Nine years ago, a Chennai-headquartered software products firm purchased 4 acres of land in one of the villages, Mathalamparai, to begin operations from the district— roughly 650 km from the Tamil Nadu capital.

Its founder, born in a village in Tamil Nadu’s Thanjavur district into a family of farmers who later went on to study at Princeton University, New Jersey, work at Qualcomm in San Diego, California, and later live in and around the San Francisco Bay Area, had a vision: To take Silicon Valley to the village.

Meet Sridhar Vembu who, in his late 20s, founded AdventNet in 1996 to make software products at a time when IT services were the rage. In 2009 he renamed the company Zoho Corp to reflect the transition from a software company serving network equipment vendors to an innovative online applications provider.

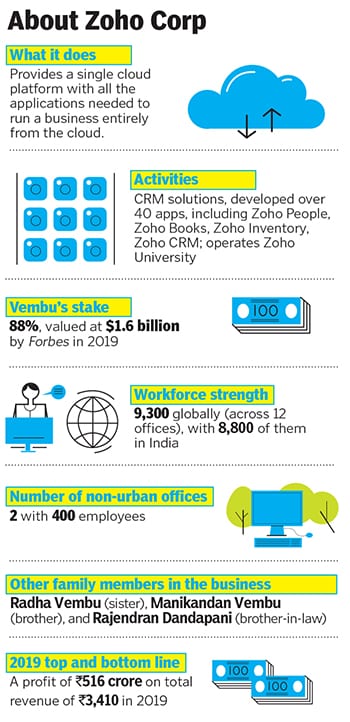

Zoho today provides cloud-based customer relationship management (CRM) solutions and over 40 apps for, among other activities, online accounting, human resource and inventory management. A few of those products, including Zoho Desk, a customer service software, were built out of the Mathalamparai office, vindicating Vembu’s vision that you didn’t have to be in the urban hubs to develop world-class products.

Before moving to Tenkasi, Vembu lived in and around the Bay Area in San Jose and Pleasanton. Until October 2019—months before the Covid-19 pandemic erupted—when he made the big move to the small town. Today, in a Covid-19 world, work from home is a mantra. For 53-year-old Vembu, work from village has been a mission for some time now.

“I always thought that people migrating from villages to cities is not a good idea,” Vembu told Forbes India in a relaxed conversation over Zoho Meeting on a mid-May morning from his Tenkasi home. “About a year or two ago, I decided that I want to do something new. I want to go to the smaller villages and set up what I call satellite connected office centres where 10 to 20 people will work.”

As of now, Zoho has two rural offices, one in Tenkasi and the other in Renigunta in Andhra Pradesh with 500 of its 9,300 employees globally working out of these the plan is to have many more of its 8,800 India-based employees working out of non-urban India.

His motivations to go rural are two-fold: “One, I want my employees to live in these villages because it brings a lot of cross-fertilisation of ideas. Once some high-earning people come in, they bring in good and bad habits.” The good stuff, like mentoring and coaching, is what Vembu hopes the city folk can lend to the local youth, who Zoho can then recruit. “So it would be a two-way exchange here... It was a new challenge, but then I decided that if I’m going to start these rural initiatives, I’m going to need to set myself up in the village, too.”

Over the past eight months, Vembu has swimmingly moved back to his rural and agrarian roots. A typical day begins at 4 am when he does calls to the US offices. By 6 am, he’s off for a long walk and, on occasion, a swim in the village well. Snake-spotting, and a few times even catching them, is one activity during the stroll.

He returns for breakfast, after which he takes stock of engineering projects, reviews codes and takes customer calls. Then it’s time to indulge in a bit of what his ancestors did for sustenance.

Vembu steps out to the fields to grow paddy, vegetables like tomato, brinjal and okra, and fruits such as mango, watermelon and coconut. Life in Tenkasi opened up new horizons even as the hubs of commerce stayed locked down.

![zoho zoho]()

“I feel more connected to my roots and enjoy this kind of life where you get rid of your comparisons. You don’t have to worry about things like: Does my neighbour have a Ferrari or does my neighbour take a vacation? You kind of reduce it to a more elemental simplicity in life. I’ve always been a low consumption person. When any new phone is launched in the market, I won’t be the first in line to buy it I may buy it after a couple of years after everybody has it,” he says with his trademark guffaw.

In 1989, Vembu graduated out of IIT Madras, following up with a PhD in Princeton and then a job as a wireless systems engineer at Qualcomm for two years. In 1996, along with two of his brothers (he has three of them) and three friends, he co-founded AdventNet.

“When we decided to launch this company, one thing that I noted was in India we have perfect talent but we produce almost zero software products. So that was clearly an opportunity, obviously it was going to come with a lot of problems but we were prepared to face them. I always felt that in order to advance economically, you needed to take up these complex tasks. I come from a rural background but I also knew that you ought to do complicated things,” he laughs.

Zoho has earned the distinction of being the first software product unicorn, and Forbes in 2019 valued Vembu’s 88 percent stake at $1.83 billion. In 2019, Zoho reported profits of ₹516 crore on total revenue of ₹3,410 crore. The company claims to have 50 million users globally for its apps, the latest of which was launched in the wake of the pandemic and is suitably called Zoho Remotely.

As India endures a reverse migration of millions, Vembu’s blueprint for a world in which folk get educated in the village and stay back to work there takes on huge meaning.

![shailesh kumar davey shailesh kumar davey]()

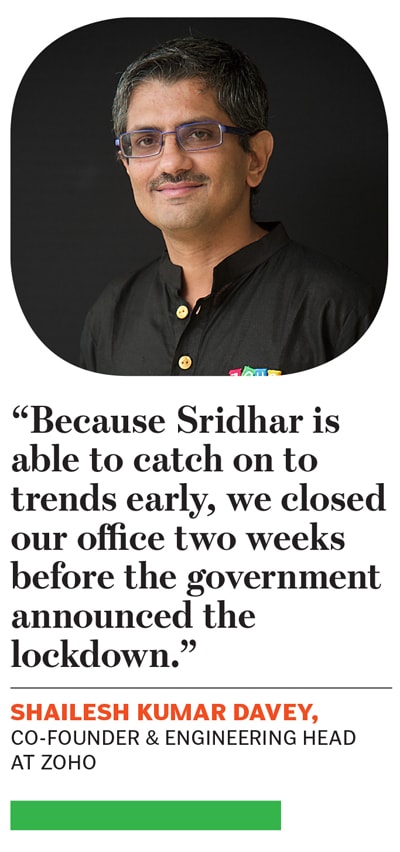

“Sridhar is able to catch such trends very early and so he would then start convincing people about those things. We all joke internally that the trend may be right but we don’t know when it will be in effect. He would argue that by the time the trend comes, we all will be dead. That would be our banter,” grins Shailesh Kumar Davey, co-founder and engineering head at Zoho.

“But because he is able to latch on to trends early, we closed our office two weeks before the government announced [a lockdown]. He wanted employees to reach their hometowns before trains, buses and airports become crowded with sudden panic.”

Even as Vembu’s idea of cross-fertilisation begins to play out, he’s also embarked on a mission to build an army of engineers—not those with conventional degrees but those trained in-house.

In 2004, the founders started Zoho University, now known as Zoho Schools, to onboard and train students with skillsets and abilities. Students are not charged a fee but are paid a stipend of ₹10,000 throughout the tenure of the two-year course.

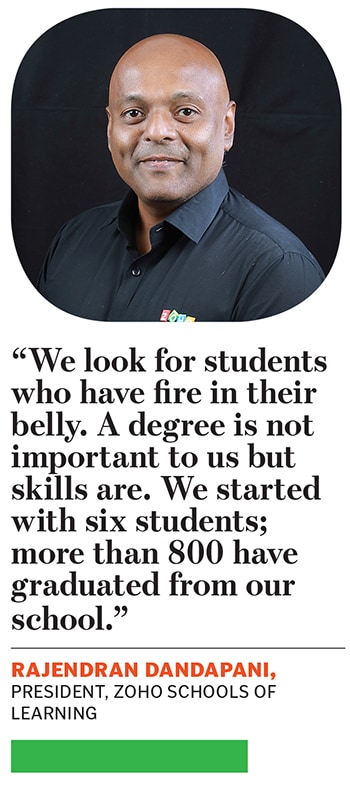

“We look for students who have fire in their belly. A degree is not important to us but skills are. We started with six students and two professors and today more than 800 students have graduated from our school and most of them are employed with Zoho Corp,” explains Rajendran Dandapani, director of technology, Zoho Corp, who is also Zoho Schools of Learning’s president.

Dandapani’s son studied in the same school and later became a productive employee in the company. “90 percent of our students are from Tamil Nadu. The institute itself is housed within Zoho’s offices in Chennai and in Tenkasi, so students engage with the employees and experience the office culture. By the age of 21 these students are already employed and earning while other students of similar age will still be studying,” he adds. Most students hail from small towns who only have a dream to become an engineer.

Out of 9,300 employees, 875 are students from Zoho Schools. This also includes Abdul Alim who was employed as a security guard at Zoho and is now a programmer. “A Zoho employee spotted him working on his computer at the reception desk and found that he had passion for programming. Alim then joined Zoho Schools, graduated from it after the 18-month programme. He now works as a programmer in the Zoho Charts team,” says Vembu.

![mohandas pai mohandas pai]() Saran Babu Paramasivam, a Zoho Schools product, shares his experience of how he couldn’t even operate a computer back in 2005 but now works as a senior product manager at Zoho. “I don’t have a degree and you know how difficult it gets when you have to go through an arranged marriage. But I explained to my wife’s family about what I do and they were convinced. It was good to see how society is changing and a degree is not important anymore. All my dreams are fulfilled—I have my own house and car, I have travelled to most of the countries,” says Saran who has been associated with Zoho for 15 years now and, along the way, also encouraged his younger brother to join Zoho Schools he, too, now has a job with Zoho Corp.

Saran Babu Paramasivam, a Zoho Schools product, shares his experience of how he couldn’t even operate a computer back in 2005 but now works as a senior product manager at Zoho. “I don’t have a degree and you know how difficult it gets when you have to go through an arranged marriage. But I explained to my wife’s family about what I do and they were convinced. It was good to see how society is changing and a degree is not important anymore. All my dreams are fulfilled—I have my own house and car, I have travelled to most of the countries,” says Saran who has been associated with Zoho for 15 years now and, along the way, also encouraged his younger brother to join Zoho Schools he, too, now has a job with Zoho Corp.

“15 to 20 percent of our engineers do not have an engineering degree. They are all trained in-house. Zoho Schools allows you to bypass colleges, and we’re trying to go all-digital now,” says Vembu.

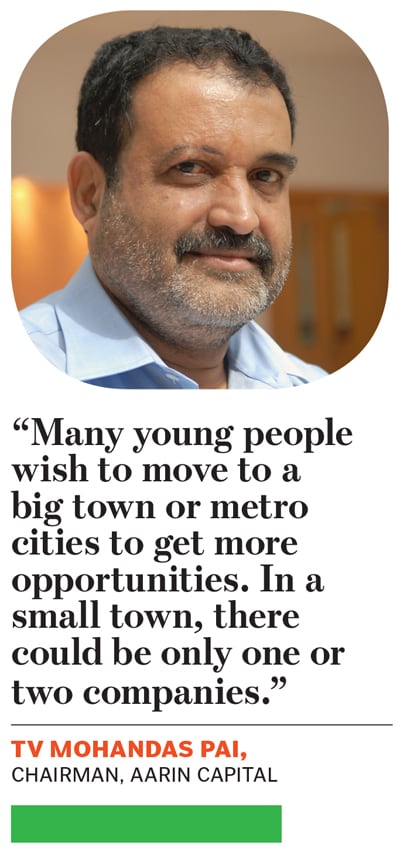

Not everybody believes migration to urban commercial hubs can be curbed by generating more jobs in rural areas. According to IT sector veteran TV Mohandas Pai, now chairman of Aarin Capital, creating more job opportunities in rural areas is not viable due to certain constraints. “Many young people wish to move to a big town or metro cities to get more opportunities. In a small town, there could be only one or two companies, there will not be 100 companies. So you’re stuck with the same company who pays you a certain amount of salary and compensation. In a big town, you can always change jobs, go to the highest bidder, make more money, and switch to three or four jobs in five years.”

Pai instead believes India should invest in greater urbanisation. Small-town education may work in the US because they have a lot of universities there. It may even work in India in a place like Manipal, in the city of Udupi in Karnataka.

“It [Manipal] has 30,000 people and a university from which young people graduate. Also, people in the south are highly educated, so it can work there. But if you want to do it in Kalahandi [in Orissa] then it will not work,” adds Pai.![rajendran dandapani rajendran dandapani]()

For his part, Vembu’s alternative to conventional education—“our kids become good testers, but are not necessarily well-educated,” he quips—ties in with a hope to build capabilities within India. And that, in turn, ties in with the government’s recent pitch of self-reliance and ‘vocal about local’. A few days before that, Zoho had launched a Swadeshi Sankalp initiative for the education and government sectors, offering them a slew of apps to connect students, to build a Covid-19 call centre and for health surveys.

Swadeshi (made in India with Indian material) is important to Vembu, but he also recognises the need for global trade—“but with balance”. And he’s no fan of making India a factory for the world.

“Actually nobody should be the factory of the world. There is a lot of imbalance and we are getting indebted in order to buy… We have to develop an economic structure that values balance.” (For more on this read the interview with Vembu that follows this feature.)

Building capabilities is Vembu’s idea of wealth creation, not financial valuation. “I am a capitalist and I don’t care about net worth.” He gives the example of Japan to explain (in pre Covid-19 times, of course). “When you go to rural Japan, you can see a wealthy society. Roads are good, infrastructure is great and you don’t see any homeless people, you don’t see any poverty. On the train station, the trains run on time. The trains are clean, high speed trains, all of that. That is wealth. Clearly Japan is wealthy. And to me, wealth actually also connotes resilience. Capital is something that protects you from adversity.”

At dusk, Vembu sets out for another walk in the village, and ruminates: For instance, he observes that farm animals like cows and chicken roam around all day, but they come back at a fixed time—they know what is home. He likes taking long walks and swimming, as these activities allow him the mental space to think. Vembu doesn’t watch TV, but sometimes listens to music. He retires to bed by 8 pm, spending some time reading or online (on Twitter).

Ask him whether he sees a more active role for himself in governance and policy-making, and he’s clear that “people with ideas should enter politics. I never considered politics to be dirty because the alternative to politics is war. If we don’t have politics then we will have war.” But he’s in no hurry to take the plunge. Maybe in 10-15 years.

“I have much more to build. So not right now. But like, as my mother said, first let’s survive the virus.”

Vembu in front of his office in Mathalamparai village of Tenkasi

Vembu in front of his office in Mathalamparai village of Tenkasi

Saran Babu Paramasivam, a Zoho Schools product, shares his experience of how he couldn’t even operate a computer back in 2005 but now works as a senior product manager at Zoho. “I don’t have a degree and you know how difficult it gets when you have to go through an arranged marriage. But I explained to my wife’s family about what I do and they were convinced. It was good to see how society is changing and a degree is not important anymore. All my dreams are fulfilled—I have my own house and car, I have travelled to most of the countries,” says Saran who has been associated with Zoho for 15 years now and, along the way, also encouraged his younger brother to join Zoho Schools he, too, now has a job with Zoho Corp.

Saran Babu Paramasivam, a Zoho Schools product, shares his experience of how he couldn’t even operate a computer back in 2005 but now works as a senior product manager at Zoho. “I don’t have a degree and you know how difficult it gets when you have to go through an arranged marriage. But I explained to my wife’s family about what I do and they were convinced. It was good to see how society is changing and a degree is not important anymore. All my dreams are fulfilled—I have my own house and car, I have travelled to most of the countries,” says Saran who has been associated with Zoho for 15 years now and, along the way, also encouraged his younger brother to join Zoho Schools he, too, now has a job with Zoho Corp.