Taiwanese whiskey Kavalan is fetching Scottish prices

Whiskey is a premium call for Albert Lee as he guides Taiwan family's food and beverage group

Nice work if you can get it: “I’m just a wage earner who toils for my father,” says Albert Lee

Image: Craig Ferguson for Forbes

Barriers to producing a renowned whiskey in Taiwan were numerous. For one, when the Lee beverage clan sought to touch alcohol, even to brew beer, they were rebuffed by the government in 1995. It didn’t want to part with a state monopoly.

Patriarch Lee Tien-Tsai persevered through legal changes, ultimately shifting his aim to a single-malt spirit. By then, it was 2005, and the product was named Kavalan, in honour of the pioneering tribe of the springwater-rich Yilan area, a 40-minute drive from Taipei.

Unlike Scottish single malts that carry similar price tags, Kavalan would not require 12 or more years of ageing in the barrel. The warm and humid conditions in Taiwan speed up that process to half or less the time. That’s an inventory advantage many quality liquor producers would envy. But, in that environment, a thirstier “Angel’s share”—the amount of whiskey lost due to evaporation, several times as much as in a cooler, drier place—negates much of that edge and prompts bottle tabs beginning near $100 at retail.

But Kavalan gets that price, thanks to a string of international prizes and growing consumer recognition. (A recent score: Chuck Rhoades, the lead prosecutor portrayed by American actor Paul Giamatti on the Showtime series Billions, avers that “The Taiwanese do it better than the Scots these days”, after sipping a $200-plus Kavalan Solist Vinho Barrique.) Its undisclosed global volume is still thought to be a small fraction of the traditional single-malt names (Macallan, Glenfiddich and Glenlivet), and 60 percent of sales occur at home, but the name is being splashed from glossy magazine ads to Times Square billboards.

It may be, however, that the real secret to Kavalan’s early success is not so much the water or the air or even an in-house Scottish consultant but the founder’s perfectionist son. Albert Lee Yu-Ting, turning 52, has made the whiskey his personal obsession since he was promoted to vice president of the family group in 2003.

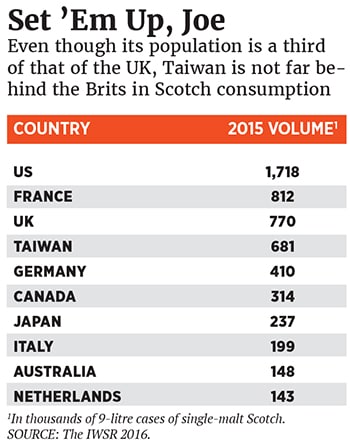

Taiwan had joined the WTO trade pact the year before, opening up export possibilities. That’s vital to high-end whiskey-making, although the home island is no piker when it comes to per capita consumption of the stuff (see table).

King Car (the name roughly translates from Chinese words meaning “to drive wealth”) knew its way around other beverages. The patriarch started it in 1979 to sell root beer. That didn’t work, but, by 1982, he acted on a Japanese mentor’s advice to create Mr Brown, a canned coffee brand. (That’s the first foreign surname locals pick up in their mandatory English classes.) A decade later, he owned the Taiwan market and was exporting. In 1998 came Mr Brown cafes, now totalling 50 on the island. They tend to be in secondary business districts where Starbucks doesn’t locate, but the properties were acquired opportunistically and have appreciated greatly in value.As an overall food conglomerate, unlisted King Car (exceeding $500 million in claimed latest-year revenues) is big enough to put Lee Tian-Tsai on Taiwan’s 50 Richest list at nearly a billion-dollar net worth. Albert, as CEO since 2013, after his dad suffered a minor stroke, has plenty to occupy his time (younger brother Yu-Cheng has charge of the group’s horticulture/aquaculture arms), but Kavalan remains his special interest. “Five gold medals in six years—that’s an unmatched track record in the world,” he says from the group’s European-style whiskey castle, which has attracted a million visitors a year.

Then he catches himself as he turns to his staff, discouraging them from complacency. “Let’s continue to lie low and keep an eye on what others are up to. Then catch up, or we will be left behind,” he adds.

With their chosen barrels and yeast formulas, Kavalan spirits, aged four to six years, taste as smooth and mellow as their sophisticated peers, with a fruitier character. Demand is out there. The immediate challenge has been capacity for volume growth. “In the next decade or two, we will spare no effort to rack up sales,” Albert vows. A year ago, dad gave his go-ahead “within minutes” for a $30 million copper-pot-still expansion, which will see annual production double to 10 million bottles this year to begin filling global connoisseur demand over the next decade or so. That expanded capacity should translate into a retail value of $1 billion, with the wholesale share assuming a more meaningful part of King Car’s revenues.

At home, Kavalan is still overcoming hurdles to woo single-malt amateurs, who wine and dine guests with aged imported whiskies “for fear of losing face”, says a rival brand’s sales agent in Taipei. Kavalan has its own domestic retail outlets, since the label is too pricey for many of Taiwan’s liquor stores. Albert plans to double their number to 100 in the next three years.

The International Wine & Spirits Record forecasts that, globally, whiskey will overtake vodka to become the world’s second-largest spirits category by 2019. IWSR analyst Tommy Keeling says Kavalan’s trajectory could have it replicating the success of the Japanese whisky Suntory, which was driven by quality, international accolades and media visibility, particularly in the film Lost In Translation. Kavalan can “rely on the exoticism, the novelty of being a Taiwanese brand and a rarity, and try to appeal to consumers in some other ways, not just price”, says Keeling.

A liquor notable for patient distilling fits with Lee Tien-Tsai’s business character over the decades. “He is more into the hard-earned money—one or two bucks at a time for a long, long time,” Albert observes.

King Car’s strong cash flows have provided a sufficient capital cushion to see Kavalan through a prolonged payback period, says Allen Tsai, founder and executive director of Taiwan Institute of Directors, which studies the succession of family businesses. “King Car is the legacy dad passes on, but Kavalan will be the brainchild of Albert,” Tsai says.

The No 1 son exhibits a modest streak (“I’m just a wage earner who toils for my father”) but showed decisive leadership early on. In 2008, Tsai recalls, King Car was among Taiwan producers facing a melamine milk crisis (in its instant coffee blends, for example), and the son quickly executed recalls at a minimum loss of $1.5 million.

Albert honours the entrepreneurial ethos of his father’s generation and is said to have faithfully avoided scion-slacking. Says one of his close friends, Khieng Puong, husband to the youngest daughter of late Formosa Plastics founder Wang Yung-ching: “Like his father, he’s a workaholic, who always shares rides with dad to work at an early hour no matter how late he schmoozed the previous night.”

Sounds like the right recipe for a budding whiskey baron.

First Published: Feb 24, 2017, 06:16

Subscribe Now