Graphite India: Historical arc

A shift in steel technology has a family-run leader in graphite electrodes humming. Even a wary patriarch is making bigger plans

We are in a venture—not an adventure, says Krishna Kumar Bangur, Graphite India chairman

We are in a venture—not an adventure, says Krishna Kumar Bangur, Graphite India chairman

Image: Rajat Ghosh for Forbes

China’s decision in 2017 to replace highly polluting blast furnaces with electric arc furnaces to make steel reverberated all the way to Kolkata, where Graphite India, a maker of graphite electrodes, is headquartered. The producer of this niche carbon product for the electric-arc process suddenly found itself in the spotlight as global demand spiked.

The company’s shares have tripled in rupee terms in the past 12 months, earning Krishna Kumar Bangur, who owns a 65 percent stake, a debut spot on the top 100. He’s listed at No 91 with $1.7 billion. Despite the windfall, Bangur, 58, has jubilation on hold. “It’s a feel-good factor—nothing else,” he says from his office in Kolkata’s busy Chowringhee Road. “We cannot afford to lose our heads. I feel more of a sense of responsibility now.”

The company’s revenue doubled to $507 million for fiscal 2018, and it reported a 14-fold rise in net profit to $159 million. Thanks to that stellar performance, it made a maiden appearance on Forbes Asia’s Best Under a Billion companies list this year. But with $223 million cash on the books—as of the June quarter—Bangur is still cautious. “We won’t mindlessly spend this cash,” he says. “We are in a venture—not an adventure.”

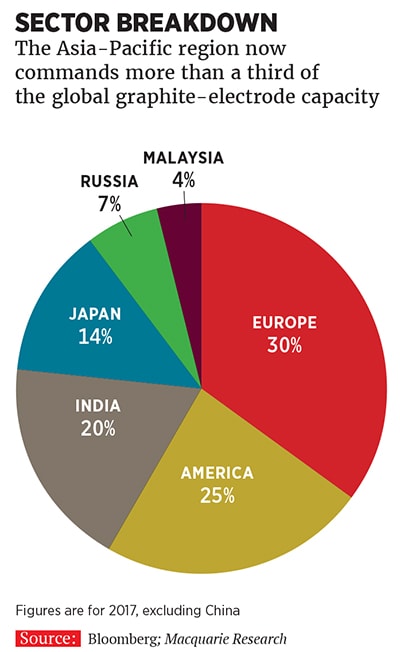

Bangur believes that it was this conservative approach that contributed to the transformation of his nondescript maker of graphite electrodes into the world’s third-largest outfit, notching a 12 percent global market share (excluding China, which has relied on a lower-grade technology than more developed economies).For all China’s push on electric arc furnaces—it is aiming to have 20 percent of its steel made in lower-polluting mills, from 9 percent currently—it holds no prospect of direct sales for the otherwise internationally minded Graphite India. The insular industry there doesn’t invite entry. As Bangur laments, “China is a black box. Sometimes nobody has a clue as to what China is all about.”

But its winds blow far. Beyond the furnaces shift, China also cut back on steel exports—out of its own environmental concerns as well as pushback from the European Union, the US and India on steel dumping. This stoked steel production in other parts of the world where electric arc furnaces are used for 45 percent of steelmaking.

Over the next five years, demand for graphite electrodes is expected to outstrip supply, keeping prices high. (Capacity is expected to grow by 8 percent annually, but demand should grow by 12 percent.) “We see this uplift as structural,” noted Sumangal Nevatia in a Macquarie Research report in June. “With no substitute, growing demand and limited new supply, graphite electrodes are now more a ‘strategic resource’ than a ‘commodity.’&thinsp”

The China turn came when the graphite electrode industry was recovering from a spell of weak demand. From 2011 to 2016, China was pumping steel—made in blast furnaces—into global markets and had racked up a 50 percent market share. This caused demand for graphite electrodes to tumble and prices to halve. As factories across the globe started to shut, 20 percent of global capacity (excluding China) was wiped out. The industry started consolidating, and in that shuffle Graphite India, which used to be the fifth-largest player, moved to No 3.

While the rest of the industry bled, Graphite India continued to make profits because it wasn’t saddled with debt. The company sells more than half its volume in India but also exports to the US, Europe, the Mideast and Southeast Asia. “We’ve never made a loss in our entire history,” notes Bangur. He even added 20,000 tonnes of capacity at a plant in West Bengal at a cost of $43 million in 2014.

Indian rival HEG—now the fourth-largest player in the world—was also hit by the downturn and suffered losses in fiscal 2016 (for the first time in 39 years) and fiscal 2017. But the Delhi company has since recovered to make net profits of $166 million for fiscal 2018. (HEG’s chairman and managing director Ravi Jhunjhunwala also debuts on the 2018 Forbes India Rich List at No 99 with a fortune of $1.5 billion.)

Even though graphite electrodes are being used in lower-polluting plants, there are environmental concerns about the components’ factories themselves. In September, residents near Graphite India’s Bengaluru plant protested against air emissions and the Karnataka state pollution control board conducted an inspection. A report is awaited. The board had issued a closure order in 2012, which the company contested in an appeals court. It won, but the residents appealed to the National Green Tribunal (for cases relating to environmental protection) and the matter is pending.

Scalability is also a question. The limiting factor is access to the key raw material, needle coke, which is made from crude and is sourced from a clutch of manufacturers in the US and Japan. The limited supply is also subject to diversion to lithium-ion battery makers.

So Bangur is looking at diversifying beyond graphite electrodes into value-added graphite and carbon products. In September he agreed to buy a 46 percent stake in Graphene Corp of the US for up to $18.6 million in cash. Graphene is a carbon-based product that could be used in everything from touchscreens to energy storage and aerospace. “It’s a new idea,” says Bangur. “If it develops well it can become another Graphite India. But it has many years to go.”

Bangur’s life in business goes back to 1976 when he turned 16. A fifth-generation scion of a storied family that was into everything from jute to real estate, he got an early introduction to different businesses from his elders even as he studied commerce as an undergrad. He also worked on many a shop floor.In 1991 the extended Bangur family split and his branch got the electrodes business, among others. Another prominent Bangur clan, led by patriarch Benu Gopal Bangur (No 22) of Shree Cement, inherited the cement unit.

Post-split, a partnership with Great Lakes Carbon of the US dating to the 1960s unravelled. “We were only a domestic player until then and were not even equipped to produce high-grade electrodes,” recalls Bangur. “We had to change the product mix, go into new markets and build market share.”

His father’s death in 1994 propelled him to the hot seat at the age of 34. “I became head of the family too early in my life—but such is life,” he says. (He has an older sister who is not involved in the business.)

Graphite India as it is now was formed in 2001 through the merger of two companies. Bangur slowly built up and in 2004 took over a German electrode-making company in bankruptcy and turned it around.

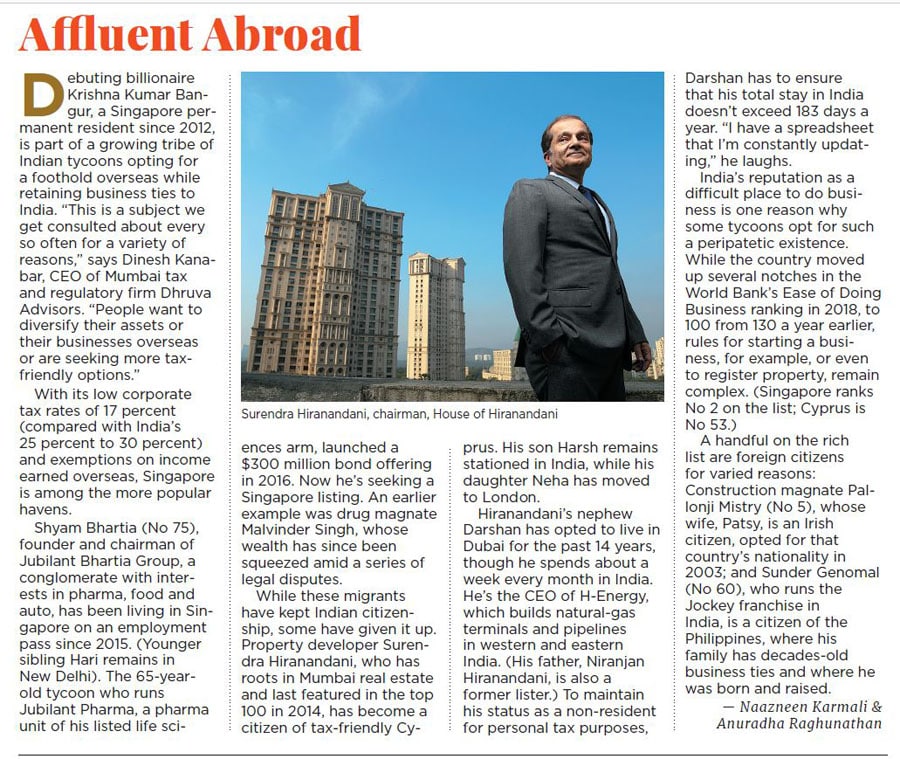

To further his business interests Bangur took permanent residency in Singapore in 2012, joining a growing tribe of Indian tycoons who have sought such dual credentials. “We may be looking at global opportunities, and it will be easier to raise capital internationally,” he says.

For all his instinctive caution, the veteran of a long-volatile sector sees new light. “This change is quite different from past changes,” Bangur says. “I am convinced that this is here to stay.”

First Published: Nov 29, 2018, 10:40

Subscribe Now