How India's restaurants are staying alive

With no government stimulus yet, F&B players are struggling to find viable revenue streams through food delivery, new product lines, online classes and even supplying essentials—from staples to condom

Gourmet restaurant Tres in Delhi has started doing food deliveries with an edited menu that does away with a lot of the fluff[br]It’ll be remembered as a sign of our times that René Redzepi’s two-Michelin-star Noma in Copenhagen—widely known as the ‘world’s best restaurant’, famed as much for its signature ‘Hen and the Egg’ dish as its year-long waitlist for reservations—is now reopened for the coronavirus age… as a burger joint.

Gourmet restaurant Tres in Delhi has started doing food deliveries with an edited menu that does away with a lot of the fluff[br]It’ll be remembered as a sign of our times that René Redzepi’s two-Michelin-star Noma in Copenhagen—widely known as the ‘world’s best restaurant’, famed as much for its signature ‘Hen and the Egg’ dish as its year-long waitlist for reservations—is now reopened for the coronavirus age… as a burger joint.

Instead of dishing up elaborately cooked game and delicately plated fronds and forest berries, Redzepi has perhaps pioneered another era for restaurants around the world, as they struggle with the fallout of Covid-19 lockdowns. Noma’s current avatar features a casual garden wine bar, and a takeout menu with two items only—a cheeseburger and a vegetarian burger. Guests are welcome to ‘come as you are, there are no reservations’, and the burgers cost about $18, a far cry from the almost $400 a Noma meal would typically set you back by.

The transformation isn’t permanent, of course, but a stand-in measure until Noma can prepare for a full reopening. On its website, Noma says this is the first phase of reopening, focussed on connecting with their community.

Closer home, too, restaurants find themselves innovating to survive in similar circumstances. In a first for the five-star chain, Marriott hotels across the country are now delivering meals via Swiggy and Zomato, while Delhi’s fine-dine restaurant Tres—shut for almost two months—started an edited delivery menu that did away with a lot of the fluff. Instead of gels and flambé, Tres is now serving café-style comfort food, with a gourmet element.

“We asked ourselves, who are we as professionals?” says Jatin Mallick, co-founder of Tres. “Yes, we do gourmet food, but is that all? Right now, it’s not about making money, because there isn’t much of that to be done either way. But we can bring happiness to people not just through an elevated plate of salmon—we can do it with a wholesome arabiatta pasta too.”

The food and beverage (F&B) industry, India’s largest employer after agriculture, responsible for more than 7.3 million livelihoods, has been among the worst hit by the coronavirus. An industry that works on razor-thin margins, even under normal circumstances, still has to pay high rents, utilities and other fixed costs, along with employee salaries. With negligible cash flows coming in, many F&B companies have furloughed staff others have rationalised with pay cuts or have had to let go of employees.

In a blogpost detailing that Zomato would have to lay off 13 percent of its staff, founder Deepinder Goyal estimated that 25-40 percent of Indian restaurants will close in the coming months. An alarming statement by the Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Association of India released in May said that as many as 70 percent of hotels and restaurants will have to shut shop without government intervention. Restaurants like Smokehouse Deli started delivering DIY kits for families to cook during

Restaurants like Smokehouse Deli started delivering DIY kits for families to cook during

the lockdownOne of the first reported casualties is pastry chef Pooja Dhingra’s casual dining space in Mumbai’s Colaba, Le 15 Café, which announced that it would shutter in May. “To run a space like ours in Colaba, my main concern was a lack of customer walk-ins—a large portion of our revenue comes from the tourist segment,” she says. “Considering that and the onset of the monsoon, I didn’t think we would be able to pay high rents without enough customers, and we’d also face losses from following the social distancing norms once we reopen.”

Since the beginning of the lockdown, restauranteurs, foreseeing disaster in the industry, have been lobbying for government stimulus. After two months of silence, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman held a virtual meeting with a four-member team of restauranteurs on May 21, which lasted 30 minutes. The team put forward its requests, from liquidity support to policy support, but at the time of going to press, no relief had been extended.

“Going ahead, it’s an existential crisis,” says Anurag Katriar, president of the National Restaurants Association of India (NRAI), and executive director & CEO, deGustibus Hospitality. “Many, in the absence of any aid, will not be able to resurface after the lockdown is over. This will even impact bigger players—they might not shut down shop completely, but if a portfolio has 20 restaurants, they may shut about 30 percent. We will have to recalibrate all our expenses.” QSR chain Wow! Momo has diversified into delivery of essentials, from staples to sanitary

QSR chain Wow! Momo has diversified into delivery of essentials, from staples to sanitary

napkins and condoms, to tide over its first losses in 11 yearsWhile states have allowed restaurants to operate home delivery, volumes are so negligible that there is little business sense in operation. For most, it’s a temporary measure to keep employment going and connect with customers.

It is actually more expensive to carry out delivery than to run a restaurant set-up, adds Amlani, explaining that these restaurants were not set up for home delivery, so neither are their costs. “Your delivery density is lower, making it less sufficient. You are still paying expenses for little income. At Impresario, we are making the staff stay on the premises, so those costs go up too,” he adds.

The MHA has mandated the opening of restaurants from June 8, but Amlani isn’t sure if the social distancing norms will give dine-in the impetus it needs. “If restaurants are to open back up at 50 percent occupancy, we will bleed money,” he says. “Then we’re better off closed. We need to follow social distancing norms and operate at least at 66 percent capacity to be able to even pay salaries.”

“Our biggest worry remains our employees,” agrees Katriar. “So far, we are holding on, making sure no one goes hungry. But in the absence of any economic package from the government, this status may change over the next few weeks. With no source of income, there are only two ways to survive: Dip into cash reserves, which only a handful of companies have, or through equity and debt financing, neither of which is easy under the circumstances. Our abilities and resources are slowly drying up.”

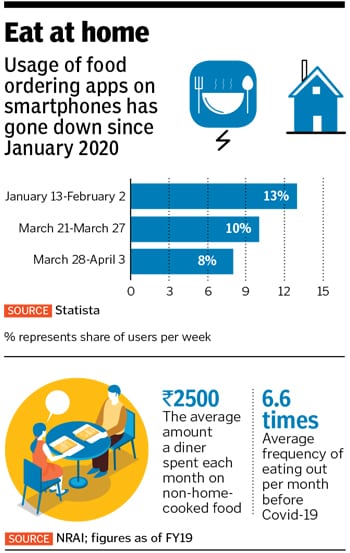

As per FY19 figures from an NRAI report, an average 44 percent of consumers would eat non-home-cooked food two-three times a month, and 19 percent would do so two-three times a week. With all dine-out revenues demolished, and customers wary of ordering in too, this number is probably down to a small percentage ordering food once a month, or once in two weeks for the more adventurous, taking anecdotal evidence.

Customer confidence, already low even though the myth that the coronavirus can transmit through food has been debunked, faces further hits every time someone at a restaurant or at a delivery chain tests positive for Covid-19.

“When a pizza delivery boy tested positive in Delhi in early April, it was blown out of proportion, and we saw sales fall instantly,” says Sagar Daryani, co-founder of quick-service restaurant chain Wow! Momo. “We haven’t recovered from that yet. But we need to deal with such cases with a lot of compassion, supporting each other and our people, rather than point fingers. We need to educate consumers to do so too, because there are millions of deliveries happening, and our employees are also human.”

Mumbai-based Hunger Inc, which runs The Bombay Canteen and O Pedro, had to shut their delivery kitchens after a staffer tested positive in the middle of May. They immediately put out a post with the information on social media, and contacted guests who had ordered from them to let them know. “I’ve personally spoken to a lot of guests who ordered from us in the past few weeks, especially in the light of the incident, and fortunately, most people understand that we now live in an era where this can happen anywhere,” says Sameer Seth, co-founder. “You can step out for groceries, or even to take the trash down, and you can expose yourself. Simple acts are no longer taken for granted. What is required is to have an open conversation about it. You feel fear when you don"t understand what"s going on.”

In survival mode

With little clarity on when restaurants will open up again—and whether they will see takers when they do—F&B players are finding themselves forced to innovate and explore alternative revenue streams, albeit most of them are not expected to contribute significantly in offsetting losses. Chef Hussain Shahzad of Mumbai restaurant O Pedro hosts poee-making workshops onlineMany of them who never intended to get into the delivery business now find that that’s the only viable option for the short term. “I’ve been one of the biggest proponents against delivery, since our restaurants are all about experiential dining,” Zorawar Kalra, founder and MD, Massive Restaurants, said at a recent Retailers Association of India webinar. “But I think delivery as a percentage of your overall revenue will gain a lot more prominence, even for a company like mine. I always thought our food would not be easy to deliver, but we will have to innovate. Will it be able to cover up losses in dining sales, though? Obviously not.”

Chef Hussain Shahzad of Mumbai restaurant O Pedro hosts poee-making workshops onlineMany of them who never intended to get into the delivery business now find that that’s the only viable option for the short term. “I’ve been one of the biggest proponents against delivery, since our restaurants are all about experiential dining,” Zorawar Kalra, founder and MD, Massive Restaurants, said at a recent Retailers Association of India webinar. “But I think delivery as a percentage of your overall revenue will gain a lot more prominence, even for a company like mine. I always thought our food would not be easy to deliver, but we will have to innovate. Will it be able to cover up losses in dining sales, though? Obviously not.”

If diners earlier counted price as the most prominent factor in choosing where to order from, it will now be second (or third) to trust and hygiene. Premium restaurants that guests have physically dined at, and seen the hygiene levels of, will stand a better chance at earning this trust than cloud kitchens.

“We really need to be nimble-footed and create a revenue stream for our restaurants,” says Khushnooma Kapadia, area director of marketing, South Asia, Marriott International, about the Marriott on Wheels home dining initiative. “While we know we cannot give you the full experience of dining at our restaurants at home, the food can definitely be delivered. We’ve seen a lot of people asking for deliveries, especially to celebrate special occasions such as Eid and Mother’s Day.”

Chef Prateek Sadhu of Mumbai-based progressive restaurant Masque, who started off the year with an experimental space called the ‘Masque Lab’, says he is looking at offering the Masque experience in different formats, along with delivery. In the early days of resuming operations about a month ago, when the delivery and supply chains were still chaotic, Sadhu would hit the vegetable market in the morning, return to the restaurant to cook and then hop into his car to deliver the orders. Now that those systems have fallen in place, he"s considering branching out into multiple formats to support the people dependent on his business. “Besides the restaurant, I might start a line of Masque signature sauces. I am in talks to make apple cider with Masque branding, and with whatever cider isn’t sold, we can make vinegar in the lab. I"m trying to think of expanding in a way in which all my staff has a role to play,” says Sadhu.

Hunger Inc, similarly, catered to a Zoom wedding a few weeks ago, delivering biryani to 25 locations across the city. While their kitchens remain closed, patrons can still enrol for experiences through a tie-up with ticketing platform Insider.in, redeemable online or at a future date once restaurants restart. So for ₹500, you could purchase The Bombay Canteen’s cocktail and bar snacks recipe book and for ₹25,000 (for four people), take a private online cooking class with their popular head chefs, The Bombay Canteen’s Thomas Zacharias (learning dishes from his travels across India’s hinterlands) and Hussain Shahzad (Goan and Portuguese delicacies a la O Pedro).

“We"ve started a series of workshops and classes, where we’d send ingredients to you and teach you over Zoom. You are going to see a lot of experimentation, the core of which would be engagement through classes, and other sessions that we once used to do at the restaurant,” says Seth. Mumbai-based fine-dining restaurant Masque, led by co-owner and executive chef Prateek Sadhu, started deliveries to stay afloat through the lockdown[br]Sagar Daryani’s Wow! Momo went in an entirely different direction, and found that it is paying off. “We have 345 outlets, of which only 83 are operational for delivery as of May 27. Three days ago, we only had 67. In a normal, pre-Covid era, 25-27 percent of our business was delivery now, it’s 100 percent,” Daryani tells Forbes India. Desperate measures for times when his company recorded losses for the first time in 11 years, amounting to as much as ₹7 crore just for April.

Mumbai-based fine-dining restaurant Masque, led by co-owner and executive chef Prateek Sadhu, started deliveries to stay afloat through the lockdown[br]Sagar Daryani’s Wow! Momo went in an entirely different direction, and found that it is paying off. “We have 345 outlets, of which only 83 are operational for delivery as of May 27. Three days ago, we only had 67. In a normal, pre-Covid era, 25-27 percent of our business was delivery now, it’s 100 percent,” Daryani tells Forbes India. Desperate measures for times when his company recorded losses for the first time in 11 years, amounting to as much as ₹7 crore just for April.

“We are trying to be responsible and not have any job cuts. We are doing organisation-wide pay cuts of 30 percent, but as a young organisation that has cash reserves, has investors, what we do today will determine the preamble of the company going forward. We need to understand how to utilise our resources better. So, we have got into a new business line, called Wow Momo Essentials (WME),” he adds.

WME home delivers groceries and essential supplies via Swiggy and Zomato, within 45 minutes, using the same protocols as they do for food. “This way, more of our 2,700 employees are engaged. We can deliver eggs, bread, atta, vegetables, sanitary pads, condoms, everything in real time,” he adds. WME is now contributing 50 percent to the company’s topline if they did ₹2 crore in April, they will clock ₹5 crore in May.

The road ahead will see a lot more such innovation, along with consolidation and collaboration within the industry. Wow! Momo, for example, is partnering with Café Coffee Day to share space across outlets. “Young businesses like ours have to be agile. You will see a lot of mergers and acquisitions happening, so we can together convert the adversity into a challenge,” he adds.

Solving the last-mile problem

The restaurant industry was already struggling even before Covid-19, facing, among other challenges, high commissions (of around 20 percent of the ticket size) and deep discounting from aggregators such as Zomato, costs that they would have to foot.

Even after a few rounds of discussion, no concrete consensus has been reached with the aggregators, who now stand to gain more power in the realm of delivery. “Aggregators are in their own bubble right now,” says Amlani. “We’ve asked them many times to reduce commissions, but they claim their costs have also gone up so that’s a zero-sum game right now.”

While queries to Swiggy went unanswered, Zomato’s co-founder and COO, Gaurav Gupta, told Forbes India via email: “During a pandemic, aggregators like us play a significant role in making sure everyone has access to essentials like food and groceries without stepping out of their homes. Additionally, we play a key role in collaborating with restaurants to implement safety and hygiene measures. We also educate users of the measures that the restaurants are taking, so they can make an educated choice. This is critical to build user confidence and drive demand.”

Zomato has rolled out a ‘contactless dining’ feature (and claims to have signed up more than 25,000 restaurants for it) to use once restaurants can start up again, an end-to-end solution that starts from letting users identify a restaurant to go to, to contactless ordering and payment on the app.

“The preliminary response has been encouraging—restaurants are liking the product and believe that this will play an important role in the dining experience in current times. When users decide to dine out, they will see the safety and hygiene features offered by the restaurant, as these will be the key criteria for their selection,” he adds.

Even as the aggregator-restaurant dynamics remain a work in progress, new players are coming up in this space, spurred by the pandemic. The NRAI has already partnered with a company called DotPe (founded by former PayU executives), and another firm called BroEat has signed up 2,500 restaurants across India for its product.

Both DotPe and BroEat say their aim is to empower brick-and-mortar restaurants both are app-less platforms. DotPe, which commenced operations in October 2019, is a dining out and delivery solution—you can scan a restaurant’s QR code and a digital menu pops up, synced with merchant inventories. After the customer places the order and makes the payment online, all communication about food status and so on happens over WhatsApp from the restaurant’s own business account.

“We work with a small transaction fee for every successful transaction. It’s definitely an amount a merchant is comfortable with,” says Anurag Gupta, co-founder, DotPe, which also claims to have signed on 2,500 restaurants. “We are not a foodtech company. We are a B2B company, focussed on the merchants, and consumers via merchants—what we call B2B2C. Our positioning is different from Zomato, and our focus then is always on the merchants. I’m sure large players are eyeing this space, so we think we have come at a good time.”

BroEat is set up by Karan Tanna, founder of restaurant franchising company Yellow Tie Hospitality and cloud kitchen firm Ghost Kitchens, along with Pawan Shahri, owner of hospitality communications firm Chrome India and restaurants such as London Taxi. The venture is funded by the two, but not currently intended as a full-time business to compete with Swiggy or Zomato. “What we’re solving specifically is the unbundling of services—Swiggy and Zomato currently enable on-boarding restaurants, menus, order taking and delivery. Because they provide a bundled service, they can charge whatever commission they want,” says Tanna. “We are a community platform and are transparent with customer data as well as algorithms for display and visibility.”

While DotPe is offering solutions to individual restaurants, BroEat is a platform aggregator, as Swiggy or Zomato would be. Consumers interact with the platform entirely through WhatsApp. When you scan a QR code, a WhatsApp bot will send you a link to a landing page that displays all partner restaurants, where you can filter and make your selection, as you would on any other food delivery app. Like DotPe, you pay online and confirm your order, and receive invoice and tracking details on WhatsApp. The key is that restaurants, instead of being reliant on the aggregator for last-mile delivery, can select from a clutch of third-party players such as Dunzo, ShadowFax, WeFast and so on, which will be integrated into the platform.

“Until August 30, we won’t take any commissions after that, we will take ₹5 per order until ₹300 ₹10 per order from ₹300 to ₹1,000 and ₹20 per order for orders above ₹1,000. We are not partners, we are service providers. The restaurants should earn more,” says Tanna. BroEat is currently in the on-boarding phase, and aims to open up for use for delivery by the middle of June, in five cities to begin with.

Says Amlani. “The question is, what does an aggregator really do? It makes it easier to order food, and cover last-mile logistics. For this, charging an unfairly high premium means no one is making money—not even the aggregators themselves, it seems. Something’s got to give. There’s lots of last-mile delivery companies out there now, and integration will start pushing restaurants onto their own platforms rather than Swiggy and Zomato. It’s ironic that a crisis tailor-made for the benefit of aggregators is actually leading to their undoing.”

First Published: Jun 03, 2020, 13:05

Subscribe Now