How private equity is fuelling the transformation of health care in India

Global PE firms are pouring billions into hospital chains in India, upending the established hierarchy and enhancing governance and accountability

Dr BS Ajaikumar, when he was a practising oncologist in the United States, set up a not-for-profit cancer hospital in Mysuru in 1989. Fourteen years later, he moved to India with his family to start Healthcare Global Enterprises (HCG), which had a hub-and-spoke model for cancer care in India with the hub being in Bengaluru.

HCG picked up pace when private equity (PE) began to flow into it, beginning with `50 crore from IDFC Private Equity in 2006. Three PE deals took place between 2006 and 2008, and one each in 2010 and 2013.

A big one came in June 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic took a grip over the country, when CVC Capital Partners invested Rs1,049 crore for a shade above 60 percent equity. And this year, KKR paid Rs3,200 crore for a 51.5 percent stake.

Along the way, HCG has become a veritable lab for PE’s experiments with Indian health care. And what an experiment it is turning out to be.

“It is the PE money that is fuelling the growth of health care in India. Otherwise, hospital chains like HCG would not have seen the kind of scale that it has today,” says Ajaikumar, founder & chairman, HCG.

Indeed, global PE firms Blackstone, Temasek, TPG, General Atlantic, KKR and others are pouring billions into hospital chains in India, upending the established hierarchy. The most recent deal is Manipal Hospitals’ acquisition of Sahyadri Hospitals from Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan in July. Valued at approximately Rs6,000 crore, this adds 11 hospitals across Maharashtra and brings Manipal’s total bed count to 12,000.

Manipal now leads the pack in terms of bed capacity, surpassing Apollo Hospitals, which has more than 10,000 beds across 73 hospitals.

Earlier, in April 2023, Temasek Holdings acquired a 59 percent stake in Manipal Health Enterprises for $2 billion, becoming its majority shareholder. The deal involved buying out stakes from the existing investors, including TPG and National Infrastructure Investment Fund (NIIF).

Aster DM Healthcare merged with Blackstone-backed Quality Care India Limited, forming Aster DM Quality Care Limited. The merged entity ranks among India’s top three hospital chains, with 38 hospitals and more than 10,366 beds. Blackstone holds a 30.7 percent stake in the new entity, and Aster promoters 24 percent.

“Life sciences and health care are key investment themes for Blackstone. We have been investing in the sector with a buy-and-build thesis over the past year. We take pride that we have created the second largest hospital platform in India in less than two years through our business builder approach,” says Ganesh Mani, senior managing director, Blackstone.

And there is more to come. “We have an organic bed addition plan for the combined entity that takes us to over 13,000 beds in a little more than two years. We will also evaluate inorganic opportunities as they arise... we will be open to evaluating inorganic opportunities pan-India,” says Mani.

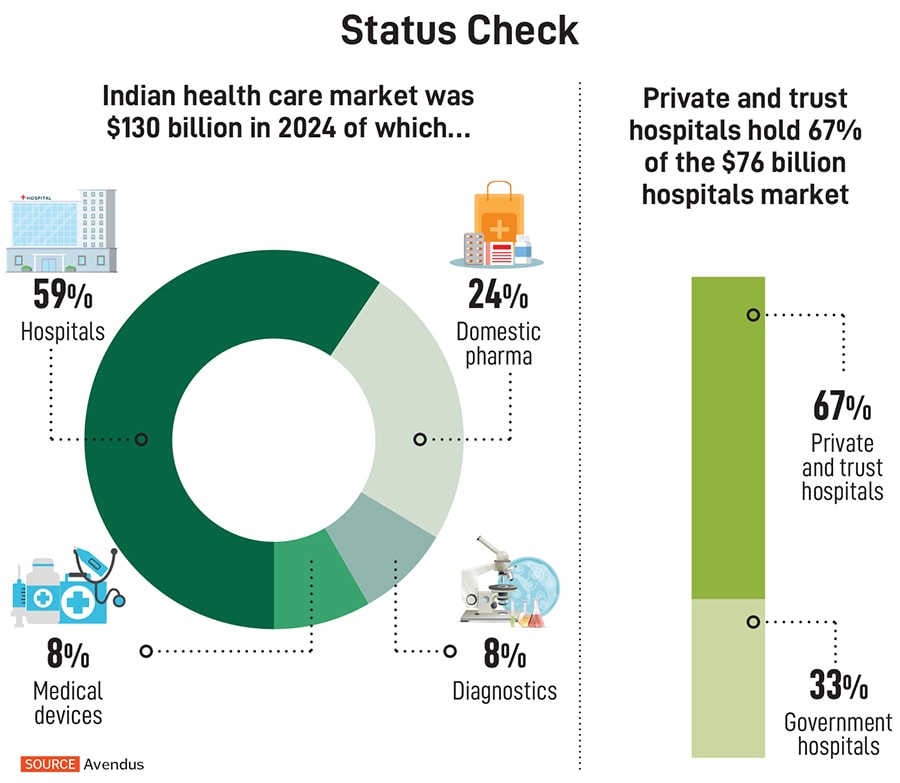

From 2022 to 2024, India’s health care and pharma sector saw 594 M&A and PE transactions worth over $30 billion. Hospitals alone accounted for nearly 40 percent of those deals, according to a report by Grant Thornton Bharat and the Association of Healthcare Providers of India (AHPI).

“Low public health care spending, increasing private consumption, and expanding insurance coverage are creating space for private investment,” says Bhanu Prakash, partner and health care services industry leader, Grant Thornton Bharat.

The reasons are layered: A rising demand for quality care, surge in chronic illnesses, deeper insurance coverage and a shift toward value-based models. Add to that the post-pandemic urgency to upgrade infrastructure and a widening gap between demand and supply.

For hospital chains, the influx of capital is not just about expansion, it is also about strategic partnerships, asset monetisation and operational efficiency. As India positions itself as a global health care hub, hospitals are no longer just places of healing, but also emerging as high-yield investment platforms.

The impact of PE money, though, goes beyond the yield. “PE has played a transformative role in shaping Aster’s growth journey, particularly in strengthening our governance framework,” says Azad Moopen, chairman, Aster DM Healthcare. He adds: “Since partnering with PE investors, Aster DM Healthcare has achieved measurable improvements across both financial and operational metrics.”

PE firms are bringing in more than just money. They are introducing robust corporate governance, clinical accountability and strategic discipline. Independent boards, clinical audits and outcome tracking—once rare in Indian hospitals—are now increasingly common.

“There’s often a misconception about PE investing, especially in India. It’s about adding value, rather than taking it away,” says Varun Talukdar, principal at General Atlantic. The firm in April 2024 invested in Ujala Cygnus, a leading health care provider in Northern India with a network of 21 hospitals serving Tier II and III cities. “Some might use different models in mature markets, but it is not what we do in India—a growth market in health care. So, you can’t apply a cost-cutting approach to businesses that are underinvested and need to scale,” he adds.

In India, a growing number of individuals are returning to their hometowns to build hospitals and improve health care access. Though well-intentioned, these facilities often face challenges of limited investment in infrastructure, weak clinical standards and reliance on a single specialist. As a result, the care provided is rarely comprehensive.

This is where the PE firm comes in.

“These hospitals already have a level of establishment—a brand, a connection with the community and strength in one specialisation. We invest in upgrading that infrastructure. For example, many of these facilities have outdated operating theatres (OTs). We replace them with modern modular OTs equipped with proper air filtration and sterile environments,” explains Talukdar. “Clinical quality isn’t just about having the right equipment, it is also about having the right systems, people and mindset. And that is what we are building.”

The National Accreditation Board for Hospitals & Healthcare Providers (NABH) is India’s benchmark for hospital standards. Of the estimated 70,000 hospitals in the country, only 1,200 to 1,500 are NABH-accredited, states Talukdar.

In 2012, Advent International acquired a controlling stake in CARE Hospitals, helping expand its footprint and streamline operations before exiting in 2016. Shweta Jalan, managing partner at Advent International, says, “We bought businesses with strong fundamentals and transformed them from single-founder-led to professionally managed companies, putting in place strong management teams and boards, effectively becoming high-governance, large listed companies.”

More recently, in 2024, Advent acquired a minority stake of 12.1 percent in Apollo HealthCo, for Rs2,475 crore, which is now undergoing a demerger. “In an era where digital penetration in the country is over 70 percent in some states and 95.15 percent of villages have access to the internet, the investment will help accelerate the expansion of our omnichannel digital platform, Apollo 24x7,” says Suneeta Reddy, managing director, Apollo Hospitals.

Digitising health care is increasingly becoming a priority—reducing manual errors and improving clinical outcomes. “We are currently piloting an AI (artificial intelligence)-based clinical decision assist tool at Ujala Cygnus hospitals. During an OPD consultation, the tool listens to the conversation between the doctor and patient, and based on the symptoms and case history, generates diagnostic suggestions,” adds Talukdar of General Atlantic.

Amit Varma, managing partner at Quadria Capital, believes PE does not make health care more expensive. “In India, you can’t survive unless you follow one mantra: Serve the largest number of patients at the lowest possible price. And you must deliver the best possible quality,” he says. Varma says Ayushman Bharat could be a big step in this direction.

At its heart, health care is about the human touch—about healing, empathy and trust. For instance, Ajaikumar says he has championed a culture of accountability at HCG, conducting mortality audits for every death and pushing for continuous improvement. “In 2017, our mortality rate was 2.83 percent with 5,500 discharges. Today, with 13,500 discharges, it’s down to 0.9 percent,” he says.

Yet, as promoter stake has dropped from 85 percent to 10.88 percent, he reflects on the trade-offs of scaling with PE. “We decided to first take money from PEs simply to scale up,” he admits. “Maybe I should have just stuck to five hospitals.”

Once considered niche, single-specialty hospitals in India are emerging as a formidable force. “When we started, the concept of single-specialty hospitals was practically unheard of. A hospital was expected to treat everything,” says Ajaikumar. “But today, I can say with confidence: if you want timely and effective cancer treatment, you must go to a dedicated cancer centre.”

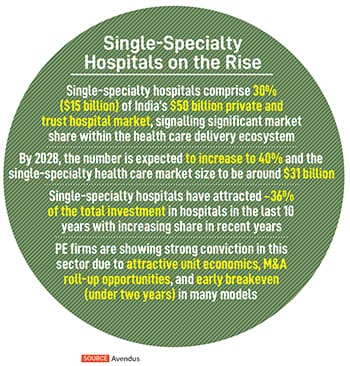

Single-specialty hospitals’ share in the private health care market has grown from 20 percent in 2019 to 30 percent in 2024, and is projected to reach 40 percent by 2028, representing a market size of $31 billion, says an Avendus report. This surge—driven by a 19 to 20 percent CAGR—reflects a shift in investor and patient preference.

“Single-specialty chains have seen steady momentum, supported by efficient operations, faster break-even potential and focussed health care delivery,” says Prakash of Grant Thornton Bharat. Between 2022 and mid-2025, more than 50 single-specialty hospital deals were recorded, accounting for a growing share of total hospital transactions by volume. Segments like IVF, oncology, nephrology and eye care have seen recurring investment.

Experts estimate that setting up a single-specialty facility typically costs upwards of `5 crore, whereas a mid-tier, 100-bed multi-specialty hospital can require Rs30 crore or more.

Quadria, for instance, has backed both multi-specialty and single-specialty hospitals. But over time, its focus has shifted toward single-specialty. “Instead of spreading resources across 20 specialties, concentrating on one enables deeper specialisation, more targeted technology investments, and streamlined procurement,” says Varma. Investments in Maxivision (ophthalmology), NephroPlus (dialysis), and AIG (gastroenterology) reflect this strategy. AIG, for instance, handles more than 3,000 OPD patients every day at affordable rates—Rs100 to Rs1,000 per visit—while remaining one of Quadria’s most profitable assets.

“Single-specialty is where multi-specialty was 10 to 15 years ago; it is just beginning to get organised. Secondly, unlike multi-speciality, single speciality is more like a consumer retail model, with smaller clinic sizes,” explains Anshul Gupta, managing director and head, Healthcare Investment Banking, Avendus Capital. He expects many more IPOs coming from single specialties in the next few years.

Health care is so attractive to investors, especially in India, because of its high growth potential. Another compelling aspect is how health care brands are built. Globally, they take generations to establish. “In India, because health care started from relatively low standards of quality, there is an opportunity to build a trusted brand much faster simply by focusing on quality. You could, for example, run a hospital focussed on clinical excellence and not on short-term profit to build a brand that people will trust for decades,” adds Talukdar.

India’s hospital landscape is shaped by regional brands that serve far beyond their geographies, thanks to natural patient “drainage patterns” from underserved areas to trusted centres of excellence. Hospitals like Medanta in Gurugram, and KIMS and Apollo in Hyderabad have become magnets for patients across states.

Investors are leveraging this trust by acquiring strong local brands—like Ujala’s expansion into Punjab via Amandeep Hospitals.

“One of the biggest misconceptions is that India is a homogenous market. The core challenges in health care—infrastructure, skilling and affordability—are consistent across regions. But how you address them must be tailored to each geography,” explains Varma of Quadria Capital.

While regional brands will continue to exist, experts believe the broader trajectory of Indian health care is headed toward consolidation. “Insurance, capex efficiency and procurement leverage are the three big reasons,” says Varma. Insurers prefer hospital networks with geographic spread, making large chains like Apollo, Fortis and Manipal more attractive. Bigger players benefit from economies of scale—whether negotiating equipment prices with vendors like Siemens or securing better rates from pharma companies like AstraZeneca. “Scale isn’t just beneficial, it is also essential for sustainable growth,” Varma adds.

India spends only 4 percent of its GDP on health care, which is relatively low compared to global benchmarks. All the consolidated hospital chains and PE deals together account for just 2.5 percent of India’s total hospital beds. India has 70,000 hospitals and 2 million beds for a population of 1.4 billion. Most of this infrastructure is concentrated in urban centres. Clearly, there is a gap.

Close to 70 percent of health care in India is delivered by the private sector, but the private sector only owns 30 percent of the infrastructure. Additionally, there isn’t enough skilled workforce—doctors, nurses and technicians. Varma says: “Today, only 30 percent of patients are covered by public or private insurance. That means 70 percent of Indians are still paying out of pocket for their health care needs. This is perhaps the most critical challenge.”

After the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in public-private partnerships and government investing in health care—especially with schemes like Ayushman Bharat. Adds Varma: “I genuinely believe we’re entering a new phase.”

First Published: Sep 08, 2025, 13:13

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Sep 05, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)