Indian dating apps are swiping right on small towns

Made in India dating apps are getting it right in smaller cities by enabling youngsters navigate social dynamics, while US-based apps stumble

This September, 29-year-old Shweta from Bareilly in Uttar Pradesh was nudged by her friend to try out QuackQuack, a dating app. In her first tryst with online dating, she found quite a few young men in her town, with who she struck up virtual conversations. Then, about a month ago, she found a great match, and she has been dating the young man since. “We are actually considering a future together,” says Shweta, who was on the lookout for a serious relationship right from the beginning.

But although she has succeeded in finding a match, other hurdles remain. Shweta’s father is a government employee, and “I know half of Bareilly, and the entire city knows me,” she says. This means, meeting up with her date without being spotted by any of her friends or relatives is a tricky task. Consequently, they have not met up as often as they would have liked to.

Meeting up with his dates is also a concern for 28-year-old Hemant, a resident from Mau in UP. Not having found suitable matches on Bumble, the young man moved to QuackQuack, where he matched with a young woman in Varanasi, about 100 km away, and went all the way to meet her. In the four years that he has been on the app—many of his friends are too—he has dated women in and around Mau as well. But this has meant travelling several kilometres to an eatery outside the city, where the pair—especially the woman—would not be spotted by someone they know. Varanasi has proved to be more convenient, since it is a bigger city and he is an outsider there.

“QuackQuack has a lot of users from small towns with whom I can match. It wasn’t the case when I was using Bumble,” says Hemant. He has also befriended women in Azamgarh, with who he continues to chat, more in a friendly way than romantic.

Far from the world of Shweta and Hemant is newly minted Mumbaikar Samarth (24), who has used dating platforms on and off for more than a year. The story of each attempt is pretty much the same: Log on to the app, sift through the same profiles that he probably saw the last time he was there, don’t get good matches, get dejected, delete the app. His experience is very similar to that of many using apps like Hinge, Bumble, OkCupid, Tinder and others.

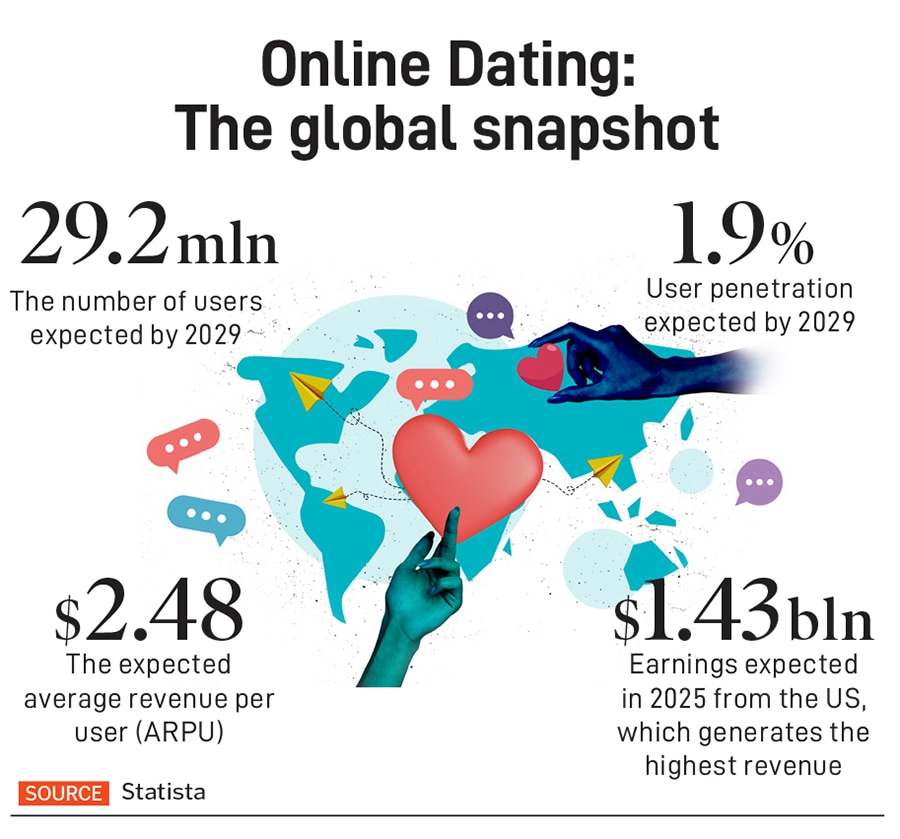

The global online dating market is estimated to grow from $11.02 billion in 2025 to $19.33 billion by 2033, according to Straits Research. The openness among urban Indian singles to online dating is extraordinarily high relative to anywhere else in the world, according to a top official at Match Group, Tinder’s parent company. Aditi Shorewal, communications lead for Tinder in India and Korea, says modern dating is all about meaningful possibilities, meeting people on your own terms and defining connection with authenticity. “Dating today is healthier, more honest, open, and focussed on mental well-being, compared to previous generations,” she says.

The Commitment Decade, an industry report conducted by dating platform Aisle, says that over 85 percent of users prioritise commitment as a relationship goal. One of the insights that Aisle’s research found is that key opinion influencers in the lives of young Indians have expanded beyond friends to now include siblings and even parents. This signals that older generations have begun to recognise platforms like Aisle as legitimate, respectable ways to meet a life partner.

According to research by investment platform smallcase, India is expected to become the world’s second-largest dating services market by 2027. A survey by Tinder found that 72 percent of young daters in India believe their generation is actively redefining traditional relationship norms, with 57 percent of them having met someone on a dating app and built a meaningful relationship; 45 percent view these platforms as the most common way to meet.

***

True as all of this might be, the examples of Shweta, Hemant and Samarth depict that the world of young people living in India’s metros and in smaller cities are as disparate as the rules of the dating game. It is not just that the price points at which US-based apps such as Bumble and Tinder operate are out of reach for most youngsters in small cities, but the fact that these foreign apps throw up matches within a specific geographical distance, something that doesn’t quite work for everyone.

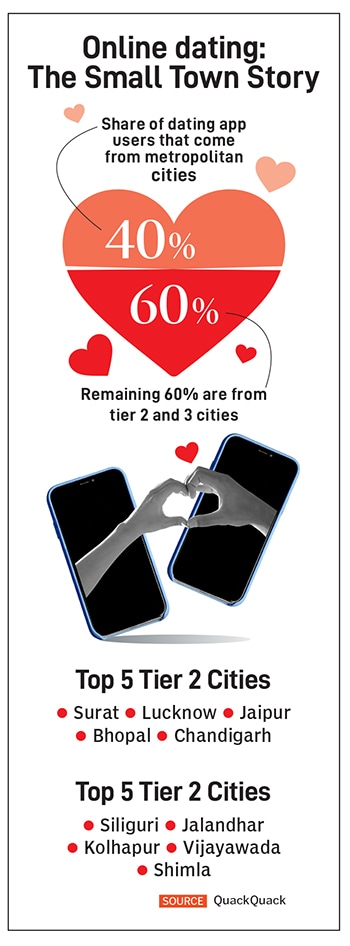

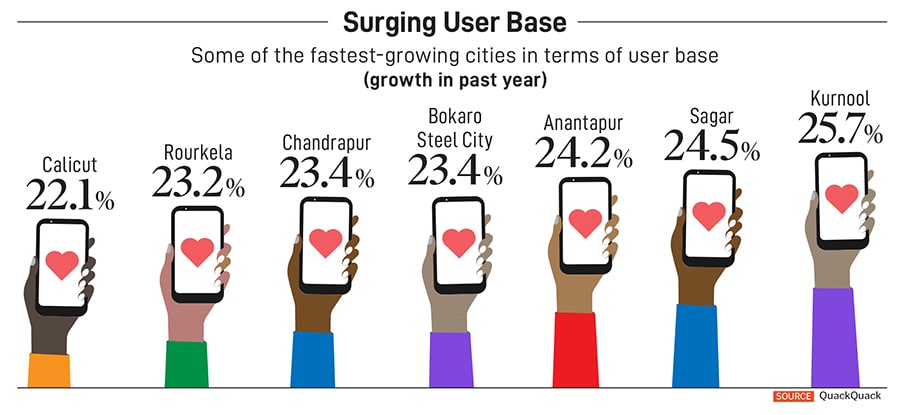

India-based online dating apps like QuackQuack, TrulyMadly etc. are filling in this small-town demand that bigger, metro-centric apps are unable to cater to. QuackQuack gets 60 percent of its users from small towns, while Aisle gets close to 30 percent from tier 2 and 3 cities. Aisle is trying to attract small-town folks with vernacular platforms that are more rooted in cultural and community nuances, including Arike (Malayalam), Anbe (Tamil), and Neetho (Telugu), which account for 45 percent year-on-year growth for the app.

The Indian apps are also easier on the pocket: A Bumble subscription costs Rs 2,000 a month and Hinge costs Rs1,600 for a premium account, while QuackQuack starts its premium fee from Rs 299, going up to a maximum of Rs 980 a month. Ravi Mittal, who founded QuackQuack in 2010 as a dating website, well before the US-based players got into the Indian market, and launched the app in 2014, is witnessing a rise in subscribers from during the Covid-19 pandemic.

QuackQuack added only about 1 lakh user in its first two years. During the pandemic, it grew to 20,000 to 24,000 sign-ups every day, and today it is steady at 10,000 to 12,000 daily sign-ups, claims Mittal. “We consider that the spending power of people from non-metros and the actual masses is much less. So, our prices are pretty low compared to the other platforms,” he says.

Aisle, founded by Able Joseph and Sarath Nair in 2014, has a weekly subscription fee that starts at Rs 99, and monthly fees between Rs 999 and Rs 1,200. Aisle, which started as a matrimonial app—a middle ground between casual dating apps and arranged marriage platforms—today has a strong national footprint, and more than 30 million registered members. Across its vernacular platforms, Aisle has around 1 million monthly active users and half a million weekly active users. Notably, the platform 25 to 30 percent women users, which is nearly double the industry average of 10 to 15 percent.

Explaining the success of Indian apps in tier 2 and 3 cities, Mittal says, “International apps have more of a one-shoe-fits-all solution. They're pretty popular in Bengaluru, Mumbai, Hyderabad and Delhi, where people are matching within a radius of 5 to 10 km.” In comparison, QuackQuack is more mass-based, with a pan-India sign-up. “We get users from Shillong, Bareilly, Kanpur and Kashmir. And the reason for this is that he requirement of the masses is very different from the people who use Tinder or Bumble.”

Mittal elaborates on one such differentiating factor: A lot of young people in tier 2 and smaller cities have had very little interaction with the opposite gender. “They see this as a very good opportunity to come online and have their first interaction with the opposite gender in a private setup without their family knowing. Dating apps offer them a space where they can not only interact with others from the comfort of their homes but also freely explore their own preferences, which is an integral part of emotional growth and maturity in a person.”

QuackQuack premium subscription brings in experts who can teach awkward newcomers the etiquettes of online dating. These experts are called ‘Human Matchmakers’ and are trained to help users find more compatible matches, give their profiles a makeover, write more engaging messages that result in better response rates, and help them have an overall finer dating experience both online and once they meet in-person. “Since most users are new to dating and dating apps, they are often unsure about how to interact with matches or approach them. Our matchmakers help make the process smoother and date successfully,” says Mittal.

He adds that users in small towns are specifically signing up to look for love and friendship, owing to the lack of options outside the app. “There's a whole taboo around interacting too much with the opposite gender in smaller cities. Dating apps offer a safe space for the same with the desired privacy.” An interesting observation he makes is that tier 1 daters are more inclined towards matches within their own city, while small-town users are open to intercity and interstate dating. The example of Hemant from Mau being case in point.

Another factor fuelling the growth of Indian dating apps in small-town India, is their acceptance of Indian societal norms that make youngsters seek long-term relationships, rather than casual dating. “We pioneered the Meaningful Dating Segment, where the focus shifts from volume to depth of compatibility,” says Chandni Gaglani, Head of Aisle Network.

She says a number of features on Aisle apps reflect its Indian DNA: Hyperlocal prompts, prioritising language alignment, a 2-step verification for safety, and more. “This creates a curated ecosystem for singles who want to date with purpose, date to get married. Our mission is clear: Honour the cultural aspirations of modern Indians while facilitating genuine, long-term connections.”

This focus on intent has driven Aisle’s strong business performance. After being acquired by Info Edge in 2022, Aisle’s portfolio has achieved 146 percent growth over the past two years. Gaglani says 20 percent of its users are in their late 20s to early 30s, while 60 to 70 percent of users on the vernacular-first platforms are premium subscribers. Overall, Aisle is on a steady path to profitability, having successfully reduced its burn rate by 42 percent.

***

Despite the ease that dating apps provide, Mittals feels users tend to think of them as a quick solution to going on a date; they overreliance on apps could lead to emotional difficulties and pressures. “Just by paying the subscription fee, or by liking a few hundred profiles, you should not expect that you will go out on a date or you know you would meet your match. It is like job interviews—it takes time, quality takes time. It's not a quick fix solution. It’s important to put in your best effort,” he cautions.

Shaurya Gahlawat, a psychologist, couple's therapist, and the founder of TWS, a mental health therapy practice, shares the experience of a client who perfectly captures the world of dating apps. “I keep thinking someone better is just one swipe away,” said the client.

When choice becomes unlimited, the mind struggles to commit and people develop a persistent fear of settling for someone less than the best. While Gahlawat’s was working on her master’s degree research on online-versus-offline dating, she discovered that apps disproportionately foreground physical attractiveness. The full-screen, photo-first design encourages people to evaluate appearance before personality or values. “Clinically, this has contributed to rising body-image concerns, self-comparison, and a subtle pressure to curate one’s identity as if it were an ad campaign. Many clients describe ‘micro-validation loops’; their mood rises or falls based on how many matches or likes they receive that week. Dating shifts from being a process of connection to becoming a measure of self-worth,” she says.

That said, Gahlawat explains that commitment issues or superficial relationships can’t be attributed to apps alone. Age, attachment histories, past relationships, cultural conditioning, communication styles and life circumstances all shape how someone approaches intimacy. “I work with a married couple who met on a dating app and have an exceptionally healthy bond; a reminder that the medium is only one part of the story. Expectations also evolve based on family upbringing, peer influence, celebrity culture, and social media, not just swiping.”

Another factor that comes into play is paying for better matches. Gahlawat does not see subscription models of apps as unethical or something that creates a sense of inequality; she believes that paying for visibility on an app is a digital extension of meeting someone at a boutique gym, an exclusive club, or a niche hobby class. “Ethical tension does arise in the emotional undercurrent. The business model leans heavily on two deep human vulnerabilities: The fear of being alone and the fear of missing out.”

With some clients, especially those experiencing loneliness, she has observed that the pressure to subscribe can blur the line between genuine connection and algorithmic scarcity. “When people start to feel that they must ‘pay to be seen’, it can distort their sense of self-worth and authenticity in the process."

To make dating apps more meaningful in the Indian context, Gahlawat points to a blend of psychological insight and cultural sensitivity: Clearer intention categories, stronger safety and verification systems, less gamified interfaces, prompts that foreground values, communication styles and personality, transparent algorithms and pricing, and slower, conversation-oriented design. “With thoughtful tailoring, online dating can align far better with the relational realities of Indian young adults,” she concludes.

First Published: Dec 11, 2025, 13:08

Subscribe Now