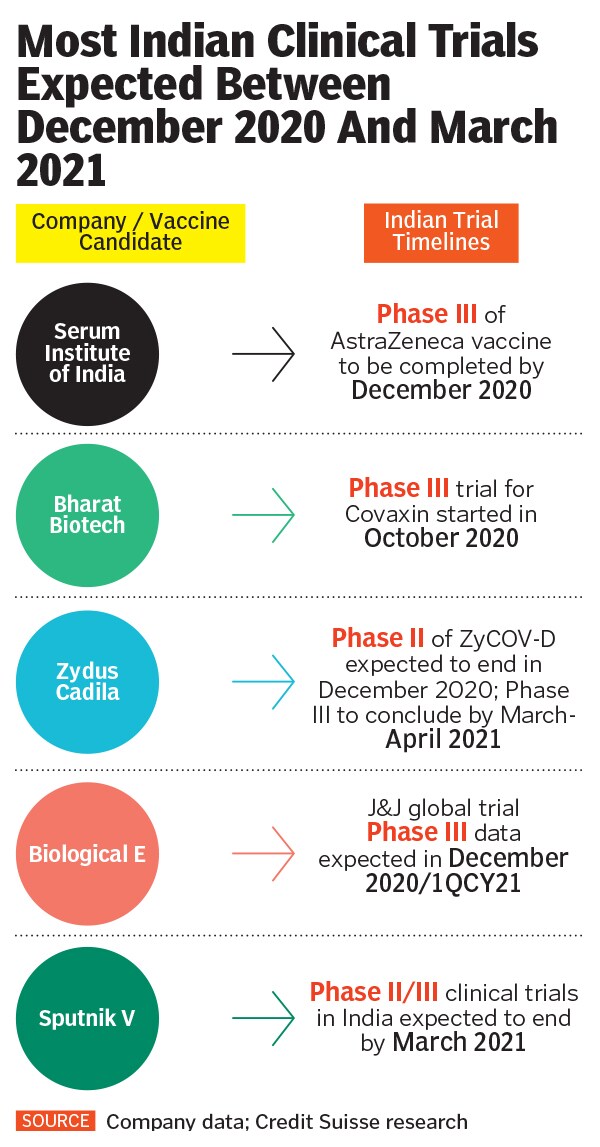

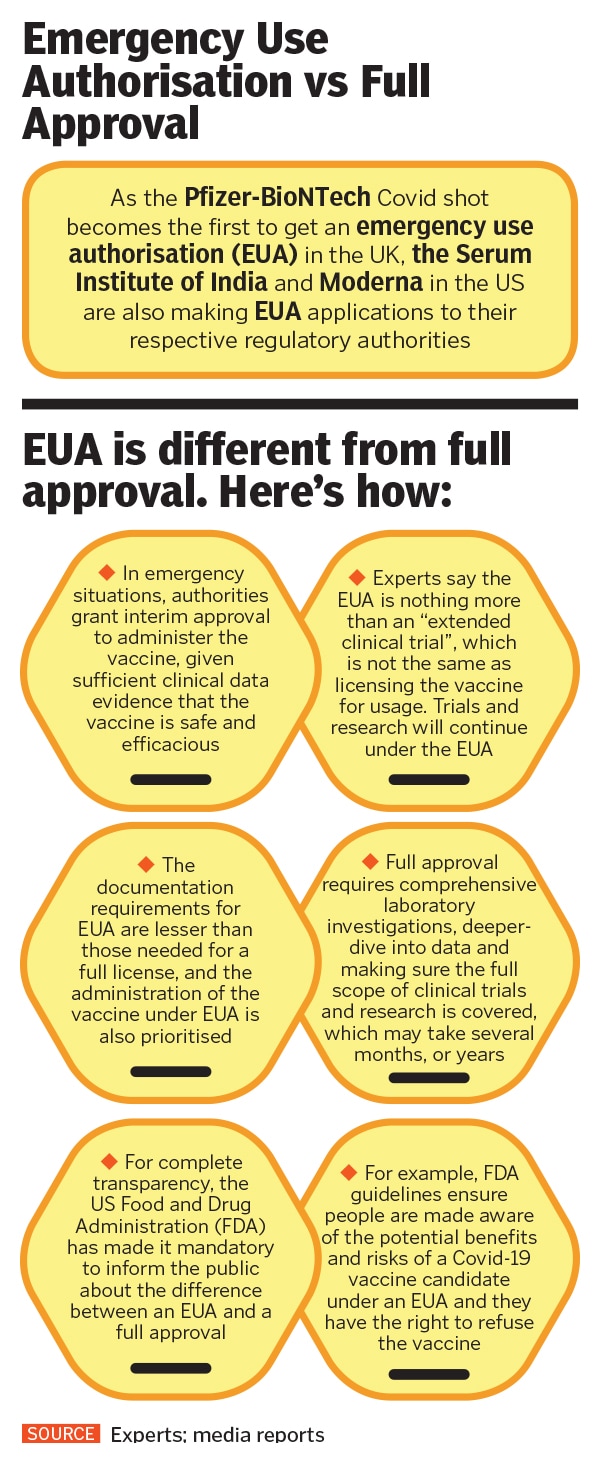

Covid-19 has been pushing the limits of science and regulatory processes. Companies are at the penultimate stage of Phase-III trials around the world, while countries like the UK have already green-lighted emergency-use authorisation (EUA) of the Pfizer Covid vaccine candidate.

On November 17, the US Food and Drug Administration said that reviews of all data and information regarding the EUA granted to Covid-19 drugs and vaccines would be made public. “Today’s transparency action is just one of the number of steps we are taking to ensure public confidence in our EUA review process for drugs and biological products, especially any potential Covid-19 vaccines,” reads a statement by FDA commissioner Stephen Hahn, as published in Reuters.

Around the same time in November, two of India’s largest clinical trials—currently being conducted by Pune-based Serum Institute of India (SII) and Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech respectively—came under scrutiny when one volunteer each from both trials was hospitalised after being administered a vaccination dosage. On Tuesday, even as Union health secretary Rajesh Bhushan assured that vaccine timelines in India will not be affected due to these developments, experts are expecting pharma companies and the regulator Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) to maintain greater transparency and accountability with respect to explaining how exactly evidence is being examined and decisions are being taken with respect to these public health procedures.

“The entire [investigation] process does not have to be put out in the public domain, but more details have to be shared. Right now, we have an unprecedented situation where a trial participant has gone public decrying the clinical trials process,” says Anant Bhan, a bioethics and global health policy researcher. “Confrontational or hyper-aggressive responses by companies and authorities without offering people more clarity will only lead to a trust breakdown in the vaccination process.”

Bhan here is specifically referring to the serious adverse event during the clinical trials of Serum Institue’s Covisheld, where a Chennai-based, 40-year-old volunteer sent a legal notice to SII, demanding a Rs5-crore compensation for a severe neurological reaction he alleged he had developed after being administered a dose of Covihield, the vaccine developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca that the Serum Institute is manufacturing, on October 1.

Serum Institute, the world’s largest vaccine maker by volume that is currently conducting Phase-III trials among 1,600 volunteers in India, dismissed the participant’s allegation as “malicious and misconceived”, and in a statement said that it would seek over Rs100 crore in damages.

Meanwhile, Bharat Biotech had an adverse event during Phase-I of clinical trials of its vaccine candidate Covaxin in August, which was reported in the public domain only in October. The company maintained that the adverse event during Phase-I clinical trials was reported to the regulator within 24 hours of its occurrence and conformation. “The adverse event was investigated thoroughly and was determined as not vaccine related,” the company said in a statement.

Despite hospitalisation of volunteers, the trials in India were not temporarily paused to determine whether the serious adverse events were causally linked to the administration of vaccine doses, while after similar events in the West, UK’s AstraZeneca and US’s Johnson & Johnson had paused their respective clinical trials.

![vaccine infographics_1 vaccine infographics_1]()

“The fact that there is public distrust potential involved, what companies have been doing in Europe and America is sensible. It is reasonable for companies to provide pre-emptive information and explain exactly what happened, how they’ve dealt with the problem, and provide further reassurance that they are following the required protocol,” says immunologist Satyajit Rath.

Although he adds that not pausing clinical trials in India is not a concern if the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) was notified rapidly and it came to the conclusion that the SAE was not trial-related, Rath believes that the cultural framework in India of not having transparency around data will result in those at the receiving end of authority to distrust them. “If instead of threatening to file a lawsuit against the participant, the Serum Institute had just issued a joint statement with the regulatory authority providing more clarity about the adverse event and extending support to the volunteer, there would not have been public concern to this extent in the first place.”

The Adar Poonawalla-led Serum Institute did issue a statement on December 1, assuring that the vaccine won’t be released for mass use unless it is proven “immunogenic and safe”. The company, in its statement, was sympathetic to the volunteer’s medical condition, and assured that regulatory and ethical processes were followed “diligently and strictly” during the trial process. At the time of writing this article, the regulatory authority DCGI had still not issued an official statement regarding this.

Samiran Panda, the chief of epidemiology and communicable diseases at the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), a co-sponsor of the vaccine trial along with the Serum Institute, tells Forbes India that while the regulator is likely to make an official statement soon, “the company [Serum Institute] will only make announcements based on the information that it is receiving from the ethics committee, the DSMB and the regulator”. If raising false hope about a vaccine is bad, Panda added, then “damaging the potential reputation of a vaccine is equally bad”.

“Sometimes, people ask for too much information without recognising the uselessness of it,” says virologist Gangandeep Kang, in an interaction with Forbes India. “You can ask me to make every record identifiable and post it on a public website. That is obviously doable, but how much is it going to cost and how much is it going to delay my group, and its ability to test new interventions? And what value will it add? In the interest of transparency, we can be 100 percent transparent, but that will have very low utility value.”

Clinical trials specialist Santanu Tripathi, who will be the principal investigator of the Covovax vaccine [candidate developed by US company Novavax, for which the ICMR and the Serum Institute have collaborated in India] trial at the School of Tropical Medicine (STM) in Kolkata, agrees with Kang, explaining that a clinical trial is a highly technical process involving many stakeholders, and experts belonging to multiple domains. “While defining transparency, one must understand if the information we put out in the public domain is in the interest of human good, or if it will be redundant, or create undue apprehension.”

At the same time, Tripathi adds that self-regulation is in-built in a clinical trial, and every stakeholder, right from the participants and the company to the investigators, ethics committees and the regulator, must nurture and abide by it. "While in principle and spirit, transparency in clinical trial operations is much desired and welcome, given the criticality of the matter, the nuances demand wider deliberation and general agreement," he said.

Rath believes that it is imperative that the public is made aware of facts, processes and developments that concern them. For instance, he fears that EUA should be treated as “an extended clinical trial, and not as approval of a vaccine candidate”. It is important, he believes, for regulators and stakeholders to make people aware of the distinction. At the time of writing the story, AIIMS director Randeep Guleria had told news agency ANI that Indian regulatory authorities are likely to provide EUA to a vaccine candidate by the end of December. “Safety and efficacy of vaccines are not compromised at all,” he said, explaining that short-term clinical data indicated that vaccines are safe for EUA.

![vaccine infographics_2 vaccine infographics_2]()

Kang adds that if the Serum Institute provides at least two months of safety and immunogenicity data to the regulator, along with safety and efficacy data from the AstraZeneca trials globally, and if they are found to be equivalent, then there is “no reason why we can’t take the efficacy data from the UK, accept that and give the vaccine an emergency use authorisation in India”.

Read related story: We can be 100% transparent with Covid-19 trials, but that will have very low utility value: Dr Gagandeep Kang