The billionaire who single-handedly changed how America shops has an inner sanctum as enigmatic as he is: The corner of a nondescript office building in Columbus, Ohio, across the road from a garbage dump, behind a security gate festooned with “Do Not Enter” signs. While the communal spaces are properly blinged-out with pink walls, lacy bits of lingerie and a big screen rolling endless tape of nearly-naked supermodels, the chamber itself is a confused mess of binders and papers straight out of The Absent-Minded Professor. Nearly every surface is devoted to knick-knacks—a three-foot-long pencil here, an Ohio State Monopoly board there—or stacks of books.

The irony seems lost on Leslie “Les” Wexner, who built Victoria’s Secret, Pink, Express and The Limited into one of America’s all-time great retail fortunes. “When I was a kid, before my first store, they talked about stores as theatre and retail as theatre. It still is,” says the 77-year-old. “Retailing is a free form of entertainment.”

Yet, this impresario shuns the spotlight. He’s the CEO of a large publicly traded company, yet he rarely speaks on earnings calls. One of the legends of his industry, yet he almost never speaks to the press. Wexner is so elusive that most assume the brains of Victoria’s Secret is surely some female visionary in the mould of a Sara Blakely or Tory Burch, or else a Hugh Hefner Lothario type.

In reality, Wexner—net worth $6.2 billion, good enough to make it to No 80 on The Forbes 400—is an in- trospective guy who has been ques- tioning his every move for decades. His professional success results from a compulsive restlessness and dissatisfaction that steer him away from the herd. His first great insight was focusing on a few products (The Limited) at the apex of the department store age. He expanded nationally when the biggest retail stores were regional concerns. When most competitors rushed overseas, he held back. And in his biggest score of all, he reimagined the lingerie business as a wholesome enterprise that could thrive next to the food court and the multiplex, rather than the boudoir and the peep show.

Being a chronic contrarian is not easy. About to open his first store at the age of 26, Wexner woke up screaming every night. In his 30s, he was a distraught millionaire, searching for a purpose greater than adding more zeroes to his net worth. The money came easier than the fulfilment, and by his 50s, he was running more than a dozen businesses, five of them doing sales of $1 billion or more. Then, char- acteristically, he decided he had it all wrong and from 1998 to 2007, spun off or sold The Limited, Limited Too, Abercrombie & Fitch, Express, Lane Bryant and Lerner New York. He kept Victoria’s Secret, betting that the brand’s emotional resonance would support higher margins in an increas- ingly commoditised apparel space.

“What I worry about is a fear that you won’t have the idea or that you have figured it out wrong,” he says.

Wexner now owns the only three bra labels that matter: Victoria’s Secret, Pink and La Senza. Together they make up 41 percent of America’s $13.2 billion lingerie market. Their next closest competitor has a one percent market share. Bath & Body Works, the world’s largest beauty retailer, is his too. He holds all of them under his thriving parent company, L Brands.

L Brands’s 2,949 wholly owned stores sell over $11 billion worth of bras, panties, soaps and other such products a year.

Same-store sales have increased in each of the last 19 quarters. Brilliant marketing, especially the annual Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show, accounts for some of this success. But in the disembodied era of ecommerce, hands-on customer service matters, too. Shoppers can buy quality T-shirts and pants from a multitude of different retailers, but bras are different. Eighty percent of women in America wear the wrong-size bra. Computers can’t measure them for a proper fit, and employees at, say, Target won’t. But Victoria’s Secret workers do, and women pay the company back with loyalty. Ninety-nine percent of L Brands stores turned a profit in 2013, and Victoria’s Secret’s operating margins are 17 percent, triple the industry average. In defiance of ecommerce evangelists, he opened 50 new locations last year. His online business is not the focus, but it’s doing just fine, accounting for $1.5 billion of his annual sales.

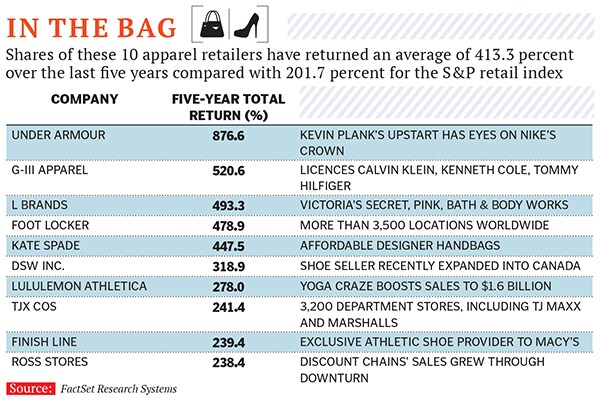

Those numbers have translated into huge gains on the stock market, where L Brands shares shot up by 11 percent last year, twice as much as the S&P retail index. Over the last five years, L Brands shares have returned nearly 500 percent, more than almost any other retailer in North America (the two exceptions: Under Armour and G-III Apparel). “They’ve done such an unbelievable job dominating the market,” says Wells Fargo retail analyst Paul Lejuez. “I can’t think of anyone who has been more successful.”

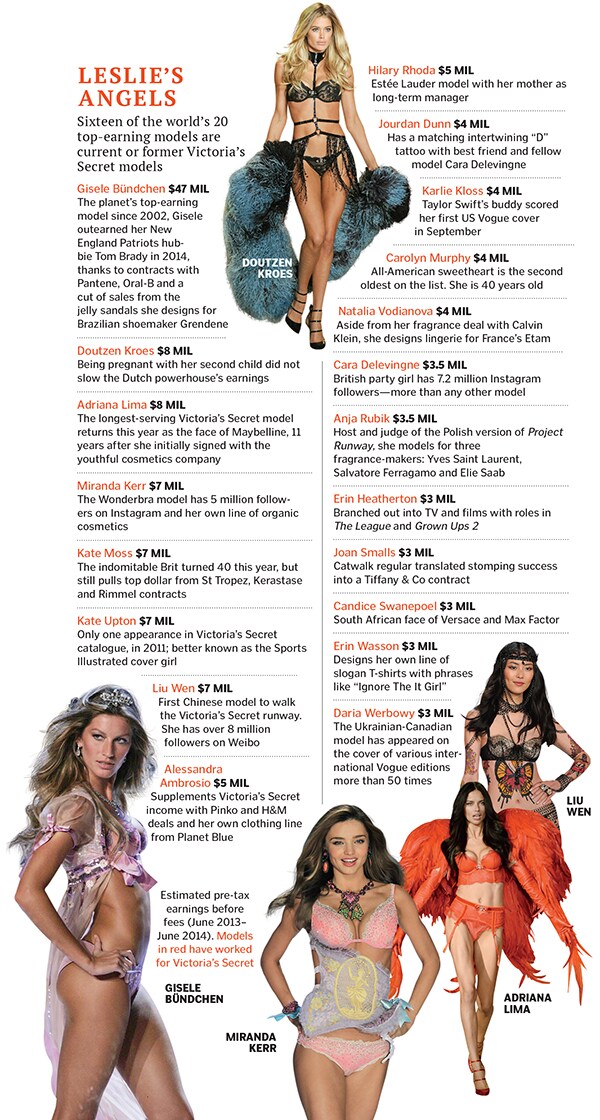

Victoria’s Secret is already famous around the world, not because of its stores, but because of its scantily-clad models, who hail from every continent except Antarctica. Viewers tune in from 192 countries around the world to watch the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show on TV each year.

Yet, Wexner has barely begun expanding Victoria’s Secret stores worldwide. “Our priority is our domestic business, but we could see that our international business could be as big or even bigger,” Wexner says. In 2012, Victoria’s Secret expanded its wholly owned stores beyond North America, opening two locations in London. Five more stores have since popped up in the UK, and together they’re already grossing over $100 million.

Wexner is also taking the brand into Asia and the Middle East through a new franchise model, with virtually no risk for L Brands. Wexner has more than 600 fran- chised stores around the world. L Brands invests no capital in the stores and is virtually guaranteed a profit from day one, charging an outsized royalty of between 10 percent and 15 percent. The opportunity is so big that, for the first time ever, Wexner is moving the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show outside the US, taking it to London this December. “They’re only scratching the surface of international expansion,” says Matthew McClintock, retail analyst at Barclays, who envisions a $10 billion business overseas within a decade. “It’s a gold mine.”

Wexner’s reflexive questioning drew him into retail in the first place. After getting his undergrad degree at Ohio State in 1959, he dropped out of its law school and returned home to help around the small family store, Leslie’s, named after him. When his father left on vacation, Wexner tried to solve the riddle of why his dad had always worked so hard, but never made any money. He found a stack of invoices, and on a piece of scrap paper, began tallying the cost and profit from each item in the store.

The numbers added up to a counter-intuitive conclusion. Although big-ticket items like dresses and coats looked like they had huge margins, they actually made no money because they sat on racks forever. All of the store’s profit came from less glamorous items like shirts and pants. Wexner’s parents returned home to find that their son thought he could run their store better than they could. Wexner told his dad to take out the coats and replace them with more blouses and pants. His dad told him to get a job.

He did, founding a rival store to his father’s with a $5,000 loan from his aunt in 1963. He put a limited selection of clothing in the store—only the shirts and pants on a few shelves— and named the place The Limited. Wexner signed a lease for a second store before even opening his first, convinced that if the idea worked in one store, it would work in another.

Before selling a single shirt, he owed his landlords $1 million. He had nightmares every night and eventually started getting belly pains. The doctor told him he was too young to have a stomach ulcer, but the X-ray clearly showed the hole that fear had eaten through his stomach.

![mg_78235_victoria_secret_model_280x210.jpg mg_78235_victoria_secret_model_280x210.jpg]()

He made $20,000 of profit in his first year, twice as much as his dad’s best. The secret was his focus on only a few products, a revolutionary idea at the time. Wexner says that Steve Jobs (or presumably it was Jobs—“what’s-his-name from Apple,” Wexner says off-handedly) was one of the many to credit The Limited boss with inventing specialty retail. “Probably did,” he shrugs.

Curious about how far his idea could take him, Wexner bought a US map and a compass. He drew a circle to see everywhere he could get from Columbus in a day. Commercial airlines had just started using jets in the 1950s, significantly extending the radius of Wexner’s compass and bringing 70 percent of the US population within two hours of the headquarters. Leveraging his centralised location and jet travel, Wexner decided he could build a national chain. By 1973, Wexner was well on his way, with 41 stores selling $26 million worth of pants, skirts and blouses.

Having proven that narrowly focussed stores appealed to female customers, he set about creating new companies, built in The Limited’s mould. He launched Express in 1980, targeting younger women with more colourful, casual clothes. And he got curious about a small chain of lingerie shops he had seen in San Francisco called Victoria’s Secret. He never could find out much about them because their owner, Roy Raymond, clammed up everytime Wexner asked questions. But in 1982, Raymond called up Wexner, saying he wanted to talk. Raymond was on the verge of bankruptcy and was hoping Wexner would buy his six stores before the sheriff took them. “I literally flew out that afternoon and met him in the evening and bought the business,” says Wexner. “I didn’t know anything about it.”

His financial advisors had warned him that $1 million was too much for the business. Wexner let Raymond run it under The Limit- ed’s umbrella for a while, and his deputies rolled their eyes as it bled millions more. When they examined the financials more closely, they re- alised the only way Raymond had been making any money before the acquisition was from a secondary business, selling mail-order sex toys. Wexner freed Raymond and moved the headquarters to Columbus. (Raymond’s next business went bankrupt in 1986, he got divorced in 1993, and jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge later that year.)

Wexner began restructuring Victoria’s Secret. “I had never seen a lingerie specialty store,” Wexner says. “But then, when you look at it from a business point of view, it wasn’t really a business.” Wexner threw The Limited’s operational know-how behind the business and cleaned up its broken-down finances. “Roy just didn’t get that piece,” admits his former wife, Gaye Raymond. “There weren’t a lot of stringent limits and boundaries on spending or planning.”

In typical fashion, Wexner didn’t dream up the idea for America’s first lingerie chain he just followed his curiosity, played with the concept for a few years, and ended up thinking about it in a new way. The same sort of experimentation was behind the launch of a low-key lingerie fashion show in 1995. “The idea just came from trial and error,” he says. “I can’t tell you how many different kinds of print media or electronic media or just things we tried.”

What he ended up with is one of the greatest coups in marketing history. Instead of Victoria’s Secret paying for television time, CBS reportedly pays Victoria’s Secret over $1 million a year for the rights to air what is essentially an hour-long infomercial. Last year, Taylor Swift belted out songs from a glittering runway while audience members like baseball superstar Robinson Cano and Maroon 5 lead singer Adam Levine gawked from the front row and millions more watched on TV.

![mg_78239_victoria_secret_280x210.jpg mg_78239_victoria_secret_280x210.jpg]()

The spectacle—really more a panty party than a fashion show—attracts more viewers than all other fashion shows combined. The impact mul- tiplies on social media, where the models are heavily followed. Aggre- gate its models accounts, and Vic- toria’s Secret has 33 million Twitter followers, more than Twitter itself.

Lots of things have changed in the 51 years since Wexner founded his business, none more so than Wexner himself. At the start of his career, he was working 90-hour weeks, leaving no time for anything else. Ask him what his favourite band or movie was from the 60s and 70s, and he shakes his head. “I don’t remember much about movies or music or what was going on,” he says. “By the time I was in my early 30s, I was enormously successful. And the more successful I was in terms of business achievement and accumulation of income, the more ineffective, unhappy I was.”

As the company grew, people started to tell him he was a great leader. Wexner didn’t see it. He wasn’t tall. Wasn’t outgoing. Wasn’t particularly well-educated. Wasn’t even sure what a leader really was.

So he started reading, searching for lessons. After work, he would tear through biographies of Ameri- can icons like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and John D Rock- efeller. What he saw was that the greatest leaders had perspective, understood society—and didn’t work 90-hour weeks. “If you keep your nose to the grindstone, you don’t have any nose,” says Wexner.

He began searching for hobbies, on a billionaire’s budget. He wanted to see more of the world, so he commissioned a yacht worth some $200 million and named it, appropriately, Limitless. He went to art museums, picked out a few favourite artists like Degas, de Kooning and Picasso, and began amassing one of the largest art collections in the world. He eventually homed in on Picasso, buying as many of his works as possible (Forbes estimates his collection is worth $1 billion). He also liked cars, particularly Mercedes, Jaguars and Ferraris, and is said to have bought 100 or so initially, later settling on just red Ferraris built in the 1950s to mid-1960s. “That’s how I think,” Wexner says. “It’s kind of like panoramic vision and then zooming in.”

Wexner’s most enduring obsession is his quest to define leadership. He ploughs through 100 books a year—all non-fiction, mostly biographies—getting recommendations from friends like Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough. He claims to have read every book on George Washington written in the last 100 years. “I find him amazingly fascinating,” Wexner says. “George Washington founded the country—and he thought he could do better.”

After 51 years as CEO of his company, is Wexner thinking about retirement? He smiles. His wife first asked him to retire a decade ago, and investors have been asking him about succession plans ever since. (Wexner’s four children, the eldest of whom is still in college, are too young to run the business.) But as usual, he doesn’t give an absolute answer. Instead, he reaches to the papers sitting on his lap and hands me a copy of the poem “Youth,” written by an early-20th-century writer named Samuel Ullman.

“Youth is not a time of life it is a state of mind,” we read in silence. “Years may wrinkle the skin, but to give up enthusiasm wrinkles the soul… Whether 60 or 16, there is in every human being’s heart the lure of wonder, the unfailing child-like appetite of what’s next, and the joy of the game of living.”

Wexner looks up and grins. “If you start painting yourself into a corner, life starts shutting down,” he says. “There is always hopefully a next.”