Rare earths possess magnetic and phosphorescent properties important to innovations from electric cars to artificial intelligence, making the minerals an increasingly contentious issue in international relations. For example, the United States has long sought an agreement with Ukraine to obtain access to its deposits, discussions that took on greater urgency following Russia’s 2022 invasion.

Using patent records, the team found a positive downstream effect from this thorny issue in international trade. The study provides a potent reminder that markets are always changing, sometimes in surprising ways.

Also Read: The rare earth magnet shortage: What can Indian automakers do?

What exactly are rare earths

Rare earth elements are a group of 17 metals with unique magnetic, catalytic, and luminescent properties, such as scandium, yttrium, and gadolinium. Their unpaired electrons enable them to store magnetic energy, and they can act as catalysts for phosphors in lights and computer screens.

Unlocking their potential has created new capabilities in electronics, aerospace, clean energy, medical equipment, and a range of other industries. They’re critical to electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines, medical imaging machinery, and semiconductors.

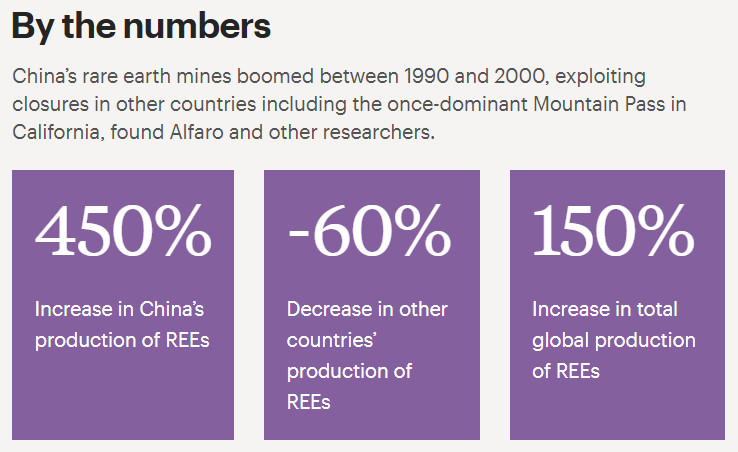

China has been the dominant player in rare earth materials for almost 50 years, producing 73,000 metric tons between 1990 and 2000. China’s market share in global mine production of rare earths reached 98% in 2009, according to the study.

![]()

But since 2010, when a dispute with Japan led China to tighten exports, China has sought to tighten control of the market, citing illegal mining and environmental protection. In October, the US government threatened to retaliate with more tariffs after China added five new rare earth elements to its list of export controls.

Trade war cause and effect

To understand how the rare earths market functions, Alfaro and her team analyzed the effects of China’s 2010 restrictions, mining data from 30,000 patents worldwide.

They built a novel database that categorizes the use of rare earths by industry. They collected information on productivity and built a simulation model to challenge their assumptions.

The researchers found a “surge of patenting activity” from China’s competitors as firms looked for substitute materials and to develop methods for using rare earths more effectively in production.

Industries outside China with the greatest dependence on rare earths produced a 7.4% larger stock of related patents after the controls. Rare earth-related patents outpaced overall industry patents, the study indicated.

In addition to substitute materials, the study authors also examined patents on processes designed to reduce the use of rare earths in their products or eliminate them altogether.

For example, Toyota filed a patent in 2016 designed to eliminate or reduce the use of dysprosium and neodymium in electric motor magnets. The company cited supply issues as a factor in its patent applications. Other auto manufacturers have taken similar steps.

Controls lead to productivity gains

An additional phase of the study examined the impact of the new market restrictions on productivity.

Non-Chinese firms with the heaviest use of rare earths grew both total productivity and labor productivity, the researchers found. In contrast, Chinese domestic industries that used rare earths most heavily saw productivity declines.

The controls had a similar effect on global trade. Researchers tracked trade flows and found that rare earth–intensive industries outside China increased their exports by about 0.3 percentage points per year more than less-exposed industries. In effect, firms that were initially squeezed by the supply shock became more competitive in global markets.

“Our key finding is that policies that create an adverse supply shock of essential inputs can trigger innovation, long-term productivity growth, and reallocation of economic activity towards downstream sectors that are intensively using these essential inputs,” the researchers conclude.

This article was provided with permission from

Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.