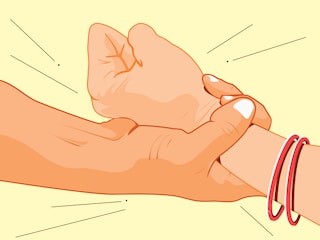

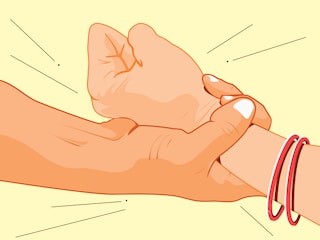

Domestic violence cases spike in lockdown

Women's rights organisations are seeing a spurt in complaints of violence from women since April. Activists demand a change in mindset and better implementation of existing laws to battle this global ...

In Uttar Pradesh, another woman conceived during the lockdown. Her family’s financial condition was so acute that she did not wish to have the child in such precarious times. Upset over this, her husband beat her mercilessly for a couple of days and sent her to her maternal home for good.

Incidents of domestic violence like these have been on the rise since the lockdown came into effect in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic in end-March. Community centres and non-government organisations (NGO) Forbes India spoke to admit to have seen a spike in calls for help between April and June. While they say many are follow-up cases, several women are reporting abuse for the first time and requesting immediate intervention.

“Domestic violence has always existed in society. It’s not a result of Covid… it has been exacerbated by the pandemic. What we are seeing is just the tip of the iceberg,” says Anuradha Kapoor, founder-director of Swayam, a women’s rights organisation, which has two crisis intervention centres in Kolkata and another on the outskirts of the city at Diamond Harbour. She says between March 20 and June 30, they offered help to about 1,300 women—900-plus previous cases and over 300 new ones. “It’s a huge number. It’s what we work with during the course of the year,” she says. In fact, at one of Swayam’s Kolkata centres, the number of cases reported almost doubled every month—from about 30 in usual circumstances to 50 in April, 65 in May and 130 in June.

In April, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) director-general, said that as people are asked to stay at home, the risk of intimate partner violence is likely to increase. According to WHO, one in three women globally experiences physical or sexual abuse from their partner in their lifetime. The pandemic has only proved to be an eye-opener to this scourge (see ‘Global Concern’).

Advocate Persis Sidhva says the extent of the malaise will be known only when the lockdown is completely lifted and women get the opportunity to step out of their homes to approach the relevant authorities. “Yes, there potentially could be an increase in domestic violence cases during the lockdown. However, the resources that survivors had to address their grievances substantially reduced during the ongoing crisis. Most people are able to give only helpline support,” says Sidhva, who offers her services to Majlis, a women’s rights organisation that provides legal assistance to victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, among other things.

“It shows people were waiting for access to some sort of service. The calls that we got pertained to only serious cases of abuse and women were seeking help despite so many difficulties and obstacles during the crisis,” says Amita Pitre, lead specialist, gender justice, Oxfam India.

The unforeseen lockdown created a situation where people were confined to their homes—sometimes dingy, cramped spaces—for months. It brought with it uncertainty and anxiety as many people lost their jobs or did not have a steady source of livelihood. The unavailability of alcohol during the initial phases also contributed to an unhealthy atmosphere in some families. The expectation that men should contribute to household chores was not taken too kindly in several cases. As a result, frustration crept in. None of these issues, however, can justify domestic violence, say those who have been on the ground, offering support to victims of assault. They say the problem lies in the way some minds are conditioned and the archaic ideas drilled in men when they are brought up.

Advocate Sidhva believes several factors compel men to turn abusive. “The constant need to be the dominating partner in the relationship… to exercise control,” she explains, adding that though domestic violence cases have gone up, it’s a positive sign that women are asserting themselves and realising what is happening with them is wrong.

A closer look at the cases that have come to the fore shows that the problem is not limited to the poor alone. It is rampant across all strata of society—from the metros to the villages and in slums and high rises. Women—employed or unemployed—have been at the receiving end of physical, mental, sexual and even economic abuse where savings have been snatched away. “A lot of discourse that has come through is about the middle class or lower middle class, and not the poor, though they have also dealt with violence. The poorest to the affluent have suffered,” says Pitre of Oxfam India.

The impossibility of face-to-face interactions with victims during the lockdown prompted NGOs and organisations to start additional helplines. “As soon as Swayam shut its offices, we got a counselling line. First there were three numbers… that increased to six and gradually nine. We offered counselling and psychotherapy as domestic violence impacts women’s mental health negatively and some women also had suicidal thoughts/attempts. At times we had to call the police to ensure they acted, and give legal advice too. We also provided counselling and therapy to children of survivors who are the hidden victims of domestic violence. But there’s a limitation to how much you can do over the phone,” says Kapoor.

Actor-filmmaker Nandita Das made a film on domestic violence called Listen to Her and shared helpline numbers at the end of it. Unseco came on board as a producing partner and other United Nations agencies also contributed in amplifying the message. “The helplines haven’t stopped ringing and it is no surprise that it [domestic violence] is being termed as a ‘shadow pandemic’. There is an urgent need to break the silence around these issues and so, on an impulse, I made the film,” Das tells Forbes India.

Akshara Centre roped in celebrities such as cricketers Virat Kohli and Ajinkya Rahane, and actors Anushka Sharma and Vidya Balan, among others, to spread the word against domestic violence. Its video campaign was launched in three languages—English, Hindi, Marathi. It has got over 5.5 million views. “The idea behind it was that we wanted influencers to take a stand. People have to recognise that it’s a crime and it has to stop. We also emphasised on the role of bystanders—they also should intervene,” says Dr Shah.

Oxfam India also used social media to share phone numbers that victims could call. Majlis, apart from offering legal aid, counselling and social support, provided for the education of the victims’ children and found jobs for survivors.

Such assistance can only bring temporary relief. Those fighting for women’s rights over the years want strict deterrents and harsher punishment for abusers. As of now, victims can approach a police station to lodge a non-cognisable offence or a first information report, depending on the severity of the abuse. They can also seek legal help under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA). But that’s not enough, they say. “We have a lot of laws in place. More laws is not the solution… from a women’s perspective, we need better and effective implementation of the existing laws,” says advocate Sidhva.

Many were disappointed that the courts did not take up these cases on priority basis. And that the police, too, did not offer unconditional support at times. Oxfam India says a woman who had left her house following abuse was stopped by the police and asked to return as the lockdown was in place. The shelter homes did not have the facilities to carry out Covid-19 tests, so many women had nowhere to go to. “The PWDVA should come under essential services. An entire machinery has to be functional for such women,” says Pitre.

Above all, experts call for a mindset change. “There needs to be a change in the way children, both boys and girls, are brought up. You can’t speak to boys when they are 20 or 25 and expect them to change their mindset,” explains Sidhva.

Kapoor of Swayam says the objectification of women should stop across media and institutions. “Everything that we read, hear or see insinuate the idea that women are weaker. We need to change that. We are not born with the patriarchy gene it comes through social conditioning,” she says. “Why can’t an ad agency advertise a car or any other product without objectifying women? Women’s products don’t need men to sell, so why do men’s products always need women?”

Change, it is rightly said, must begin at home.

First Published: Jul 25, 2020, 07:15

Subscribe Now