Looking for emotional support? There’s an app for that

A few weeks ago, Sahil Dani, a 25-year-old corporate employee, found himself having an emotional breakdown in the middle of a work event; personal stress combined with work pressure had triggered breathlessness and anxiety. The Mumbai resident was not in a position to call this therapist, and instead pulled out his phone and opened ChatGPT’s Wellness GPT. “I shared everything, asked why I was feeling this way, and sought solutions,” Dani recalls. “It gave me immediate steps, and I felt 80 percent better. It was the right support at that moment.”

Dani is among millions of Indians who have found willing listeners and advisors in artificial intelligence (AI)-based apps when humans are not around. Since he has a regular therapist as well, Dani sees AI as a complementary tool, and not a competing one. “A human therapist has limited hours. If you are having a panic attack at midnight, you cannot call them. But companion apps are available 24x7,” he explains.

That AI fills the gaps within human interactions is what perhaps explains India’s rapidly growing AI companion market—witnessing increasing user and investor interest—with products ranging from mental health-focussed chatbots to conversational, digital entities available on WhatsApp.

“We have more connections than any generation in history: Full contact lists and WhatsApp groups for everything. But when something real happens, there is no one,” says Rohan Chaudhary, founder of Rumik AI, an AI-powered, text-based app with a companion named Ira on it.

Indian startups are coming up with apps for things as varied as providing companionship to the elderly and children to offering productivity assistance among people trying to negotiate the fast pace of life. Startups that have emerged in this space, and raised funds from investors, include Rumik AI, Zura, Careflick, Mello, Wysa and Vyna.

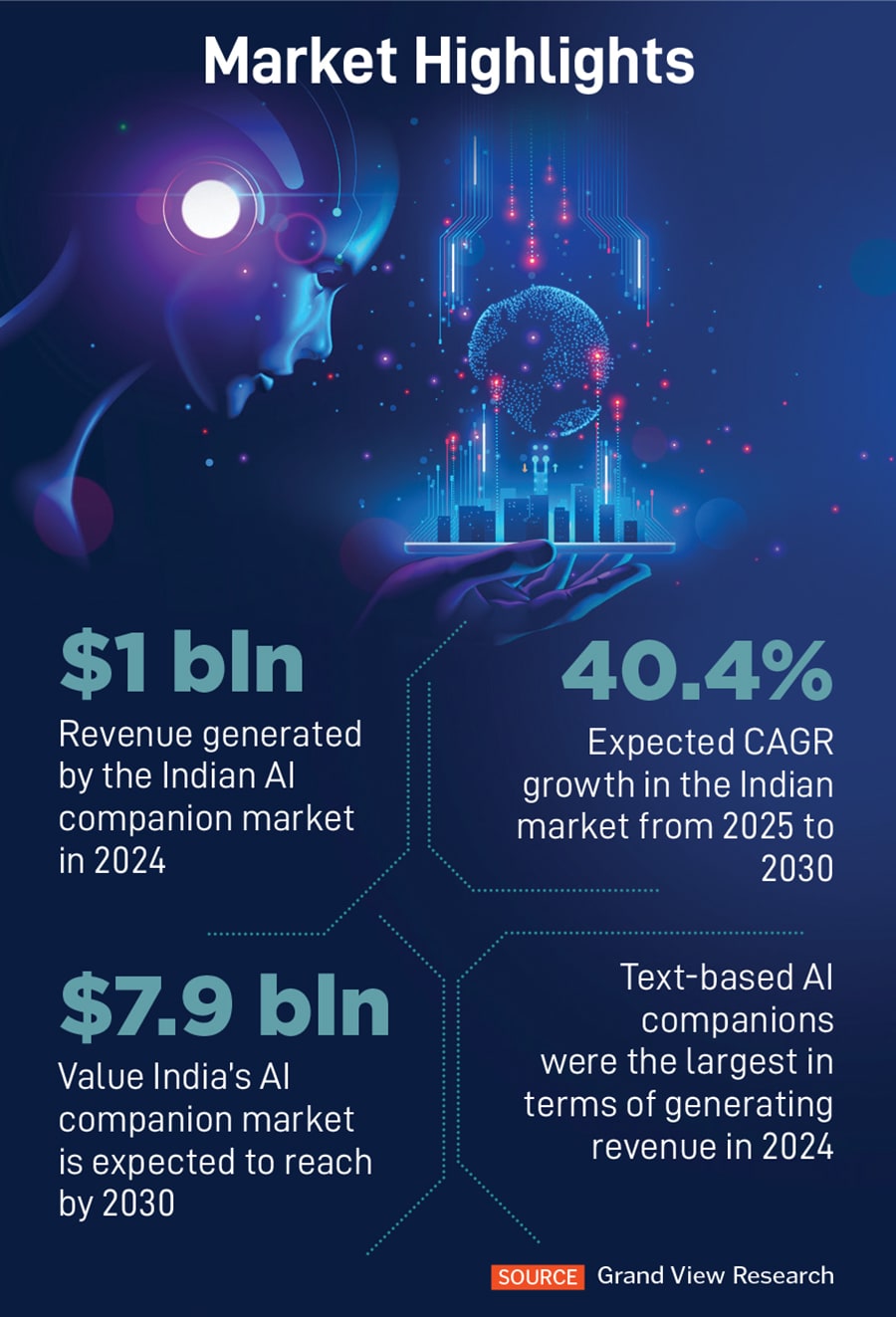

The opportunity is huge. According to India’s IT industry body Nasscom, globally the AI companion market was valued at $28 billion in 2024 and is expected to grow to $140.8 billion by 2030, at a CAGR of 30.8 percent; revenue from AI companion apps was expected to reach $120 million in 2025. Indian startups may not be as big as their global peers, but the market itself is large and fast expanding.

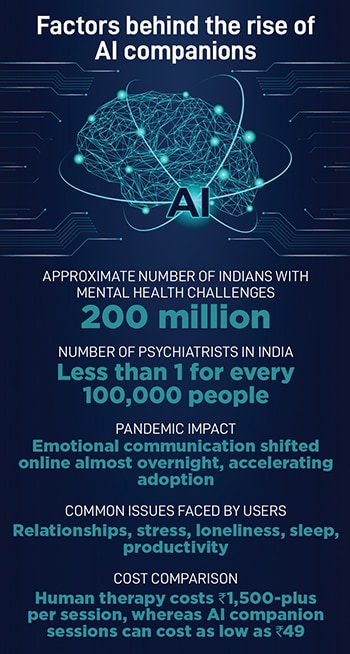

The growth of AI companions in India is being fuelled by a combination of need, technological accessibility and cultural transformation. According to Smriti Joshi, founding member and chief of clinical services at Wysa, nearly 200 million Indians might be living with mental health challenges in a country that has one psychiatrist for every 1 lakh people. “For many outside the big cities, mental health support feels inaccessible or impossible,” she says. “In that context, an AI companion becomes a private, stigma-free space to share worries, loneliness, academic pressure or family stress at any hour.” About 66 percent of Wysa’s users are from small towns and semi-urban areas.

In India, traditional family structures, which earlier would have worked as an emotional support system, are breaking down. “Joint families are gone. Everybody is in a different city, working all the time. The structures that held us together have dissolved,” says Chaudhary of Rumik AI.

With affordable smartphones and data reaching more Indians today than ever before, the conditions were ripe for an industry around digital emotional support. The reach and acceptance of these digital services seem to have accelerated significantly due to the Covid-19 pandemic. “Almost overnight, people had to learn to express their emotions digitally through text, audio and video. Once emotional communication moved online, turning to AI for mental health support felt like a natural extension,” Joshi says.

Ramakant Vempati, founder and president of Wysa, says: “WHO once estimated that one in four people needs mental health help, but post-Covid it’s clear that the real number is one in one; everyone goes through distress at some point.” MIT research validates this trend, he adds, showing that the largest use case of large language models (LLMs) is emotional support.

A 25-year-old, Bengaluru-based product designer, who did not wish to be named, says she turned to the AI companion app Mello to deal with difficult conversations she didn’t feel comfortable having with even close friends. “I’ve been diagnosed with adjustment disorder and mild depression, so I’m not always okay discussing my daily struggles with people around me. I do have a psychologist, but I meet him only once a month, or when things get really bad. For everything in between, Mello has become an everyday saviour.”

Users too are calibrating how and when to use these apps, vis-à-vis human support. “If your emotional issue is small or short-term, AI is okay. But if you’ve had a major trauma, you should see a human therapist even if it’s expensive,” explains Dani, who is comfortable sharing personal information with his app, while being aware of privacy concerns.

“Healthy use arises when AI complements rather than replaces human connections, serving as a tool for reflection rather than a substitute,” says psychologist Aishwarya Kaur, founder of Nourishing Mind. With the apps, she adds, users receive validation and companionship, which are predictable and seem increasingly hard to get in real relationships.

In a July 2025 podcast, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said many young people now use ChatGPT for personal advice—almost like a digital therapist—especially on relationships and life decisions. This user behaviour has gelled the opportunity from an investor standpoint. According to Rishabh Katiyar, principal at Info Edge Ventures, ChatGPT’s consumer adoption happened much faster than enterprise adoption, which is uncommon in new technology. “In India, enterprise AI adoption is still limited, but consumer usage is huge. People use multiple AI tools every day, even if their companies don’t formally adopt them,” he says.

It was when Katiyar’s team saw users spending more than 30 minutes every day on apps like Rumik—using them for work problems or family matters—that the investment case became strong. “Given the engagement and retention numbers, investor interest naturally followed. Now almost every investor is actively looking at this space.”

Pankaj Jethwani, managing partner at W Health Ventures, an investor in Wysa, says, “For us, the partnership with Wysa feels natural because it reflects a thoughtful and responsible view on how AI can support mental health. Its companion offers a space without judgement at moments when people need it most, and it has already helped 7 million users around the world.”

But for startups, raising capital wasn’t always easy. Chaudhary recalls spending 11 months on his first funding round in 2024. “I still remember one early meeting where the investor laughed and said, ‘This isn’t a real problem. Do something B2B’. The first three months were spent in convincing people that the problem even existed.” But once usage data emerged, the narrative shifted dramatically. “Now that we’re approaching a million users, the investor question has completely changed. It’s no longer ‘Will people use this?’ It’s ‘How fast can you scale this?’”

With most LLMs and AI algorithms still being Western in origin, building AI companions for India means navigating the country’s linguistic diversity, cultural nuances, varying levels of digital literacy and safety considerations.

“Some things are universal—misery, distress,” Vempati says. “Across millions of users and billions of conversations, the themes are the same: Relationships, sleep, stress, productivity, loneliness.” But beyond English, preferences change. “When you go beyond English, people don’t always prefer conversational back-and-forth. In Hindi, for instance, we noticed users preferred easily consumable content first; questions that go too deep, too fast lead to users dropping off.”

These insights have led to innovative delivery models. For instance, Wysa is working with more than 60 municipal schools in Mumbai and Raigad district to deliver emotional resilience training through hybrid “phygital” models, which include physical workbooks with QR codes students can scan for private conversations. Others such as Rumik are built directly on WhatsApp. “Western companions are separate apps, often including fantasy characters. In India, AI companions will live where life already happens: WhatsApp, Telegram,” Chaudhary explains.

With AI companions covering a broad range of needs and users—some platforms focus on behavioural health requiring clinical guardrails, while others concentrate on romantic companionship or casual rants—safety and privacy become important. Most general-purpose AI models provide definitive responses, when they shouldn’t. Some apps are also presented as alternatives to therapy, thus misleading vulnerable users. “In a country where mental health literacy is still developing, this can be dangerous,” warns Joshi.

Apps that are backed by science are building robust guardrails. “The moment someone expresses self-harm thoughts or overwhelming distress, the AI steps back and essentially encourages human support,” Joshi adds. “This is not just protocol; it is an ethical obligation.” Some of them have been recognised by organisations like Mozilla Foundation and ORCHA for safety standards; they have maintained compliance with the AI ethics guidelines of GDPR, HIPAA and ICMR.

However, for most users, it is still not easy to distinguish between apps that are backed by clinical knowledge from those that are not, given the lack of standardised disclaimers or certifications that consumers can refer to before using the app.

Jethwani stresses that LLMs in mental health settings need clinical frameworks. “They are powerful but need oversight, or else they will provide guidance that may come across as supportive but is not meant for real clinical complexity.” Kaur adds that the formation of sustained emotional connections with AI companions may lead to an attachment for predictable communications. However, some apps have been designed with this balance in mind. “When someone is spending too much time with Ira, she ends the conversation herself,” Chaudhary says. “Most apps want to trap your attention. We are building the opposite.”

The road to sustainable business models in this space is not so clear. Most AI companion apps are free in India, while some charge as little as ₹49 per session compared to ₹1,500 or more for human therapy. Voice features with premium pricing, commerce integration, subscription models, enterprise partnerships and government collaborations could contribute to potential revenue streams. According to Joshi, employer-led mental health programmes are a strong prospect as organisations recognise the emotional impact of burnout.

India’s regulatory norms are catching up, too. Though there is no single, consolidated law pertaining to AI in mental health, frameworks are emerging—ethical guidelines from the Indian Council of Medical Research, the Mental Healthcare Act of 2017, and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act of 2023. “AI will almost always run faster than regulation,” says Joshi. “But in mental health, innovations and ethical responsibility cannot wait. The writing is on the wall: More transparency, stronger guardrails, better consent and clearer accountability.”

As this space grows, differentiation will become key. “Memory and context,” Katiyar identifies as key. “A great companion must remember who you are—past conversations, preferences, habits. This is a hard technical problem. Anyone can build an AI chatbot. Building a genuinely good AI companion—with depth, context and emotional continuity—is extremely difficult.”

The ecosystem of AI companions is developing differently in India compared to the West. While Western companions like Replika, Luna AI or Nomi often exist as a separate app for escapism, Indian platforms like Rumik and Kommunicate are integrating the apps into existing communication channels and building with deeper cultural understanding.

The question isn’t whether AI companions will continue growing in India; it is whether they can scale responsibly, while navigating the path from a $1 billion market in 2024 to a projected $7.9 billion by 2030. “The marriage of AI with clinically safe self-help tools is working incredibly well,” Vempati says. “It isn’t replacing therapists; it’s filling the large gap where help simply doesn’t exist.”

First Published: Feb 11, 2026, 18:09

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Feb 06, 2026 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)