Meet the 'work from village' brigade, ditching cities for hometowns

Many white-collar workers are leaving crowded and costly cities to work from the comfort of their villages and hometowns in the wake of the pandemic

Vumonic Data Labs CEO Aravind Raju (extreme left) with his team at Raju’s grandmother’s house in Thevaram in Tamil Nadu where they moved to work through the pandemic lockdowns

Vumonic Data Labs CEO Aravind Raju (extreme left) with his team at Raju’s grandmother’s house in Thevaram in Tamil Nadu where they moved to work through the pandemic lockdowns

A few weeks ago, a BBC news channel journalist who was interviewing an expert on a video call was interrupted by the latter’s young daughter on live television. The video caught the eyes of more than eight million people on social media, and was shared by Scott Bryan, co-host of the Must Watch podcast, on his Twitter account. Parents around the globe are tackling the challenges of managing work with little ‘co-workers’ at home during the pandemic. Some of them, like Jayasankar Reddy Singam of Bengaluru, are taking work from home a step further by trying to balance childcare and work by moving away from the bustle of the city to a quieter life in the village.

Singam, a software developer with an international IT company in Bengaluru, relocated to Baisukuppam in the Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak, after being away for more than 10 years. Back in 2008 when he migrated to the city to pursue higher education, he was the first graduate from the hamlet that only has a population of about 400 people. Many others followed in his footsteps later.

Life seems to have come full circle as he has now returned to the home he grew up in, along with his wife and three-year-old son. “My parents are really happy to have us around. They used to dream about it and we’re glad to be back. Initially I faced some hurdles while adapting to work conditions here, but now everything is smooth, except for my son continuing to tease me on his bicycle while I work,” he says.

Apart from saving up to Rs 15,000 per month, Singam has managed to introduce the villagers to a healthier lifestyle. “I have initiated physical activities like playing volleyball, cricket and taking morning walks, instead of playing mobile games like PUBG, Free Fire etc. I also motivate villagers to harvest rain water and teach them about the importance of growing organic food,” says the 31-year-old. Along with office work, Singam now lends a helping hand in his father’s agriculture work and grows organic vegetables on their two-acre land.

Software developer Jayasankar Reddy Singam, who relocated from Bengaluru to his village in Chittoor district in Andhra Pradesh with his wife and three-year-old son, often works on the road near his home since the best signal is available there in Andhra Pradesh

Software developer Jayasankar Reddy Singam, who relocated from Bengaluru to his village in Chittoor district in Andhra Pradesh with his wife and three-year-old son, often works on the road near his home since the best signal is available there in Andhra Pradesh

After the government announced a nationwide lockdown in March-end, many migrant workers walked hundreds of kilometres to go back home. Many white-collar urban professionals too wanted to go back home, especially with rising number of cases in the metros and living in cramped houses under lockdown. Many preferred getting back to the villages for what they perceived as a better quality of life, without the monetary burden of high monthly rents, among other things.

Twenty-four-year-old Aishwarya Nair, a software engineer at L&T Infotech, relocated from Mumbai to Valakom in Kerala’s Muvattupuzha town in the first week of June. Remote working was supposed to be the new normal, but it had increased her work load and it was becoming difficult to maintain a work-life balance.

Back with her parents in the village, she faced initial hiccups, especially given her odd shift timings—from 2.30 pm to almost 1.30 am, of internet connectivity and power cut issues. Her parents took care of the latter by installing a solar inverter at home. Gradually Nair started enjoying working from the village. “In Mumbai, there is a rush in the vibe itself, here it is very peaceful. I have time to pause and embrace the moment. Finally, I’m detoxing my lungs with the fresh air,” says Nair.

Software engineer Aishwarya Nair is glad to be with her parents in Valakom in Kerala

Software engineer Aishwarya Nair is glad to be with her parents in Valakom in Kerala

In Valakom, she accompanies her mother to the river to wash clothes and also intends to learn to swim. “There is a jungle-like area near our house and I love climbing trees there. I’m so happy that I came here… now that there is no clear end to this WFH situation, I’m glad that I’m in my village with my parents rather than in Mumbai,” says Nair, who vacated her house in Mumbai since she is not sure when she would return, but thinks that she would come back to the city eventually.

Young and aspirational Indians often move from rural to urban areas for better economic opportunities. According to news reports, the number of migrants who moved from rural to urban areas in India, as per the 2001 Census, stood at 52 million out of a total population of 1.02 billion. In 2011 the number jumped to 78 million. The share of urban-to-rural migrants in the population rose from 5.06 percent to 6.5 percent during the same time period.

Sridhar Vembu, founder of business software solutions company Zoho, always thought that people migrating from villages to cities was not a good idea. In a previous interview he told Forbes India that there was a lot of talent in the villages and they could do wonders if given the right opportunity and platform. He is on a mission to find ways to unleash this hidden potential, for which he also moved to a village called Tenkasi in Chennai. Vembu plans to set up small rural offices where he will identify and nurture rural talent. He suggests that other business leaders should consider this as well since there is a lot of underexplored potential in the 600,000-odd villages in India.

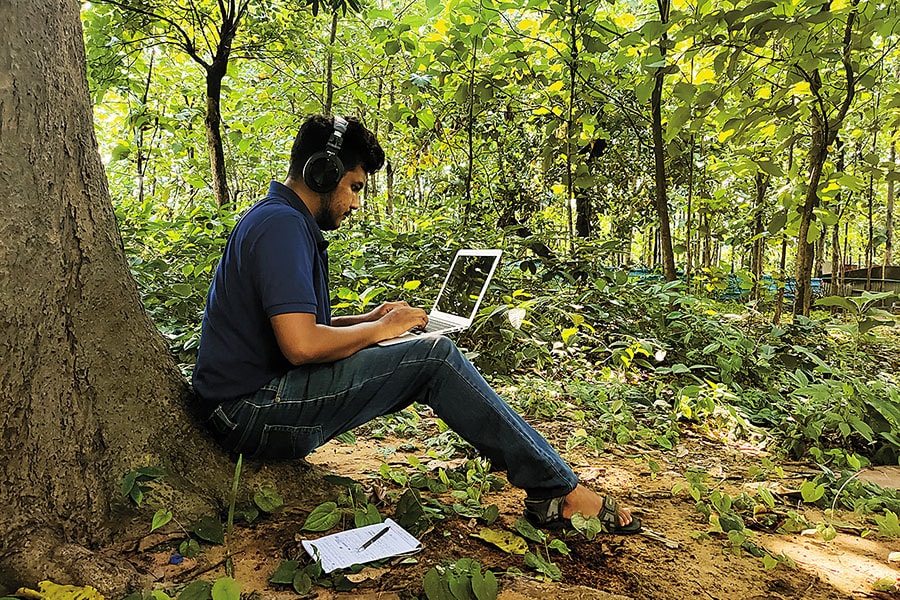

A startup in Bengaluru is walking the same path. The pandemic resulted in Aravind Raju, CEO and co-founder of Vumonic Data Labs, a data analytics firm, to execute his long pending plan to relocate business to his village. In March, when the employees were skeptical about coming to office, Raju offered to move operations to his grandmother’s farmhouse in Thevaram, a town in the Theni district of Tamil Nadu. The team of 12 agreed. Later, some people had to leave as their family wanted them to return home but six of them are still working from there. “There was a sudden change in our lifestyle. Being away from the hustle and bustle of the city, the team’s productivity multiplied. Also, there was no fear of contracting the virus. We successfully revamped our email cleaning app called InstaClean, which helped us get many new users,” says Raju. InstaClean, which had only one lakh users before the lockdown, now has more than 10 lakh users.

“We’re managing a proper work-life balance here. We follow a 7-8-9 rule… work for seven hours, sleep for eight hours and [keep] nine hours for other activities. We play different games every evening and explore nearby places on the weekends,” he adds. The two-year-old startup also recently hired six interns from the same village who are helping out with marketing. The senior team members are teaching English to some of them, as well as offering career guidance. One of the interns is building a web application for InstaClean. “My team is thoroughly enjoying this experience. The content writing and graphic designing team told me their creativity improves in peaceful and green surroundings,” says Raju.

Anish Choudhary, a public relations professional, found working remotely from Talcher in Odisha a nightmare initially but has now managed to figure out the logistics

Anish Choudhary, a public relations professional, found working remotely from Talcher in Odisha a nightmare initially but has now managed to figure out the logistics

The transition has not been as rosy and smooth for everyone. Public relations professional Anish Choudhary, who moved from Delhi to a village called Badajorada in Talcher, Odisha in March, describes the experience as a “roller-coaster ride and a nightmare” in the initial months. The lack of proper infrastructure and connectivity issues meant he was unable to cope with his prolonged working hours. “For the first three months, due to heavy rains, there used to be no power. During one of those months, there was a regular power cut between 6 and 10 am,” Choudhary explains.

“In fact, during the Amphan Cyclone, we were without electricity for four days straight. We had an inverter but it was not fruitful,” says the 23-year-old. At one point Choudhary was so exhausted he contemplated going back to Delhi. With time, however, he managed working from the village, his motivation being that he didn’t want to leave his parents alone during these uncertain times. “I’ve started going out and exploring my village. Working from village was a nightmare but is now a beautiful dream come true because, above all, there is mental peace here,” he says. Choudhary continues paying rent for his Delhi house since his belongings are still there and plans to go back once office resumes.

Some professionals who intend to return to cities once offices resume are also contemplating shifting to villages permanently in the near future. Like Kiran Varma, a technical architect with Absyz Sofware Consulting in Hyderabad, who moved to his village Buddam in the Guntur district in Andhra Pradesh. He considered it an opportunity to revisit his roots and enable his four-year-old son to have the same experiences he grew up with. “After the lockdown, I experienced working from home and now I’m getting the village experience as well, which is quite good. My lifestyle has changed and I plan to move here 10-15 years down the line,” says Varma.

While Covid-19 has resulted in more flexible and agile workplaces, “we will need a robust digital network, infrastructure, technology adoption, education and empowerment at the village level to sustain the ‘work from village’ model in the long term”, believes Harshvendra Soin, global chief people officer and head of marketing at Tech Mahindra. According to him, it’s time to utilise the country’s talent pool to the fullest by creating ‘Smart Villages’ in tandem with ‘Smart Cities’.

Soin strongly believes the future of work in the post-pandemic world will be a combination of physical and virtual, and this hybrid model will allow people to work from anywhere—even from remote village locations. “This will allow people the freedom and flexibility to set their own rules, based on their personal or professional commitment, and productivity levels. In all this, technology and connectivity is going to play the role of a key enabler.”

****

New lease of life

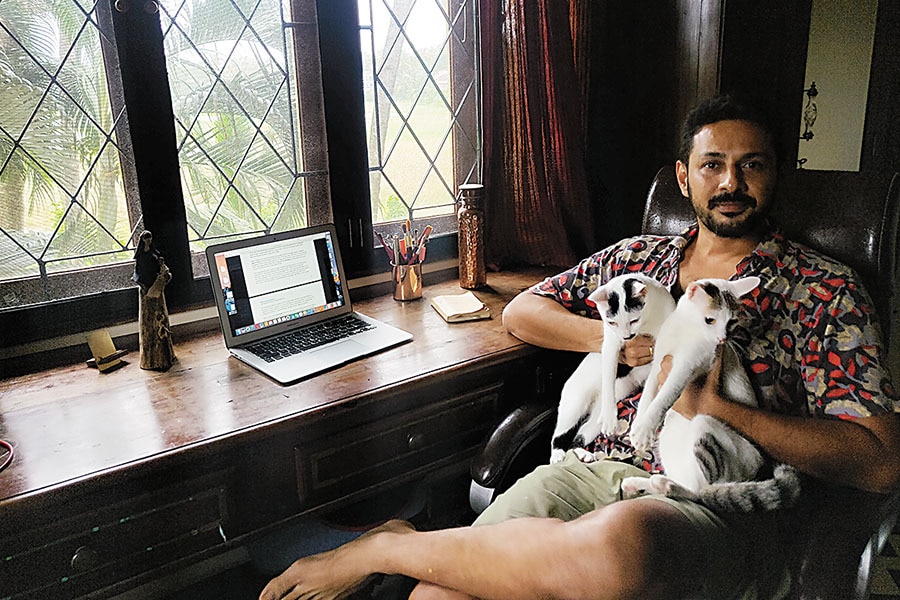

In 2018, National Award-winning editor and screenwriter Apurva Asrani was diagnosed with Bell’s Palsy, a type of facial paralysis that results in an inability to control the muscles on the affected side. He couldn’t shut one of his eyes for three months and had to tape it shut. While the treatment was going on, Asrani flew to Goa to celebrate his 40th birthday which turned out to be an extended trip as he was feeling quite relaxed there. He consulted doctors in Goa and started recovering faster.

By the time he recovered fully, Asrani had already made up his mind to leave Mumbai and permanently shift to Goa with his partner. “I went into a huge shock when I woke up with half my face paralysed in Mumbai. The reason it happened was because I was extremely overworked and stressed out. I was working in three shifts—day and night, without taking proper rest. When I was diagnosed with Bell’s Palsy, it was a very tough phase. There was a point when doctors were trying their level best but my face was just not showing any positive sign of getting back to normal,” says Asrani, who has written Manoj Bajpayee-starrer Aligarh.

After moving to a village in Goa, Asrani realised that he didn’t need more work because of his low-maintenance lifestyle. “I don’t have to go to parties, there’s no pressure to buy the coolest new car or shop at Zara or any other expensive brands. Everyone is far more relaxed about these things here. So I realised I didn’t have to be doing three films simultaneously,” he says. Asrani doesn’t plan to move back to the city. He has found his happy place.

On a workation

Work from Mountains (WFM) is an initiative between Sunshine Adventures and Travel The Himalayas, and is led by Panki Sood and Prashant Mathawan. The founders wanted to help people get away after being cooped up indoors due to the pandemic, and decided to provide them a chance to work from beautiful mountain regions. “When we launched this initiative in July, people were really interested in moving to the mountains. Thousands of people have enquired and 20 bookings are already in,” says Mathawan.

So far, they have eight properties across Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh and will keeping adding more as the demand goes up. One of the guests drove all the way from Hyderabad to Uttarakhand and is working from the mountains now. “Not all the properties have wifi or broadband, though 4G coverage is good everywhere,” he adds. Their monthly charges start from `35,000 per room for two people and one can stay here up to seven months. “Our travel and hospitality businesses were terribly affected and these properties were also lying vacant, so we thought of introducing this initiative to cope with the crisis. Thinking differently is the only way forward,” says Mathawan.

First Published: Aug 20, 2020, 15:06

Subscribe Now