Until now, the earliest remains of modern humans found on the Continent were less than 45,000 years old. The skull bone is more than four times as old, dating back over 210,000 years, researchers reported in the journal Nature.

The finding is likely to reshape the story of how humans spread into Europe, and may revise theories about the history of our species.

Homo sapiens evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago. The new fossil bolsters an emerging view that our species migrated from Africa in several waves, beginning early in our history.

But the first waves of migrants vanished. All humans who have ancestry outside Africa today descended from a later migration, about 70,000 years ago.

Katerina Harvati, lead author of the new study, said it’s impossible to say how long the earliest Europeans endured on the Continent, or why they disappeared.

“It’s a very good question, and I have no idea,” said Harvati, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany. “I mean, this is the first time that we’ve found them.”

The skull first came to light in 1978, as anthropologists from the University of Athens School of Medicine explored a cave called Apidima, on the Peloponnese. They found fragments from a pair of skulls lodged in the roof of the cave.

The researchers freed a backpack-size rock containing the fossils, and then struggled for years to extract the bones.

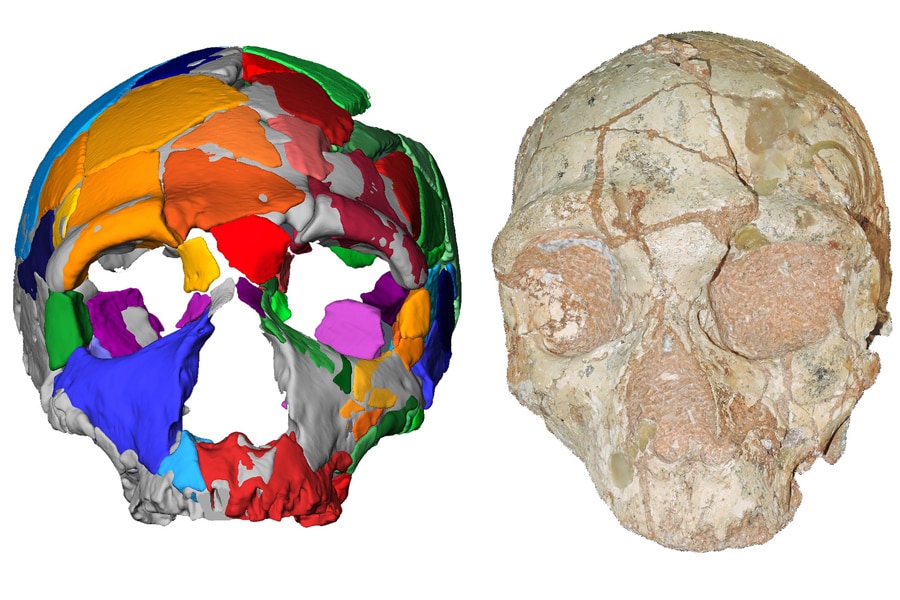

One of the fossils, called Apidima 1, turned out to be part of the back of a skull. The other, Apidima 2, consisted of 66 fragments from an individual’s face.

An early study of Apidima 2 suggested the fragments were about 160,000 years old, and so it seemed likely that Apidima 1 had fossilized around the same time.

That age made the two fossils much older than the earliest known evidence of our species in Europe. It seemed more likely that the skulls belonged to Neanderthals, who arrived in Europe about 400,000 years ago.

The Museum of Anthropology at the University of Athens invited Harvati, an expert on the shapes of human skull fossils, to take a closer look. She and her colleagues performed CT scans on the remains and then analyzed them on a computer.

When the researchers virtually reassembled the face of Apidima 2, they realized they were looking at a Neanderthal. But when the team analyzed the back of Apidima 1’s skull, they knew that they were dealing with something different.

In Neanderthals and other extinct human relatives, the back of the skull bulges outward. “It looks like when you put your hair up in a bun,” Harvati said.

But in our own species, there is no bulge. Compared with our extinct cousins, the back of the modern human skull is distinctively round.

To Harvati’s surprise, so was the back of Apidima 1’s skull. It also had other features found in Homo sapiens but not in other species.

Laura Buck, a paleoanthropologist at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the study, said Harvati and her colleagues made a compelling case. “That very round shape is something we tend not to see in other groups,” Buck said.

While Harvati and her colleagues were analyzing the fossils, Rainer Grün carried out a new study of their age. Grün, a geochronologist at Griffith University in Australia, analyzed tiny samples of rock retrieved from the two fossils.

Apidima 2, the Neanderthal, turned out to be 170,000 years old, just a bit older than the previous estimate. But Apidima 1, the Homo sapiens skull, was at least 210,000 years old — some 40,000 years older than Apidima 2.

That date makes the skull fragment the oldest modern human fossil not just in Europe, but anywhere outside Africa. The challenge scientists now face is to figure out how Apidima 1 fits into our ancient history.

Over the past 20 years, researchers have amassed a great deal of evidence indicating that human populations that live outside Africa today all descended from small groups of migrants who departed the continent some 70,000 years ago.

The journey is recorded in human DNA, and archaeologists have documented it by tracking the spread of human remains and tools from Africa.

But in recent years, researchers have discovered a few fossils that don’t fit the narrative. Last year, for example, researchers found a Homo sapiens jaw in Israel that is 180,000 years old.

Another clue came to light in 2017, in bits of DNA preserved in Neanderthal fossils discovered in Europe. Some of the genetic material appeared to have been inherited from Homo sapiens, not Neanderthals. The scientists speculated that our species reached Europe at least 270,000 years ago and interbred with Neanderthals there.

Harvati said that Apidima 1 and the DNA evidence both point to an early expansion of Homo sapiens into Europe from Africa. “It’s eerie how well it all fits,” she said.

It’s possible that the fossils in Israel belong to the same wave of modern humans from Africa, or perhaps to a later one. In either case, it seems that all those people disappeared.

One speculation is that Neanderthals moved into Greece and Israel, and outcompeted the modern humans they encountered. If so, things went differently during the later migration 70,000 years ago.

That wave of humans may have thrived outside Africa because they brought better tools. “If there’s an overarching explanation, my guess would be a cultural process,” Harvati said.

Greece may be a good place to test this idea. Southeast Europe may have served as a corridor for various kinds of humans moving into Europe, as well as a refuge when ice-age glaciers covered the rest of the Continent.

“This is a hypothesis that should be tested with data on the ground,” Harvati said. “And this is a really interesting place to be looking at.”

An undated combo image provided by Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen shows the Apidima 2 cranium, right, which consists 66 fragments from an individual’s face and was shown to be a Neanderthal skull, and its reconstruction, left. Another skull fragment found in the roof of a cave in southern Greece is the oldest fossil of Homo sapiens ever discovered in Europe, scientists reported on Wednesday, July 10, 2019. (Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen via The New York Times) [br]A skull fragment found in the roof of a cave in southern Greece is the oldest fossil of Homo sapiens ever discovered in Europe, scientists reported Wednesday.

An undated combo image provided by Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen shows the Apidima 2 cranium, right, which consists 66 fragments from an individual’s face and was shown to be a Neanderthal skull, and its reconstruction, left. Another skull fragment found in the roof of a cave in southern Greece is the oldest fossil of Homo sapiens ever discovered in Europe, scientists reported on Wednesday, July 10, 2019. (Katerina Harvati, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen via The New York Times) [br]A skull fragment found in the roof of a cave in southern Greece is the oldest fossil of Homo sapiens ever discovered in Europe, scientists reported Wednesday.