The unheard story behind Amitabh Bachchan's baritone

With a voice that needs no introduction, Amitabh Bachchan has enthralled audiences as a singer and voice artiste for five decades

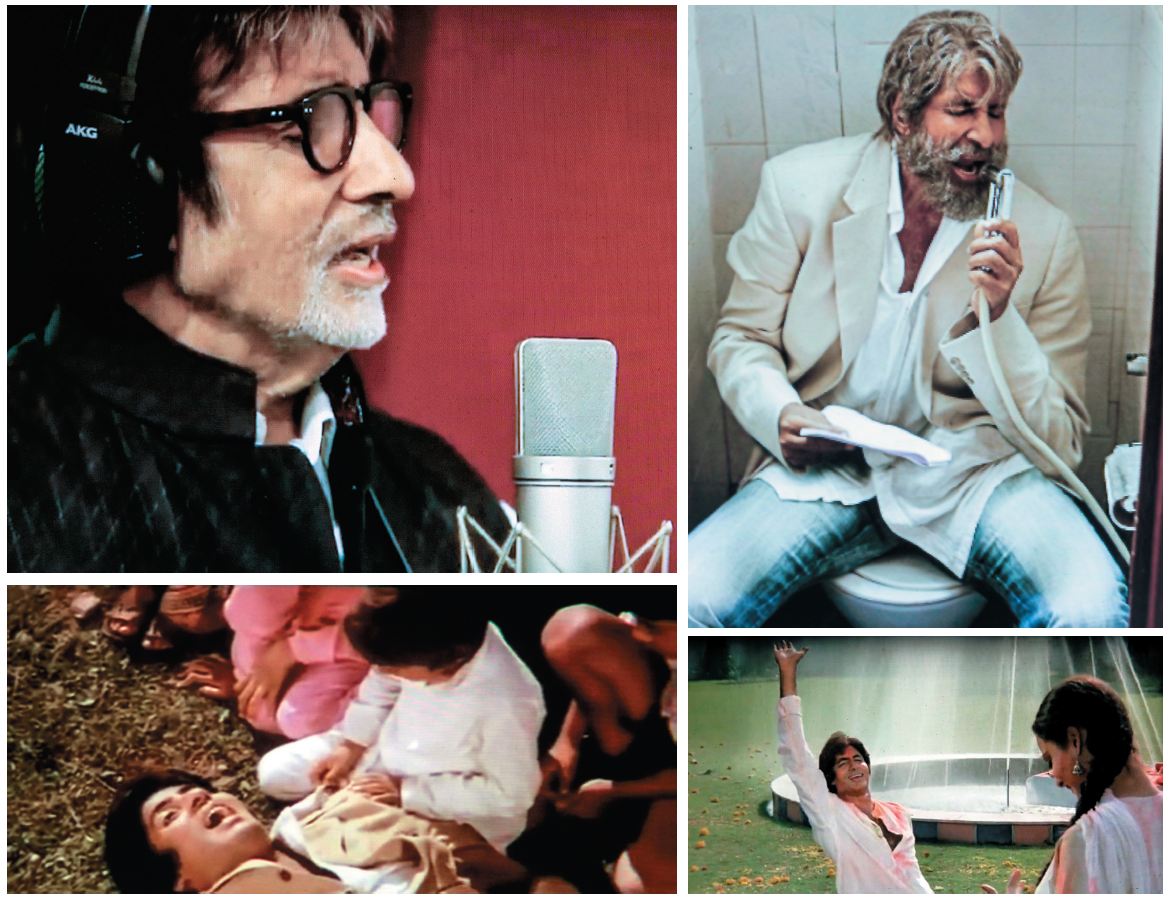

(Clockwise from left, facing page) Bachchan has sung for films like Wazir, Shamitabh, Silsila and Mr Natwarlal[br]Early in November, celebrations broke out to commemorate 50 years of Amitabh Bachchan in the Hindi film industry Saat Hindustani, directed by Khawaja Ahmad Abbas, had released on November 7, 1969. What went unsaid was the fact that the date marked his acting debut, and not his actual debut in the world of cinema. For that had taken place about five months earlier, in May 1969, when Mrinal Sen’s film Bhuvan Shome was released. It was the first time that Bachchan’s name appeared in the opening credits of a film—after a list of acknowledgements, the names of the film, author, screenplay writer and production house—and that too as simply ‘Amitabh’. He was the story’s narrator.

(Clockwise from left, facing page) Bachchan has sung for films like Wazir, Shamitabh, Silsila and Mr Natwarlal[br]Early in November, celebrations broke out to commemorate 50 years of Amitabh Bachchan in the Hindi film industry Saat Hindustani, directed by Khawaja Ahmad Abbas, had released on November 7, 1969. What went unsaid was the fact that the date marked his acting debut, and not his actual debut in the world of cinema. For that had taken place about five months earlier, in May 1969, when Mrinal Sen’s film Bhuvan Shome was released. It was the first time that Bachchan’s name appeared in the opening credits of a film—after a list of acknowledgements, the names of the film, author, screenplay writer and production house—and that too as simply ‘Amitabh’. He was the story’s narrator.

The trajectory and nuances of Bachchan’s career as an actor are the stuff of legend within the country’s entertainment industries. Listing the names and number of awards and accolades that he has received over the past five decades is perhaps superfluous, given the position he has come to occupy not only within the film fraternity, but also in the hearts and minds of many millions of viewers and fans.

And if there is one element of his persona—that larger-than-life, invincible, indefatigable persona—that has helped seal his position in the consciousness of the masses, it’s his voice. That rich baritone that needs no face to be recognised.

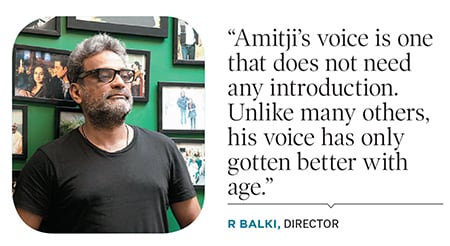

“Amitji’s voice is one that does not need any introduction, any definition,” says R Balakrishnan, popularly known as Balki, who has directed Bachchan in three films, including Shamitabh, which was dedicated to his voice. “Unlike many others, his voice has only gotten better with age.”

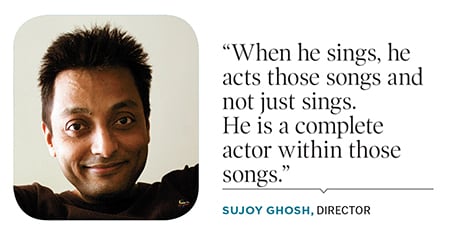

“When Amitabh Bachchan talks, everyone listens to him,” says director Sujoy Ghosh, in whose film Kahaani (2012) Bachchan sang ‘Ekla Chalo Re’, the much-loved song penned by Rabindranath Tagore. “That is why I thought that if he sings, people will also listen to him.” Bachchan produced an album Aby Baby in 1996, with music by music producer Bally Sagoo[br]

Bachchan produced an album Aby Baby in 1996, with music by music producer Bally Sagoo[br]

*****Bachchan’s initiation into the Hindi film industry can perhaps, in some strange way, be attributed to Ameen Sayani—he of the golden voice that enthralled listeners for decades with Binaca Geetmala, a weekly countdown programme of Hindi film songs that was first broadcast on Radio Ceylon (1952-88) and then on All India Radio (1989-94). A few years ago, while talking to Forbes India, Sayani had recalled how Bachchan—then an unknown newcomer—had come to the radio station for a voice audition, without an appointment, in the late 1960s. But Sayani, caught up with about 20 shows a week, had no time to spare for the lanky fellow.

It is, of course, now a matter of amusing speculation to imagine what might have happened of Bachchan’s acting career if Sayani had taken time out for him.

It was during these years of struggle that Bachchan had then approached director Mrinal Sen for the job of a narrator in Bhuvan Shome, and had luck favour him his voiceover introduced viewers to the film’s eponymous protagonist, played by Utpal Dutt. But despite getting more acting roles after the release of Saat Hindustani (1969)—with Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anand (1971) shining a definitive spotlight on Bachchan’s acting prowess despite the overwhelming presence of reigning superstar Rajesh Khanna—Bachchan continued his parallel career as a voice artiste.

In 1972, he was the narrator in Mukherjee’s Bawarchi, which also starred Khanna, where he introduces not just the chaotic household of Shanti Niwas, but also—in a unique credit roll of sorts—the makers of the film, much like the sutradhar of a play that is about to unfold on stage. This was followed by Tarun Majumdar’s Balika Badhu (1975), where he lent his voice to the character of Amal.

Between 1972 and 1975 came a handful of films that set Bachchan firmly on the highway to acting stardom: Zanjeer, Abhimaan and Namak Haraam released in 1973, Majboor in 1974, and Deewar, Sholay, Chupke Chupke and Mili in 1975. And so, from being the voice of faceless narrators, Bachchan’s voice became indomitably his own. One that the audience came to identify as an integral part of the angry-young-man image that he championed on screen.

*****Starting from the late 1970s, Bachchan’s career as a voice artiste found a new channel of expression, thanks to his acting stardom—through film songs. The first of these was in Mr Natawarlal (1979), followed by songs in Silsila and Lawaaris (1981). The songs remained hits for years after the films had faded from popular memory. ‘Rang Barse’ from Silsila, penned by Bachchan’s father, poet Harivansh Rai Bachchan, in particular continues to be a crowd favourite, close to 40 years later.

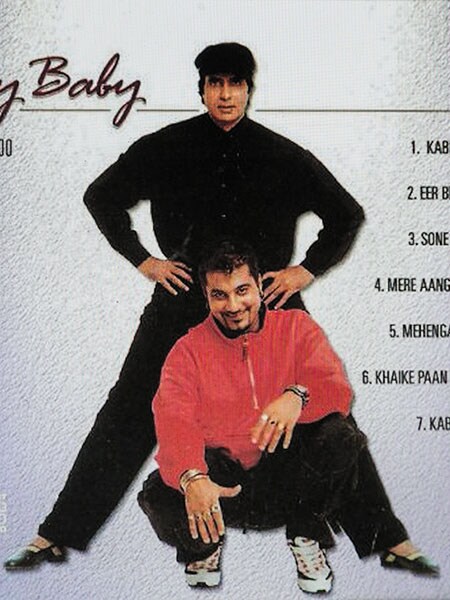

After these years of intermittent experiments with singing came the step that was meant to establish Bachchan as a singer in his own right. Riding on the emergence of Indian pop music—those were the years in a newly liberalised economy when the country was experiencing music channels such as MTV and Channel V, and a new phenomenon called FM radio—Bachchan produced his first music album Aby Baby in 1996, under his audio company Big B Records, with music by Bally Sagoo.

“It was Mr Bachchan who approached me for the album,” recalls Sagoo, the British-Indian music producer who had burst onto the British mainstream pop music scene of the 1990s with his reworked versions of Hindi film classics. “He was clear about the kind of sound he wanted for the album he said that it should sound international. He is a musically minded person and listens to a wide range of music, from Motown to jazz.”

The album had seven tracks, including a new version of ‘Kabhie Kabhie’ (from the 1976 film of the same name) sung by Sadhana Sargam, interspersed with poetry recited by Bachchan there were the remixed versions of ‘Khaike paan Benares wala’ (from Don, 1978), and ‘Mere angne mein’ (from Laawaris). “Mr Bachchan was clear that he wanted to work with his father’s poetry, which we had in ‘Eer Beer Phattey’,” adds Sagoo. “I had only one condition: That we will record in my studio in London.” He recalls how readily Bachchan moved to his London studio, and the many weeks that they spent together, jamming and creating music. “It was quite incredible how he did it,” says Sagoo. “We were working together, having fun, ordering pizza.”Two of the album’s songs were made into music videos, with ‘Eer Beer Phattey’—“this is a story about four guys” as Bachchan narrates in the song—gaining much popularity on music channels. Choreographed by Raju Sundaram and directed by Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, the video was slick and stylish, with choreography, animation and music that was at par with any global hits of the times. But, Aby Baby remained one of its kind.

Despite singing along with bhangra-king Daler Mehndi in his film Mrityudaata (1997), and later with pop singer Adnan Sami in his 2002 album Tera Chehra, Bachchan never produced another album of his songs.

*****

Bachchan’s acting career, which had been flagging by the end of the 1990s, made a dramatic comeback with the turn of the millennium, with a series of hit films such as Mohabattein (2000), Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham and Aks (2001), Aankhen and Kaante (2002), Baghban (2003), Khakee and Dev (2004), and Black (2005). Where his onscreen persona was concerned, he had finally transitioned from his angry-young-man image—one that he was struggling to hold on to by the end of the ’90s—to that of an older, more mature, more dignified, salt-and-pepper-haired patriarch. Coupled with the runaway success of Kaun Banega Crorepati, the TV game show that began in July 2000 and in which he played this new-found image to the hilt, Bachchan was back to doing what he did best. Charm.

Along with this resurrection of his acting career, came Bachchan’s second innings as a voice artiste. “San 1893. Champaner. Desh ke beecho beech basaa ek gaon [The year 1893. Champaner. A small village located in the middle of the country],” began his narration of the 2001 Aamir Khan blockbuster Lagaan. Quite like the sutradhar of Bhuvan Shome and Bawarchi, but the pitch of his voice was now several notches lower, and had a demeanour that was more like the ‘voice of god’ rather than the guy next door. This was followed by his narrations in Pradeep Sarkar’s directorial debut Parineeta (2005), and Ashutosh Gowarikar’s 2008 historical epic Jodhaa Akbar.

By this time, Bachchan’s voice and association with a film was beocming much more than just a narration. Explaining why he agreed to work for Parineeta, he said in a 2009 interview that when Vidhu Vinod Chopra, the film’s producer, showed him scenes from the film, he was filled with nostalgia. “I had been a resident of Calcutta for some years. The film was set in 1962, and it was around the same time that I had gone to the city to look for a job. The scenes I saw made me nostalgic because they showed Calcutta the way it really used to be. The scenes had captured the city beautifully.”

In the past decade, Bachchan has lent his voice to eight films—the latest being Sankalp Reddy’s The Ghazi Attack (2017)—along with singing more songs in films in which he has acted, including Wazir (2016) and 102 Not Out (2018). “Amitji has a keen ear for music,” says Ghosh, “and can also play the sitar and the piano. My respect for him as a singer had gone up several notches when he had sung the rap section—‘1 o’clock in my house’—which was part of the ‘Jahaan chaar yaar’ song in Sharaabi (1984). When he sings, he acts those songs and not just sings. He is a complete actor within those songs.”

“Initially I had not thought of whom to approach for the voiceover,” says Reddy, the first-time director of The Ghazi Attack. “Rana Daggubati, who acted in the film, was the one to suggest that we approach Mr Bachchan, and it was he who went to meet him.” The fact that Bachchan agreed makes Reddy feel that he hit the jackpot. “In my first film itself I got three superstars—Mr Bachchan, Chiranjeevi [who did the voiceover for the Telugu version], and Surya [who did the voiceover for the Tamil version].”

“It is the way in which he modulates his voice that makes so much of a difference,” adds Reddy, a fan of Bachchan ever since he watched Khuda Gawah (1992) as a schoolkid on the big screen and was captivated by the intensity of his voice.

Representing this fascination that audiences have had over the decades with Bachchan’s voice was Balki’s film Shamitabh. “The film was meant to do justice to his voice,” says the director who also made Cheeni Kum (2007) and Paa (2009). “His voice has a gravitas, and he is able to modulate it in any way, even adding comic touches when required.”

Shamitabh was a story about how two characters—Amitabh Sinha (played by Bachchan) and Danish (played by Dhanush)—come together, somewhat reluctantly, to be the voice and face, respectively, of an actor. “I was on the way to Amitji’s house to wish him on his birthday, when I was wondering what to gift him,” recalls Balki. “That is when I thought of gifting him the idea of this film. It was based purely on his voice.”

The shooting of the film, too, was a unique process. “Dhanush had to act to someone else’s lines. Amitji had to dub thrice for the film: Once for himself, once for Dhanush—these were before the film was shot—and then again for himself post-production.” The film also had Bachchan sing the mellifluous ‘Piddly si baatein’, penned by Swanand Kirkire to the music of Illaiyaraaja. “Amitji loved the idea of Shamitabh, people loved the idea of the film, but somehow it did not do well,” says Balki. Was it because the audience could not associate Bachchan’s voice with someone else’s face? “It is difficult to say why it did not do well. Sometimes it just does not work,” he says.

Now that Bachchan’s career as a singer and voice artiste has come full circle again, is the next step another music album? “Yes, it is something that we have been interested in, and have talked about,” says Sagoo. “It would be good to get his son [Abhishek] into it as well, and get him to do a rap.”

First Published: Dec 27, 2019, 14:39

Subscribe Now