That made the 2010 divorce all the more poignant.

When Bajaj Auto parted ways with Kawasaki, it was the quiet uncoupling of a technology tie-up—there was no equity partnership between them. Bajaj had already discovered its own engineering rhythm with the Pulsar franchise and no longer needed a Japanese technology partner to define its future. When TVS ended its alliance with Suzuki, it was a mutual release of two engineering-led companies. TVS, fiercely proud of its indigenous capabilities, already possessed the DNA to innovate its way out of dependence.

Hero was different. Its success was inseparable from Honda’s technology. The Hero Honda brand was a monolith where consumers often did not know, or care, where Honda’s engineering ended and Hero’s manufacturing began. The company’s supply chain, R&D, and product planning were deeply interlocked with Honda’s ecosystem. Hero was, in effect, a commercial execution powerhouse with the largest volumes, the deepest distribution, and the most loyal customer base. It was not a technology company.

![]() When the joint venture dissolved, analysts predicted that Hero would bleed market share. They argued it had no viable future without the Japanese engine platforms, that it faced a steeper climb than any Indian automotive giant had ever attempted.

When the joint venture dissolved, analysts predicted that Hero would bleed market share. They argued it had no viable future without the Japanese engine platforms, that it faced a steeper climb than any Indian automotive giant had ever attempted.

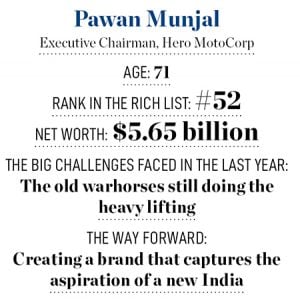

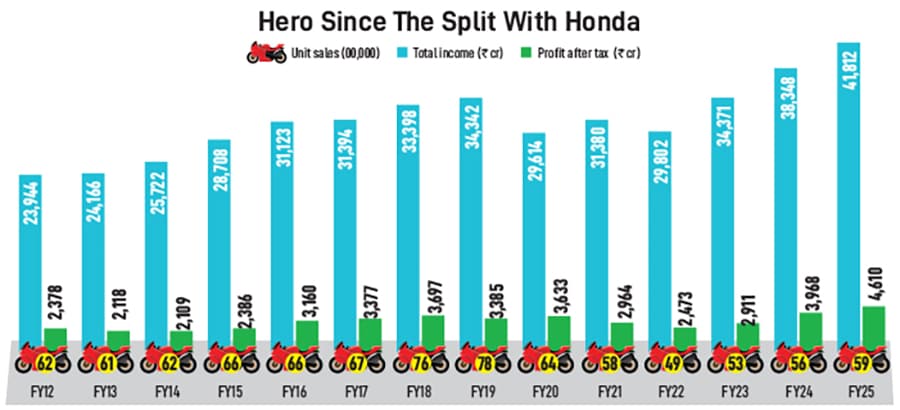

Fifteen years later, Hero MotoCorp remains the world’s largest manufacturer of two-wheelers. That is the story of how Hero’s magic has been kept alive by Executive Chairman Pawan Munjal, son of late Brijmohan Lall Munjal, founder of Hero Group. It is a complex narrative of resilience and the enduring power of the Indian rural economy mixed with a few missed opportunities.

Hero MotoCorp had not responded to questions for this story, nor to a request for an interview with Pawan Munjal by the time this story was finalised. The narrative is based on accounts from long-time insiders and individuals who have been associated with the company in the recent past.

![]()

The Cultural Divorce

To understand the trauma of the separation, one must understand the depth of the bond. It was not just about carburettors and pistons; it was about a shared culture of humility. During the golden years of the joint venture, the mutual respect between the Indian and Japanese teams created an atmosphere unlike any in the cut-throat automotive world. The relationship was so warm that Japanese executives often affectionately added “Munjal” to their surnames as a gesture of familial closeness. This camaraderie made the partnership feel less like a commercial arrangement and more like a shared mission.

The breakup, therefore, felt catastrophic. It wasn’t just business; it was a family splitting up.

The separation was not entirely Hero’s choice. Honda had entered India in the 1980s, when government restrictions made joint ventures the only viable path. But by 2010, with India emerging as the world’s second-largest two-wheeler market, Honda wanted the territory for itself. It already had Honda Motorcycle & Scooter India (HMSI), its fully owned subsidiary which was aggressively recruiting talent from Hero’s ranks. Honda steadily built its own identity in India even as the joint-venture agreement restricted Hero Honda’s ability to sell products outside India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and limited its freedom to develop technology independently. Adding to this asymmetry, Honda executives sat on Hero Honda’s board, giving them a clear window into the dynamics of the Indian market. Over time, the contours of the partnership shifted, and what began as collaboration increasingly felt like competition.

Inside Hero’s Dharuhera plant in Haryana, workers whispered the question that hung over the shopfloor like a fog: What happens when the Honda engines run out? There were fears that production lines would slow, vendors would switch allegiance, and the rural customer, who viewed “Hero Honda” as a single word, like salt and pepper, would be confused by the severance.

Also Read: It's a blessing to not be on that financial treadmill: Sridhar Vembu

Riot for the Seat

What the analysts missed, and what Honda perhaps underestimated, was the firmness of Hero’s grip on the Indian hinterland. It was a dominance built not just on engineering but also on trust. Veterans of the company recall the “wedding season riots” in states such as Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand. In these regions, a Hero motorcycle was not just a vehicle; it was a non-negotiable component of the dowry and social signalling system. When trucks arrived at dealerships, mobs would gather to claim a bike before it was even offloaded.

Desperate buyers would slash the motorcycle seats with knives. The logic was brutal but effective: Whoever damaged the seat claimed the bike, knowing they could simply buy a replacement seat later. Dealers, facing the prospect of actual riots and police deployment, had no choice but to sell the damaged unit to the person who had “marked” it.

Hero was a brand built on the rhythms of Indian life: Harvest, monsoon and the 45-day festival window stretching from Ganesh Chaturthi in Maharashtra to Bhai Duj in the North. Hero was the undisputed king of the festivals, often selling more units in a month than Bajaj and TVS combined. Its distribution machinery provided a moat no Japanese technology could cross overnight.

A farmer in Madhya Pradesh, when asked in 2011 why he stuck with the brand after the split, said: “Gaadi Hero ki hai, chalti rahegi (The vehicle is Hero’s; it will keep running).” Faith carried the company forward.

![]()

Rebuilding the Core

Though the heartland bought Hero time, Munjal knew nostalgia was a depleting asset. The company had to rebuild its core. He could either cling to the legacy momentum or build R&D from scratch. He chose the harder path. It required a psychological overhaul. Hero’s engineers, competent system integrators who had spent decades acting as custodians of Honda’s designs, had to become inventors.

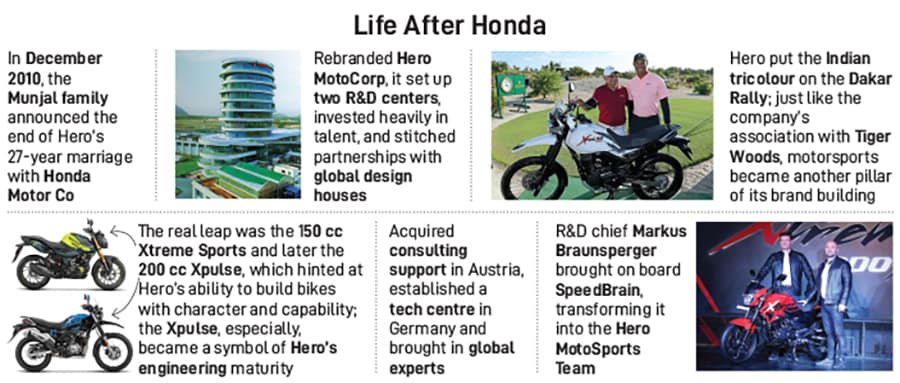

Hero set up two major R&D centres, invested heavily in talent and stitched partnerships with global design houses. It acquired consulting support in Austria, established a tech centre in Germany and brought in global experts.

Early tie-ups such as the one with Erik Buell Racing (EBR) in the US split opinion. Some saw the acquisition of a stake in EBR as a bold move to access high-performance technology; others called it reckless. Though EBR eventually collapsed, the partnership exposed Hero’s engineers to global product development cycles. The tie-ups with Magneti Marelli and Engines Engineering were not wildly successful.

New R&D chief Markus Braunsperger acted decisively. He brought on board SpeedBrain, transforming it into the Hero MotoSports Team. With this, Hero put the Indian tricolour on the Dakar Rally.

Just like the company’s association with Tiger Woods, motorsports became another pillar of brand building. This aligned perfectly with Munjal’s philosophy. He liked to work five to 10 years ahead in his head. He often gave the example of aspirational products such as Apple arriving late in India but being well-known. This was his rationale for global partnerships and high-visibility sponsorships—to position Hero as more than just a commuter brand and as a global player with aspiration capital.

The transformation from a manufacturing giant to a technology leader was not a straight line. Dealers were changed frequently in Peru, Argentina and Kenya.

Splendor-Passion Paradox

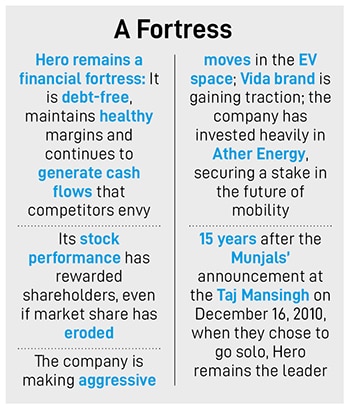

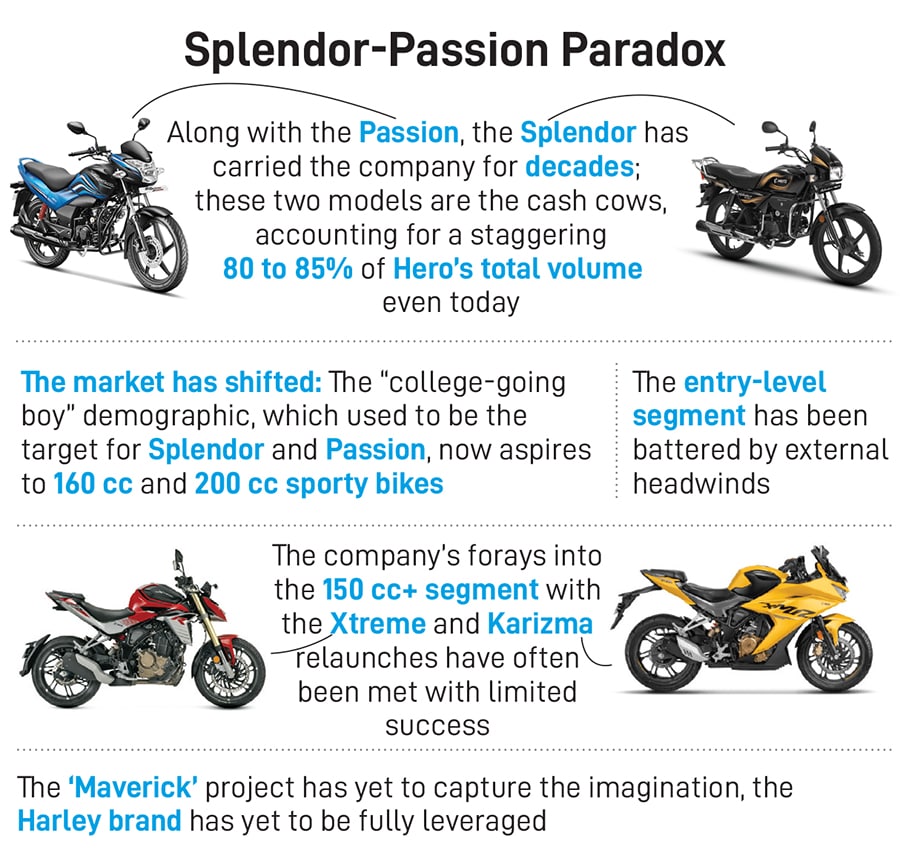

Along with the Passion, the Splendor has carried the company for decades. These two models are the cash cows, accounting for a staggering 80 to 85 percent of Hero’s total volume even today. They are masterpieces of utility: Frugal, indestructible and trusted.

![]()

On the flip side, every time Hero attempts to launch a fresh model or pivot the brand, the sales numbers tell a familiar story. The old warhorses are still doing the heavy lifting. The company’s dominance of the entry-level segment (where it once held a monopoly-like 74 percent market share) must be viewed against the shift in the market.

At least a section of the “college-going boy” demographic, which used to be the target for a Splendor or Passion, now aspires to have 160 cc and 200 cc sports bikes. The entry-level segment has been battered by demonetisation, the rise in cost because of the transition from BS-IV to BS-VI emission norms, and a punitive GST rate of 28 percent which got lowered only this year.

While Hero sits on a manufacturing capacity of 9 million units, sales have hovered between 5 and 6 million since the pandemic, off the highs of the 7.8 million in 2018-19.

![]()

Premium Promise

Bajaj ‘premiumised’ its portfolio with KTM and Triumph, and TVS built a racing DNA with BMW and Norton. Hero’s forays into the 150 cc+ segment with the Xtreme and Karizma relaunches have met with mixed results.

Insiders argue that the real test came not in branding but in product evolution. Hero’s first major independent motorcycle, the 110 cc Maestro scooter, was a cautious step. The real leap was the 150 cc Xtreme Sports and later the 200 cc Xpulse, which finally hinted at Hero’s ability to build bikes with character and capability. The Xpulse, especially, became a symbol of Hero’s engineering maturity, winning awards and building a cult appeal among off-road enthusiasts.

Hero, which handles Harley-Davidson’s distribution in India, had a licensing window to create a ‘Hero-Harley’ ecosystem similar to what TVS did with BMW and now with Norton. Yet, the ‘Maverick’ project, intended to be Hero’s answer in this segment, is not viewed by industry watchers as fully capitalising on the opportunity.

Brijmohan Lal Munjal, the late founder, had a quiet humility that permeated the organisation. When Bajaj launched a campaign mocking Hero for being slow and technologically behind, Hero’s marketing team bristled and prepared an aggressive counterattack. But the senior Munjal put a stop to it. “Hum aise nahi hain (we are not like that),” he told his people. Even in 2001, when Hero overtook Bajaj in annual sales, he refused to gloat. “We have not yet beaten Bajaj,” he said. “They’ve just been overtaken by us.”

Old-timers note that as Hero professionalised, the “family feeling” gradually became more process-driven, an evolution familiar to many organisations navigating scale. The Markus Braunsperger–Malo Le Masson phase introduced global discipline, best practices and new thinking, while also surfacing differing views on product direction. The debated redesign of the Passion became a reminder of the delicate balance between innovation and intuition.

The company had an extended stretch without a full-time chief technology officer. CEO Niranjan Gupta left to become CFO of Hindustan Unilever. His tenure at Hero, marked by financial discipline and a strong stock performance, was seen as part of a promising partnership with Pawan Munjal, often compared to successful leadership duos in Indian industry such as Nusli Wadia and Varun Berry at Britannia. The task of aligning financial, product and technology vision now enters a new chapter.

That next chapter is now taking clearer shape with the appointment of Harshavardhan Chitale as Hero MotoCorp’s CEO, effective January 5, 2026. A former global CEO of Signify’s Professional Business and an IIT-Delhi alumnus, Chitale brings extensive experience across technology and manufacturing sectors.

Industry watchers view Chitale’s arrival as an opportunity for Hero to deepen its technical leadership bench and reconnect its product ambitions with a sharper innovation agenda. His appointment marks a significant moment, one that could help bridge the gap between the company’s strong financial foundation and its aspirations for product and technology-led growth.![]()

Pawan Munjal with a Vida. The brand of scooters is gaining traction, occasionally overtaking rivals like Ola’s models in monthly sales in specific regions;

Photo by Pier Marco Tacca / Getty Images

Hero’s performance

Hero remains a financial fortress. It is debt-free, maintains healthy margins and continues to generate cash flows that competitors envy. Its stock performance has rewarded shareholders, even if market share has eroded.

The company has made decisive moves in the electric space. After a slow start, its Vida brand of scooters is gaining traction, occasionally overtaking rivals like Ola’s models in monthly sales in specific regions. The company has invested heavily in Ather Energy, securing a stake in the future of mobility.

Hero’s magic did not vanish with Honda; it changed form. The company has proven it can withstand shocks that would have hobbled lesser firms. Fifteen years after the Munjals’ announcement at the Taj Mansingh on December 16, 2010, when they chose to go solo, Hero remains at the top. The company faces its share of pressures, but its sustained leadership is worthy of recognition.

As it enters its 15th year of ‘independence’, can Hero produce ‘another Hero’? Can it create a brand that breaks the commuter stereotype and captures the aspiration of the new India? The Splendor provides a safety net, but Hero cannot afford to slumber.

The task ahead is not merely technological. It requires fixing the go-to-market execution. It requires moving up the chain to higher-end motorcycles more effectively. It requires sustaining the old humility and ear-to-the-ground sensitivity that Brijmohan Lal Munjal instilled in the company.

If Hero can combine its unmatched scale with a renewed spirit of innovation, the next 15 years could be a story of dominance reclaimed.

For now, the massive ship is turning slowly but it sails on. The ‘wedding riots’ may be a thing of the past, but in millions of Indian households the sentiment remains: Gaadi Hero ki hai. The challenge for Pawan Munjal and his team is to ensure that for the next generation, that sentence is spoken with pride, not just nostalgia.

Amrit Raj is a former journalist, author of Indian Icon—A cult called Royal Enfield, and Chief Marketing Officer of Zetwerk Manufacturing Businesses