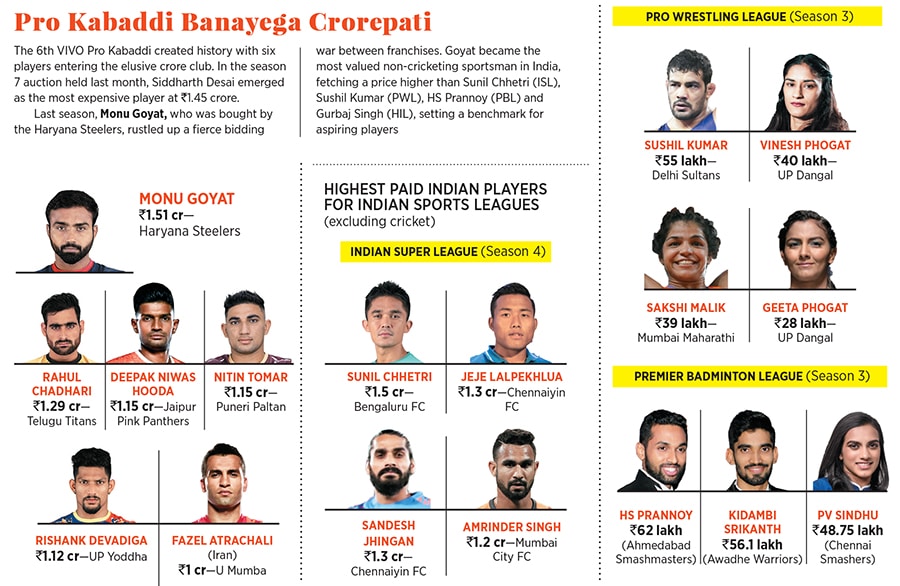

Image: Amit Verma[br] A Skoda Rapid comes to a screeching halt at a 10-acre farm in Kathura village. It’s a bright Saturday morning, the last one in April, and farmers in the Sonipat district of Haryana are getting ready to harvest the standing wheat crop. Sandeep Narwal steps out of his brand new white car. The sky blue tracksuit and white jersey with orange streaks worn by the 5.9 feet Narwal stand out against the backdrop of a dull brown field.Twenty minutes later, around 8.30 am, Narwal’s father reaches the farm in his tractor. In what seems like a tribute to batting maestro Sachin Tendulkar, the blue Ford machine has ‘Number 10’ inscribed in big, bold font. It was in November 2017 when the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) decided to retire Jersey number 10 donned by the batting legend during his 24 year long career.

A Skoda Rapid comes to a screeching halt at a 10-acre farm in Kathura village. It’s a bright Saturday morning, the last one in April, and farmers in the Sonipat district of Haryana are getting ready to harvest the standing wheat crop. Sandeep Narwal steps out of his brand new white car. The sky blue tracksuit and white jersey with orange streaks worn by the 5.9 feet Narwal stand out against the backdrop of a dull brown field.Twenty minutes later, around 8.30 am, Narwal’s father reaches the farm in his tractor. In what seems like a tribute to batting maestro Sachin Tendulkar, the blue Ford machine has ‘Number 10’ inscribed in big, bold font. It was in November 2017 when the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) decided to retire Jersey number 10 donned by the batting legend during his 24 year long career.

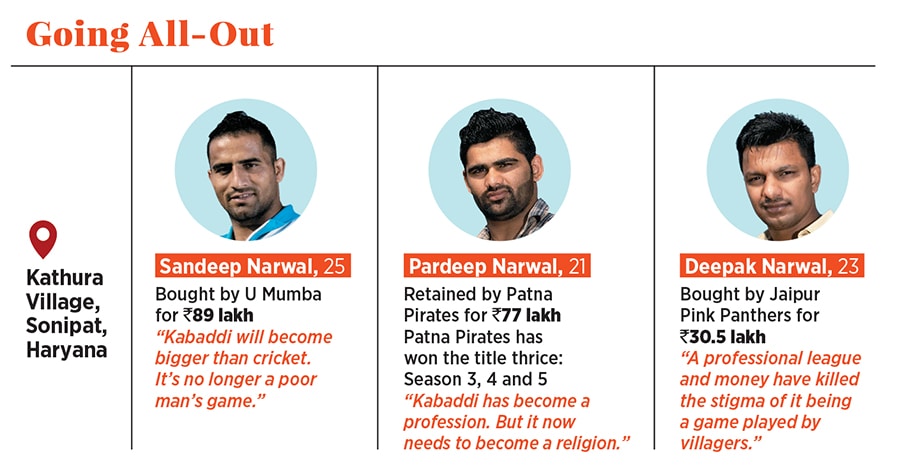

The father-son duo, within a few minutes, get down to work. “I neither played nor watched cricket,” says the senior Narwal, bemused by this writer’s reference to the number 10. “I don’t know what jersey number are you talking about.” Number 10, he explains, is the shirt worn by his son Sandeep. The 25-year-old kabaddi player was bought by the Ronnie Screwvala-owned team U Mumba for a staggering ₹89 lakh in the 2019 auction of the Pro Kabaddi League (PKL) in the second week of April. “Number 10 is kabaddi. Number 10 is not cricket,” he chuckles, beckoning his son who is a few metres away.

Sandeep echoes the sentiments of his father, who once played kabaddi at the state level. “Kabaddi will soon become bigger than cricket,” says Sandeep, who was picked in the first season of PKL for ₹7.4 lakh. “It’s no longer a poor man’s sport,” he adds, as he slaps his thigh with pride. Just two km away from our meeting point is a deserted football ground. Sandeep races to it in his new set of wheels to meet his friends and a few fellow PKL players who have gathered for a training session. Pardeep Narwal, retained by Patna Pirates for ₹77 lakh this season, is nowhere to be seen. “He must be around. His Hyundai Creta SUV is parked here,” grins Sandeep.

Just two km away from our meeting point is a deserted football ground. Sandeep races to it in his new set of wheels to meet his friends and a few fellow PKL players who have gathered for a training session. Pardeep Narwal, retained by Patna Pirates for ₹77 lakh this season, is nowhere to be seen. “He must be around. His Hyundai Creta SUV is parked here,” grins Sandeep. Another Kabaddi buddy Deepak Narwal, bought for ₹30.5 lakh by Jaipur Pink Panthers, makes a style statement in the latest edition of the Mahindra Scorpio. There was a time, Narwal explains, when people used to take up kabaddi to get government jobs. “That era is dead,” says the 23-year-old. “Now kabaddi is a first-choice profession.”

Another Kabaddi buddy Deepak Narwal, bought for ₹30.5 lakh by Jaipur Pink Panthers, makes a style statement in the latest edition of the Mahindra Scorpio. There was a time, Narwal explains, when people used to take up kabaddi to get government jobs. “That era is dead,” says the 23-year-old. “Now kabaddi is a first-choice profession.”

Welcome to an India where a home-grown ancient sport played on mud and largely confined to the rural population has got a glamourous makeover. In its resurrected modern avatar—where the action is beamed live across countries, where top India Inc honchos and Bollywood stars slug it out via their respective teams for the coveted PKL trophy—the desi game is finally winning the hearts and minds of those living in urban India as well. A game that made news fleetingly only when India bagged gold medals at the Asian Games (seven times since its introduction in Beijing in 1990) is now letting its players strike gold with astronomical auction bids. (Ironically, the Indian men didn’t make it to the medals tally at the 2018 Asian Games the women brought home a silver.)

Anand Mahindra, the industrialist who shaped the idea of a professional kabaddi league along with his brother-in-law Charu Sharma, too, didn’t realise that the game would assume such proportions in terms of popularity, viewership, reach and money. “To be very honest, I never thought it would become so big,” he says in an exclusive interview with Forbes India. “I thought it would take time dheere, dheere hoga (it would happen slowly),” he says.

Mahindra explains his take on the rise of kabaddi in India in the book Kabaddi by Nature written by Vivek Chaudhary. The IPL, he tells the author, is the story of the country’s economic growth, a product of a tremendous upsurge in consumer spending, and of a people who have more disposable income, which gives them the money to follow sport. “The PKL story,” he says in the book, “is an emotional one of a country’s that’s more self-assured to the extent that it now embraces something that is truly its own.”

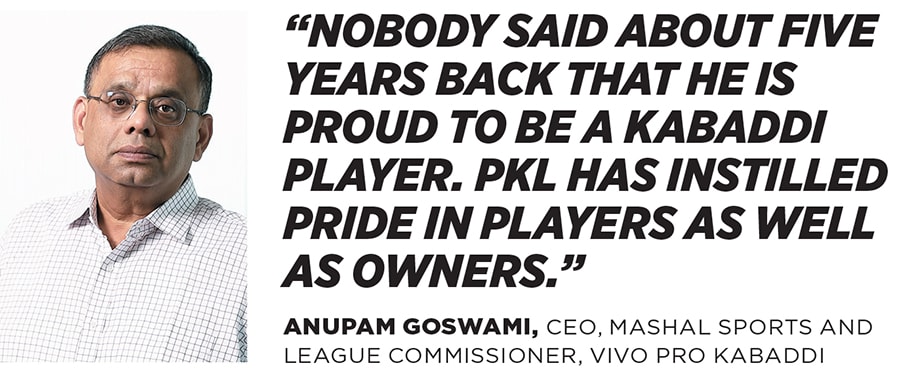

Though Mahindra planted the seed, the next big task was to make kabaddi appear viewer-friendly on television. Anupam Goswami, CEO of Mashal Sports, which runs the PKL and has Star Sports as a majority stakeholder, knew the task wouldn’t be easy. Reason: Sports is about consumption. If Sachin Tendulkar and Shane Warne, he explains, are playing downstairs and nobody is watching, then it’s not sport. It becomes sport only when there are billions consuming it. “That’s what converts the activity into a sport,” says Goswami, who is also the PKL’s league commissioner.There were multiple questions screaming for an answer: How would the field of play look on screen, and inside the stadium? How can a body contact game be shown impressively on TV? “There is nothing called a specialised kabaddi stadium in the country,” he recalls. What perhaps helped all stakeholders the most was that kabaddi was not dead. It was lying unattended in the intensive care unit. “This sport had been sustained in India since the last so many decades it was thriving in small clubs across pockets in Maharashtra and a few other states, and it always made a mark at the Asian Games,” adds Goswami.

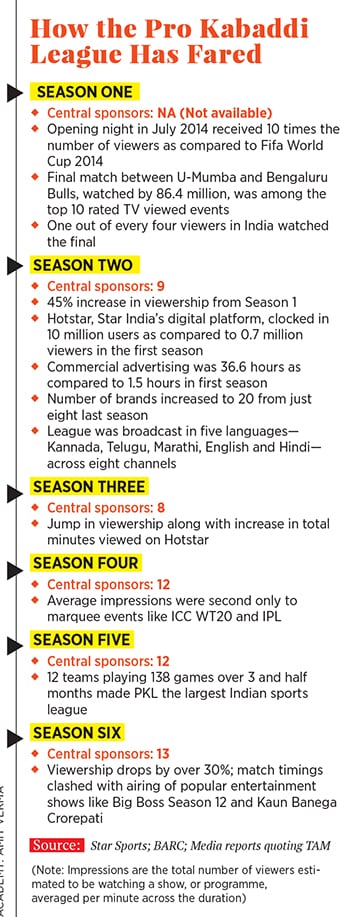

What was now needed the most was interest by corporates, which the league owners managed to generate. The ratings improved, viewership kept increasing—in fact in the fifth season, PKL pipped cricket by garnering more eyeballs than the ongoing India-Sri Lanka Test series—and advertisers started warming up to the idea of looking at the indigenous game.

The turning point came in 2017. After four seasons, Chinese handset maker Vivo came in as the title sponsor by reportedly shelling out ₹300 crore for a five-year deal. By the end of that season, Chaudhary maintains in his book, 313 million viewers had tuned in, registering a cumulative watch time of 100 billion minutes. “PKL had become the second most-followed sports league on TV in the country after the IPL,” he added.

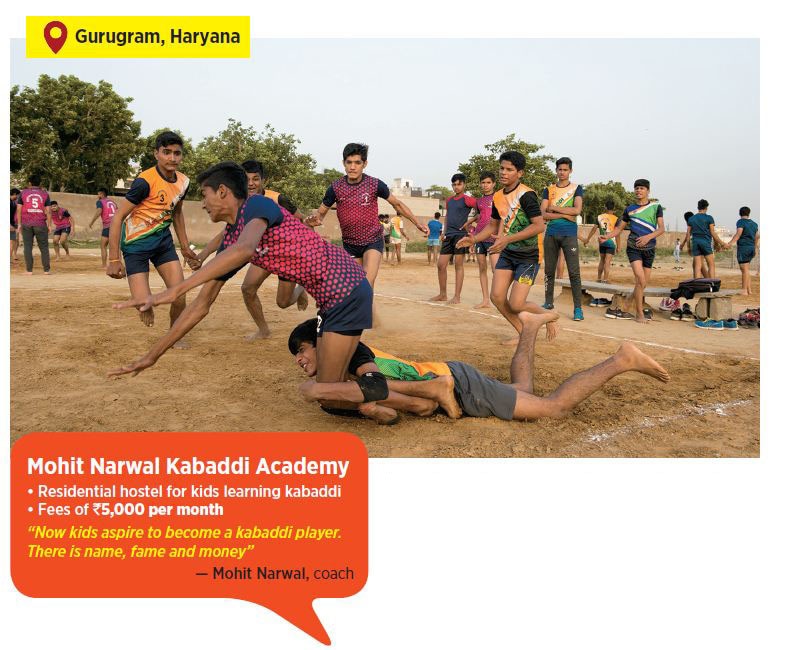

Kabaddi had arrived. Tennis, hockey, badminton, and even football, had been left behind. And there has been no looking back. With more corporates and brands hopping on the bandwagon, the game started getting young followers, many keen to make a career in kabaddi. The move had a cascading effect, as kabaddi coaching centres started sprouting across the country.The Mohit Narwal academy in Gurgaon, Haryana, was one of the earliest ones to spot the trend. Mohit, 23, started a residential hostel for kabaddi kids in 2017. There were not many takers then. He started with a two-room flat and five children. In three years, the academy has transformed into a four-floor building, housing some 70 students between 11 and 23 years. Most of them, Mohit informs, are from Maharashtra and Rajasthan. “The notion of poor kids opting for kabaddi is now outdated,” he says, sharing the economic background of the parents of the kids staying in hostel. While one-third are rich farmers, businessmen and government servants make up the rest.

A promising kabaddi player, Mohit suffered a serious knee injury three years ago. His passion to be part of the game made him start the academy. “I couldn’t achieve my dream. But am happy to help these kids achieve theirs,” he says. Kabbadi, he says, had a rural stigma. “Look at the irony now,” he shrugs. Kabaddi has not only made rural players rich, it has also become glamourous and cool. “Now I get respect as a kabaddi coach. I don’t have to hide my identity,” he says.Meanwhile in Hundalewadi village in Kolhapur district of Maharashtra, the Desai brothers are celebrating two momentous occasions. The first: Both brothers Siddharth and Suraj will play for the same kabaddi team, Telugu Titans. What makes it extra special is the financial reward. At ₹1.45 crore, Siddharth is the costliest player in the PKL’s seventh season. Elder brother Suraj, who was bought for ₹52 lakh in Season 5 by Dabang Delhi but couldn’t play due to injury, was snapped up for ₹10 lakh.

Back in Kathura village, Haryana, as a gruelling day comes to an end for Sandeep, the bulky player get ready for his evening snack. “Ladoos in desi ghee (clarified butter) are what I survive on when the kabaddi season is not on,” he smiles. His younger brother, a farmer, teases him. “Stay fit or else your fan following will get affected.”

Sitting on a plastic chair outside his multi-storied house, Sandeep gazes at the family’s tractor. Number 10, he quips, will stay the Number 1 raider.

First Published: May 29, 2019, 14:37

Subscribe Now