Health vs hype: Why ORS is a medical treatment and not a sugary drink

The recent ban on drinks mislabeled as ORS follows the earlier crackdown on ‘health drinks’

On October 14, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) issued an order that banned the use of the term ‘ORS’—short for oral rehydration solutions—on any drink that did not follow the medical formula prescribed by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The move, upheld by the Delhi High Court, followed a public interest litigation (PIL) that was filed by Dr Sivaranjani Santosh, a Hyderabad-based paediatrician, who started a campaign against the mislabeled drinks in 2017. “Rehydration is core to paediatrics,” she tells Forbes India. “ORS is a life-saving medicine, not a sugary drink.”

Sivaranjani’s campaign had begun in 2017 after she began to notice that her patients who were suffering from diarrhoea were not showing signs of improvement after being prescribed ORS to treat dehydration. The children’s parents insisted they were using ORS products, and what they showed her were products labelled as ORS drinks but containing nearly 10 times the sugar of the WHO-approved formula.

Sivaranjani found these products were approved as beverages under FSSAI, rather than as drugs under the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO). She began writing to both regulators in 2021, and, after receiving no corrective action, filed a PIL in the Telangana High Court, naming the Union Health Ministry, FSSAI, CDSCO, and several manufacturers. Her campaign finally resulted in the October 14 order.

Also Read: India’s cough syrup deaths raise concerns over drug safety standards

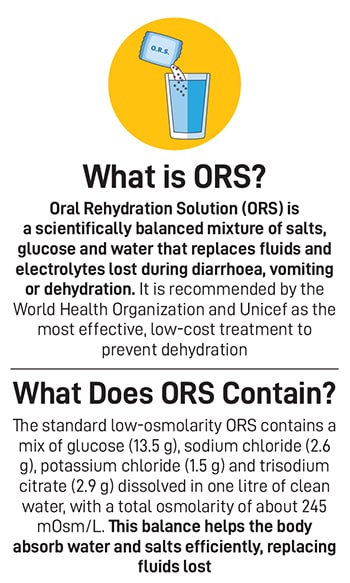

ORS is a drug that is used globally, and recommended by WHO and Unicef, to treat dehydration that arises from various diseases such as diarrhoea, vomiting, and other infections (see box). It is made of a specific formula, recommended by WHO, and cannot be substituted with any other formula. Unlike beverages such as soft drinks and fruit juices that are certified by FSSAI, which checks and certifies food products for safety standards, ORS products need to be certified by CDSCO for formulations and therapeutic standards.

However, in India, several brands that used ORS labelling were bypassing CDSCO regulations by registering as food products under the FSSAI. The result: Drinks and powders that were labelled as ‘ORS’ but often with high levels of sugar, preservatives, and artificial

flavours.Following Sivaranjani’s campaign, in April 2022, FSSAI declared that use of ‘ORS’ on food-licensed drinks amounted to misbranding under the Food Safety and Standards Act (FSSA), 2006. In July, 2022, however, it allowed companies to retain the term, but with disclaimers. With consumers largely ignoring disclaimers, complaints against the mislabelling continued, and FSSAI finally banned the misuse this October. “At least now there won’t be ORS on any label unless it’s WHO-recommended,” says Sivaranjani, "but companies can be devious; they might rename products DRS or QRS [to look similar to ORS]. The fight isn’t over.”

Other physicians add that the regulation continues to confuse consumers. Dr Farah Ingale, director, internal medicine & diabetologist, Fortis Hiranandani Hospital, Vashi, Mumbai, says, “It’s common for patients to opt for retail electrolyte or malt-based drinks instead of prescribed ORS. Most don’t understand the difference. But since the recent crackdown, patients are becoming more discerning.”

Manisha Kapoor, CEO and secretary general of the Advertising Standards Council of India, says complaints related specifically to beverages making “ORS-like” or rehydration claims remain rare, but vigilance is high. “Most advertisers now position their products as lifestyle or nutritional beverages rather than therapeutic or medical products, reflecting a growing awareness of regulatory and ethical boundaries,” she says.

Malt-based drinks marketed as ‘health drinks’ had come under scrutiny a few years ago when, in 2023, a video by YouTuber

Revant Himatsingka, known as FoodPharmer, highlighted the high sugar content in some of them. The video showed that certain variants of these drinks contained 45 to 50 percent sugar by weight.The video triggered a public outcry and put long-ignored marketing practices under scrutiny. It prompted the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) to review how such beverages were being marketed without clear scientific backing.

In 2024, the FSSAI issued an advisory to all ecommerce platforms stating that a ‘health drink’ is not defined or standardised under the FSSA, and that many dairy-based, malt-based and cereal-based beverage mixes were being promoted as ‘health drinks’ or ‘energy drinks’, which could mislead consumers. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry reinforced the directive, instructing ecommerce platforms to remove such beverages from their ‘health drinks/energy drinks’ listings. Following these, Hindustan Unilever Ltd (HUL) dropped the term ‘health drink’ from the packaging and advertising of its brand Horlicks, reclassifying it as a ‘functional nutritional drink (FND)’.

Dr Kumar Salvi, consultant, paediatrics & neonatology at Fortis Hiranandani Hospital, Vashi, Mumbai calls it “a semantic loophole that sustains misleading marketing”. “When parents hear ‘health drink’, they assume it’s medically validated,” he says. “But most of these products are high in sugar and additives..”

Dr Pradeep Suryawanshi, director, neonatology & paediatrics at Sahyadri Hospitals Momstory, Pune, adds: “These drinks are often promoted as nutritious, but many contain maltodextrin, stabilisers and artificial flavours that can dull appetite for natural foods.”

First Published: Nov 20, 2025, 14:28

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Nov 28, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)