No Poriborton!

The finance minister has through his staid Budget ensured the survival of UPA 2 for now. But at what economic cost?

How one rates the latest UPA Budget depends entirely on how one views the overall context. Do Manmohan Singh and Pranab Mukherjee represent two top-end batsmen, at the height of their powers leading their team out of a difficult situation? Or are they more like the tailenders trying to avoid getting out and batting for a draw.

As it turns out, Mukherjee’s Budget showed that it was the latter. The FM played safe right through. No bold, expansive drives in the form of major policy announcement. No adventurous shots like ramping up subsidies either. He just played in the ‘V’ with a dour straight bat and treated the Budget as a simple statement of account, leaving the heroics for another day—perhaps another person.

In fact, the day may actually be remembered more for the fact that India’s cricket legend Sachin Tendulkar finally scored his hundredth international century.

Most initial assessments suggest that the finance minister has ensured that the UPA government survives to fight another day. Frankly, the furor over the Railway Budget had toned down expectations among analysts.

Ironically, Pranab Mukherjee may have taken a gamble by trying to fix some nuts and bolts of the economy that could result in efficiencies if things go as per plan one that is intended to give the government enough headroom when it has to present a Budget next year heading into General Elections. However, this government has failed to implement its policies many times in the past and there is no reason to believe it can do so now. For instance, Mukherjee has put considerable faith in being able to put in place a technological backbone for GST (Goods and Services Tax) as well as the PDS system.

Much of the subsidy transfer is expected to happen directly with the help of Aadhaar, or the unique identification number (UID). However, the UID only authenticates the identity of a person and not the targeted person. That will still remain in the bureaucratic domain. The finance minister is also banking on these initiatives to be completed in time and the government being able to plug leakages.

Similarly, allowing infrastructure companies to borrow abroad is unlikely to kickstart road and port building overnight. Infrastructure expert Partho Mukhopadhyay of the Centre for Policy Research says that it is difficult to borrow abroad when markets are volatile. “I am a bit worried that they seem to be resorting to the ECBs [external commercial borrowings] for infrastructure. The big question is about long-term stable finance and such money comes only when you have a relatively stable inflation regime,’’ he adds.

Besides, borrowers would have to contend with the increasing perception of India as a country where the government’s word is not exactly etched in stone. The finance minister did not help the country’s cause when he changed laws with retrospective effect to bring transactions such as Vodafone’s acquisition of Hutch Essar under the tax ambit. “The crisis in investor confidence cannot be solved by changing a rate here or there. There is no clear direction or message for infrastructure in this Budget,” says Mukhopadhyay.

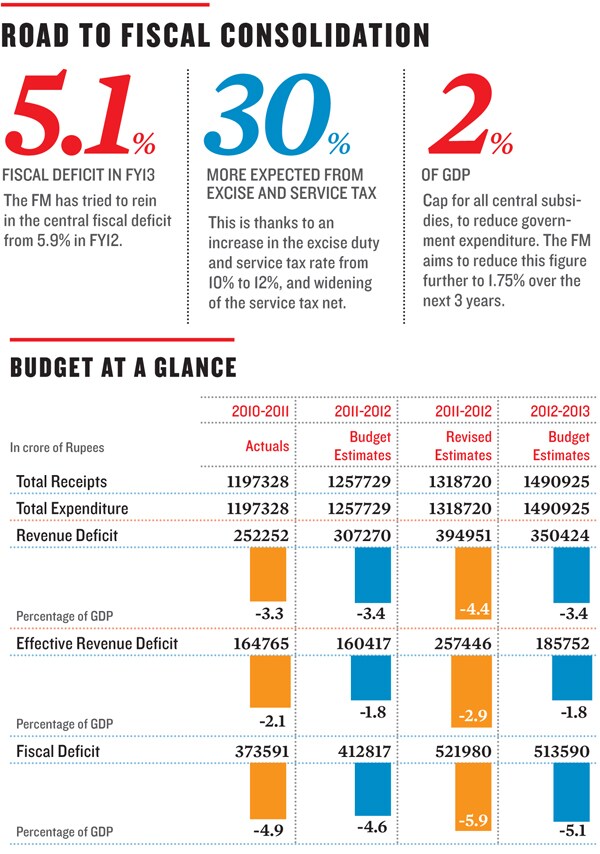

Going into the Budget day, the minister’s biggest worries were the burgeoning fiscal deficit, thanks to the decreasing industrial growth and increasing subsidy bill.

For subsidy, Mukherjee invoked the long forgotten FRBM Act and proposed to bring down the fiscal deficit by capping subsidies at 2 percent of GDP. But he came up with the caveat that henceforth only food subsidies would be fully funded by the government. As a result, if the overall subsidy bill of food, fertilisers and fuel crosses the 2 percent mark, the government would let the market prices prevail. That could lead to UPA 2’s nemesis—inflation—to rear its ugly head yet again. On the other hand, if under political compulsion, the government breaches its own 2 percent cap, it would impact the fiscal deficit, which in turn will lead to higher interest rates and inflationary pressures.

“In my opinion, he is underestimating the subsidies and this will lead to problems later on in the year,” says Samiran Chakraborty, head of research at Standard Chartered Bank.

That still does not explain why the FM chose to ignore the industrial slowdown that he himself acknowledged. The Economic Survey had also clearly identified industrial slowdown as being responsible for India’s growth deceleration. A senior political commentator says it is wishful to expect anything from the government after it gave in to its allies over the introduction of FDI in retail. “That set the pattern and it is difficult to see how the government could reverse it. I wonder if these guys even see the larger picture (globally)!” he says on condition of anonymity.

So, while hiking up excise and service tax rate was perhaps imminent given the fiscal deficit, there was little to encourage investment in industries, which were already hit hard by RBI’s relentless monetary tightening over the last two years.Sanjaya Baru, director for geo-economics and strategy at the International Institute for Strategic Studies and a former media advisor to the prime minister, agrees that Mukherjee’s Budget could turn out to be a gamble that hurts in the eventual analysis.

“See, the only political significant economic variable is inflation,” he says. He refers to the declining inflation in the run up to the 2009 elections, which UPA won with a surprising margin, to make his point. “As long as that is in control, no deficits matter,” he says.

But controlling inflation may not just depend on domestic factors. The quantitative easing in the US and the fear of a conflict involving Iran could continue to keep crude oil prices high.

It remains to be seen whether the Budget measures to improve investment in infrastructure or credit flow in agriculture will help India back on the high road of growth. But the FM may find it difficult to control inflation.

The Economic Survey had estimated that price rise in the coming months would moderate to 6.5 percent. However, that seems tough considering that excise duty hikes and service tax base increases would feed prices. The RBI managed to bring down inflation to some extent by raising rates. It is unlikely that this Budget has provided it with any room to cut them even though the credit policy review had indicated a softer-rate bias in the immediate future.

Besides, the government borrowing target is also substantially high at Rs 4.79 lakh crore, which means it would continue to compete with the private sector for scarce capital.

In a television interview, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said the government will have to bite the bullet on fuel prices and rationalisation of other subsidies.

“There is no other way,” Singh said. “There are compulsions of a coalition. We will consult all allies to take tough decisions.” That means petroleum product prices could be raised some time during the year, adding more fuel to the inflation fire and pushing the economy into further crisis.

A senior official told Forbes India that the government is too scared to take any decisive steps. It is desperately looking for a substitute for Trinamool Congress but there is no guarantee that a new ally will not be as populist as Mamata Banerjee.

Mukherjee started his Budget speech on a heroic note and raised expectations in the first 10 minutes by saying, “If India can continue to build on its economic strength, it can be a source of stability for the world economy and provide a safe destination for restless global capital… I know that mere words are not enough.”

In the end, Mukherjee did not even have words to take the country’s heart away! He may have survived the day, and if things work out he would have some fiscal space around the next Budget—which would be the last one before the 2014 elections—to boost Congress’s chances to retaining power.

However, if the gamble does not pay off, he would be stuck with a weakened economy, a worsened public sentiment and zero room to bring about a turnaround.

First Published: Mar 17, 2012, 11:20

Subscribe Now