Why the World Cup win is a watershed moment for women’s cricket

The victory has mainstreamed women’s cricket, shedding its identity as a tag-on to the men’s game—both as a sport and a marketing opportunity

Growing up in Mumbai, Jemimah Rodrigues never knew women’s cricket existed as an independent category. She used to knock around with her brothers and take throwdowns from her father till the latter decided she needed to be put through a structured practice routine. Along with her brothers, Rodrigues was sent to an academy, but was turned away. “It was because, first, I was a girl and, second, I was tiny. That hurt me a lot because, till then, I didn’t know you had to be a boy to play cricket,” Rodrigues told Forbes India in an earlier interview.

Rodrigues, now 25, still cuts a petite frame, but has a stature that towers over it. On October 30, at the DY Patil Stadium in Navi Mumbai, the No 3 batter overcame a loss of form to play an out-of-body innings, steering a record chase against Australia to take India into the final of the ODI World Cup.

The rest, as they say, is history. Three days later, India exorcised its demons of two near-misses—in the ODI World Cups of 2005 and 2017—and beat South Africa to lift its first-ever ICC trophy. And with it, Rodrigues and her colleagues settled a generational debate that they have been trolled with every time they felt short—that a woman’s rightful place isn’t in the kitchen, but wherever she desires, be it at the cricket academy, or, more fittingly, on the victory podium.

This, though, isn’t the first time Indian women have made sporting history. Recently, shooter Manu Bhaker became the only Indian athlete post-Independence to pick up multiple medals at a single edition of the Olympic Games—with two bronze medals from Paris 2024, while shuttler PV Sindhu raised the bar in badminton with medals from consecutive editions—a silver from Rio 2016 and a bronze from Tokyo 2020.

For cricket, too, this isn’t the first inflection point. “The turning point for women’s cricket in India came in 2017 when we played the final at the Lord’s Cricket Ground [in England],” says former captain Diana Edulji, the first Indian woman inductee to the ICC (International Cricket Council) Hall of Fame. “That match was telecast live, and it was a packed house at the stadium. Everybody started taking notice of women’s cricket after that.” Back then, Edulji was part of the Supreme Court-appointed Committee of Administrators (CoA), which was tasked with implementing the Lodha Committee reforms in the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) and that announced a ₹50 lakh incentive for each member of the team for making it to the final—which they would go on to lose to England.

So, what makes this 2025 ODI World Cup victory so seismic? Because this victory has finally put women’s cricket at a juncture where it can shed its identity of being a derivative of the men’s game.

“In India, there was limited understanding that women’s cricket needs to be viewed different from men’s,” says Prasanth Shanthakumaran, partner and head–sports sector, KPMG in India.

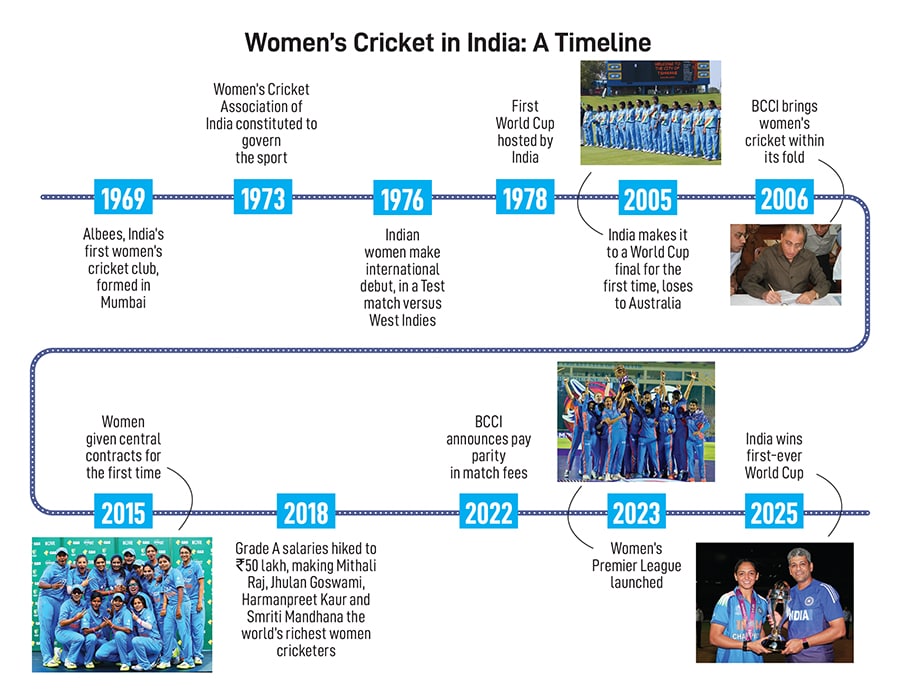

Consider their late start for example: Women’s cricket was brought into the BCCI fold only in 2006, when the Women’s Cricket Association of India, the governing body for the sport since 1973, was merged with the former. For perspective, this is just five years prior to India’s second men’s World Cup victory.

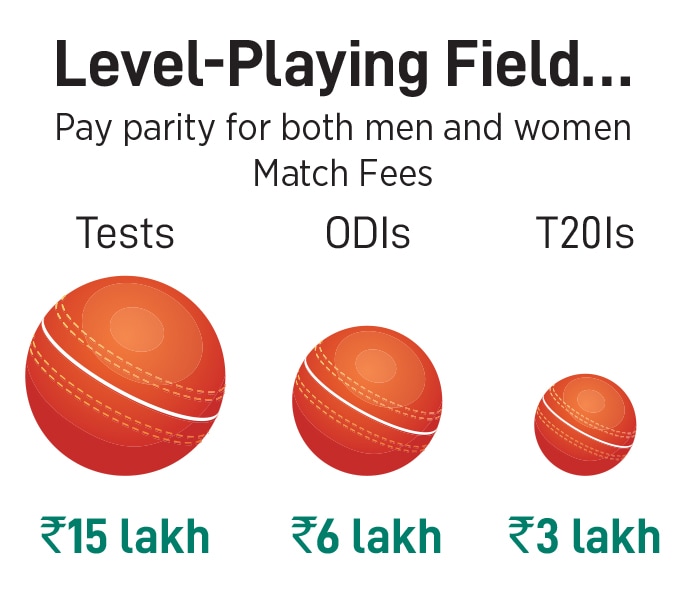

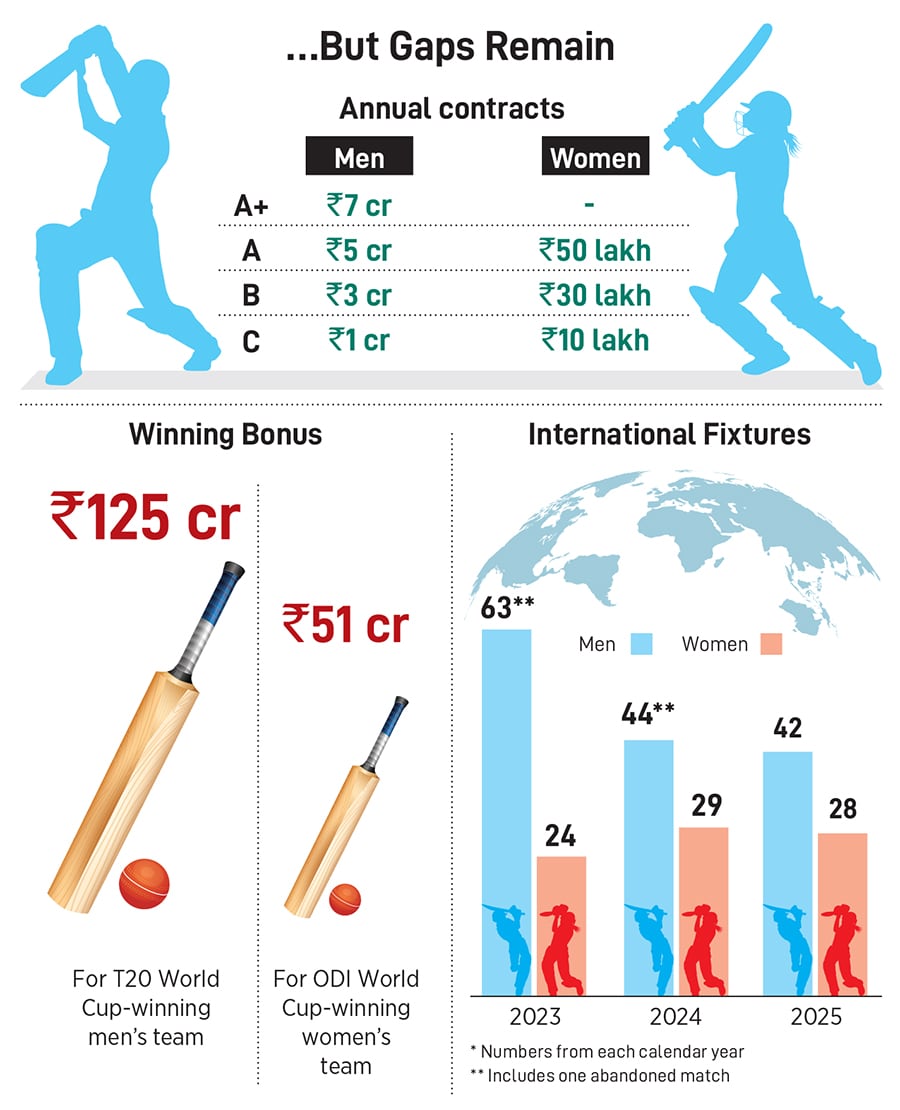

Besides, women cricketers were offered a central contract only in 2015, 11 years after their male counterparts; and while, in 2022, the BCCI brought in parity in match fees, a much-welcome move, there still remains a yawning divide between their annual fees: A Grade A-plus male cricketer earns ₹7 crore per year, compared to ₹50 lakh earned by a woman cricketer in Grade A, their highest bracket. Yet, the women’s team has consistently been benchmarked against the men’s team. “A constant comparison to men’s cricket has meant that women’s cricket was not as well received and lacked in its following. This World Cup has changed that perception. Women’s cricket has picked up a following and the followers now recognise that the two disciplines need to be viewed from two different lenses,” adds Prasanth.

Also Read: The innings after the World Cup final starts from zero: Shafali Verma

How the following has picked up and matched the men’s game is evident from the viewership numbers released by broadcaster JioStar: The 2025 tournament was watched by 446 million people on the streaming platform, surpassing the combined total of the last three women’s World Cups.

But the biggest validation of the fact that India is tuning into women’s cricket comes from the 185 million people who watched the final match, equalling the number for the men’s T20 World Cup final in 2024. “The tournament reach grew nearly 5x compared to the previous edition and total watch time jumped over tenfold. The India versus South Africa final became the most-watched women’s cricket match ever,” says Ishan Chatterjee, CEO-sports, JioStar. Of these, a record 92 million watched via connected TVs (CTVs), equalling the CTV audience for both the 2024 final as well as the 2023 men’s ODI World Cup final. It shows women’s cricket is no longer something people watch alone on phones, but in shared spaces like living rooms and pubs, deepening the adoption of digital, large-screen consumption and signalling a shift that once turned the Indian Premier League (IPL) into a community event.

“Cricket viewing in India has always happened in three buckets: 1) Fans of the game irrespective of teams and nations playing, 2) followers of India games, and 3) franchise-specific players. Now, all three buckets will have a sizeable representation of women’s cricket as well,” says Sanjay Adesara, chief business officer, Adani Sportsline, which owns the Gujarat Giants (GG) franchise in the Women’s Premier League (WPL).

In fact, the early signs of the growing popularity of the women’s game, both in terms of commerce and viewership, came from the WPL that was launched in 2023. The media rights and franchise sales for the tournament earned the BCCI ₹951 crore and ₹4,670 crore, respectively. The viewership numbers logged by the WPL, on the other hand, have seen a 142 percent year-on-year rise in TV, and a record of 103 million in the first 15 matches of 2024, up from 67.8 million in the first 14 matches of the inaugural edition. As a ripple effect, more and more girls have started to take up the sport as well—at GG’s training academy in Ahmedabad, there were hardly any girls three years ago; now they comprise a quarter of the trainees, says Adesara. India’s ODI World Cup victory is only expected to stoke the fire.

“So long as the support for women’s cricket was symbolic and was being celebrated because ‘even our girls did it’, commerciality was driven by perception. But once it can engage crores, it gets a solid commercial platform. The market will respect the women’s team for excellence, not gender. Once that starts to happen, you have broadcast reach,” says Shubhranshu Singh, a marketing veteran and the former head of marketing for Star Sports, who oversaw the launch of properties like the Pro Kabaddi League and led campaigns for ODI and T20 World Cups between 2014 and 2018. “This is where women’s cricket in India has finally moved from mere visibility to viability,” he adds.

All these mean that cricket has finally been able to catch the global upswing where, as a Deloitte study says, revenues for elite women’s sports are set to reach $2.35 billion in 2025—up from $1.88 billion last year and up 240 percent from 2022. As an example, at broadcaster JioStar, overall ad spends recorded a double-digit growth and partner outlays rose 3.5x when compared to the last edition. “The trajectory mirrors what men’s cricket saw in its early IPL years. The tide has clearly turned, and it vindicates our commitment to elevating women’s cricket much before it became a mainstream spectacle,” says Chatterjee of JioStar.

This surge has quickly translated from broadcast economics to individual athlete value, a trend reflected in a KPMG research that shows sponsorship revenues jump 30 to 40 percent globally with victory in a major sports tournament. No surprises that the World Cup win has already brought substantial off-the-field gains for key players like Smriti Mandhana, Rodrigues and Shafali Verma. The endorsement fees for Mandhana, India’s most prolific run-getter for the second consecutive year who has 16 brands in her portfolio, is expected to jump at least 25 percent from her current range of

₹2-2.25 crore.Rodrigues, who played a definitive innings of 127 not out in the semifinal against Australia, has jumped from ₹60 lakh per brand from before the tournament to around ₹1.5 crore now, while Verma, who came in as a replacement for injured batter Pratika Rawal before the semis and walked away with the Player of the Final trophy, is expected to fetch crore-plus per endorsement from ₹40 lakh earlier, says Divyanshu Singh, the CEO of JSW Sports that manages the two athletes. Industry insiders estimate that the endorsement fees for keeper-batter Richa Ghosh—who played a cameo in the final—too, will double from her current ₹25 lakh or so.

“In India, new heroes have been born. And as we create new heroes, it starts a sporting movement. Like the 1983 World Cup win started for male cricketers, or Neeraj Chopra’s Olympic gold, or Sindhu’s medals started for individual sports, we expect this to happen to women’s cricket now,” says Singh.

Adds Tuhin Mishra, founder of Baseline Ventures that represents the likes of Mandhana and Ghosh: “The biggest thing for the brands is also that women’s cricket is now seen on TV. In the last few years, the BCCI has ensured that an increasing number of international matches as well as the WPL gets televised. Every news channel has also covered the World Cup, and should continue to do this.”

Even at the team level, the tenor of the conversations has changed. Says Jinisha Sharma, the director of Capri Sports that owns the UP Warriorz franchise in the WPL: “Before the World Cup, we were reaching out to brands, explaining why women’s cricket was worth their attention. On the day of the final, those same brands were calling us not because the product changed, but because the perception did. People are finally seeing what we’ve always believed in.” The meagre 5 percent contribution that India’s women athletes made to the overall endorsement pie last year—as mentioned by Vinit Karnik, MD-content, entertainment and sports, WPP Media South Asia, in his recent column for Exchange4Media—is set to skyrocket soon.

“But, women’s sports business isn’t just sponsorship play,” says Prasanth of KPMG India. “It’s a larger athlete engagement play. When women athletes win, their social media footprint typically shoots up 60-70 percent, in some cases even 100 percent.” Rodrigues’s Instagram following, for example, has doubled from 1.5 million to 3.4 million post the World Cup, while Verma’s has shot up from 550,000 to 860,000, as of November 7. “Social media engagement triggers the athlete economy—the ecosystem around athletes that includes custom products, endorsements, leagues, sporting events, media coverage—all of which fuels the broader business of sport economy, and this isn’t limited to cricket,” adds Prasanth. The World Cup win is set to provide a major fillip to India’s athlete economy pegged at ₹6,800 crore in 2024-25.

Also Read: 2017 World Cup was the turning point for women's cricket in India: Diana Edulji

The surge in athlete equity isn’t confined to the marquee names alone. The World Cup victory has catalysed recognition beyond the likes of Harmanpreet Kaur, Mandhana and Rodrigues—visibilising the likes of, say, Deepti Sharma, who has always fallen under the radar of marketers despite a string of solid performances. “For those who aren’t endemic to the sports industry, this World Cup has been a watershed moment,” says Shreya Sachdev, head of marketing at Puma India, which has Kaur, Ghosh and Sharma as brand ambassadors. “Brand value quadruples and compounds when you don’t have to explain who the person in the advert is. This is a massive unlock and the reason why we will see the brand value of women’s cricket massively going up. Women cricketers always had credibility, and those of us in the industry have always known they were worth investing in. For those on the outside, now they have demonstrated the commerciality,”

As lower-profile cricketers gain visibility, brands now have the opportunity to tap into newer catchment areas beyond the metros. Recent industry data by logistics intelligence platform ClickPost shows that 74.7 percent of online shopping this Diwali came from non-metros, or ‘Bharat’—an audience that would identify with Punjab girl Kaur’s candid confession on TV that she isn’t comfortable speaking in English.

“You will see a lot more regional brands that will use vernaculars and leverage the authenticity of these cricketers,” says Singh, formerly of Star Sports. “Now, you are going to get a relevant audience.” Adds Sachdev of Puma: “If a brand is just going to use them as a face on a billboard, they’re not leveraging the goldmine of storytelling that you can do through them and their experiences.”

In some ways, that journey has already begun, where some of the WPL teams are starting to see a shift in brand partnerships that are looking to go beyond a spot on the jersey. RR Signature, a premium fans and lighting brand under the RR Kabel group that bought the front-of-jersey sponsorship slot (the most premium real estate on a player’s shirt) for UP Warriorz last year, invested further in cross-promotions with co-branded advertisements, packaging etc. “It was a new realm in brand partnerships,” says Sharma of Capri Sports. “That apart, I won’t be surprised if we see more women-centric brands come forth next year to partner with the team. We have already started some of those conversations.”

But one of the ICC’s key associations has also shown how women’s cricket has thrown open avenues beyond just women-centric brands. In August, Google signed a women’s-only global partnership with the ICC to enhance fan experience, breaking down the perception that only the likes of cosmetics and apparel brands will chase women’s sports because of their gendered appeal. One of their biggest advertisements came in what can easily be among the most abiding frames of the tournament—of Rodrigues lying prone on the field and clicking a selfie on a Google Pixel, with the entire team in the background. Even JioStar saw a lineup of categories like infra, tech, BFSI, consumer durables etc that are traditionally associated with men’s sport. “Brands are no longer treating women’s cricket as a ‘CSR story’. They are buying exclusive women’s cricket inventory, rather than packaged deals with men’s. Over 55 percent of brands came exclusively for the Women’s World Cup,” says Chatterjee of JioStar.

“We have observed that more than 60 percent of sports lovers are gender-agnostic,” says Prasanth of KPMG India. So, if a brand wants to address the next generation of sports lovers, they will have to recalibrate their storytelling instead of trying to forcefit women athletes into a preconceived persona. “Brands should not box female athletes into a particular category of products and should expand their thinking, as they have done with male athletes.” he adds.

How does one sustain the momentum after the euphoria fizzles out? The next frontier for the women would be to convert moment marketing—how Surf Excel, for instance, played on Rodrigues’s muddied jersey the day after her heroic innings—into a movement of marketing. “Now is the time for brands to walk the talk,” says Mishra of Baseline Ventures. “The inspirational stories of the girls would give brands great RoI [returns on investment]. Most of them have come from humble backgrounds and fought great odds. Look at Smriti, who comes from Sangli, a city that doesn’t even have an airport, or Richa from small-town Siliguri in the north of Bengal.”

The onus is also on the players to keep the conversation going. The WPL is scheduled in February, while the T20 World Cup will take place in England in 2026. And 32 months down the line would be the crowning glory—the Los Angeles Olympics where cricket will make its debut. A strong performance at each of these will only amp up viewership and pull in more investments, helping bridge the endorsement gap between top male cricketers that can be anywhere around

₹6-7 crore per brand to that of women (around ₹2.5 crore).It’s perhaps time for the BCCI, too, to take the next step of giving the women a hike in their annual fees. The ₹50 lakh stipulated for Grade A cricketers has remained stagnant since 2018; doubling it would be a reasonable ask. “One World Cup won’t fix everything, but it has sparked a belief. And belief changes everything,” says Sharma of Capri Sports.

When Mandhana played gully cricket in Sangli, she was the designated limbu-timbu (weak link, in Marathi), a metaphor that could be extended to her sport in general. Now, the tables have turned.

First Published: Nov 25, 2025, 11:39

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Nov 28, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)