Business intelligence for dummies

Sorry, PhDs. Dean Stoecker's analytics software, Alteryx, can turn almost anyone into a data scientist. And it's turned him into a billionaire

Slow & steady: Dean Stoecker had to wait for the market to catch up to his idea

Slow & steady: Dean Stoecker had to wait for the market to catch up to his idea

Image: Courtesy: Alteryx[br]Sun Tzu meets software in mid-August at downtown Denver’s Crawford Hotel. The floors are terrazzo. The chandeliers are accented with gold. And Dean Stoecker, the CEO of data-science firm Alteryx, has summoned his executives for the annual strategy session he calls Bing Fa, after the Mandarin title of The Art of War. “Sun Tzu was all about how you conserve resources,” says Stoecker, 62. “How do you win a war without going into battle?”

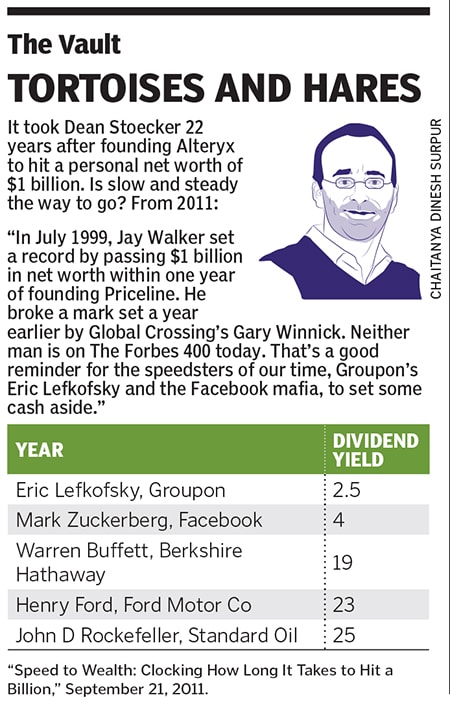

Stoecker knows something about conserving resources. He co-founded Alteryx in 1997, when the data-science industry scarcely existed, and spent a decade growing the firm to a measly $10 million in annual revenue. “We had to wait for the market to catch up,” he says. As he waited, he kept the business lean, hiring slowly and forgoing outside investment until 2011. Then, as “big data” began eating the world, he raised $163 million before taking Alteryx public in 2017. The stock is up nearly 900 percent since, and Stoecker is worth an estimated $1.2 billion.

“People ask me, ‘Did you ever think it would get this big?’” he says. “And I say, ‘Yeah, I just never thought it would take this long.’”

Alteryx makes data science easy. Its simple, click-and-drop design lets anyone, from recent grads to emeritus chairmen, turn raw numbers into charts and graphics. It goes far beyond Excel. Plug in some numbers, select the desired operation—say data cleansing or linear regression—and presto.

There are applications in every industry. Coca-Cola uses Alteryx to help restaurants predict how much soda to order. Airlines use it to hedge the price of jet fuel. Banks use it to model derivatives. Data analysis “is the one skill that every human being has to have if they’re going to survive in this next generation,” says Stoecker. “More so than balancing a chequebook.”

Alteryx’s numbers support that forecast. The company, based in Irvine, California, generated $28 million in profit on $254 million in revenue in 2018, and Stoecker expects to hit $1 billion in annual sales by 2022.

Stoecker grew up the son of a tinkerer. His father built liquid nitrogen tanks for Nasa before quitting his job to sell “pre-cut” vacation homes in Colorado. He made them himself. “It was literally just him nine months of the year, and he would cut wood for 50 buildings,” Stoecker recalls. As a teenager he joined his father, and by the time he arrived at the University of Colorado Boulder to study economics, he was able to pay his own way.After graduating in 1979, Stoecker earned his MBA from Pepperdine, then took a sales job in 1990 at Donnelley Marketing Information Services, a data company in Connecticut. There he met Libby Duane Adams, who worked in the firm’s Stamford office. Seven years later, the pair founded a data company of their own, which they cumbersomely named Spatial Re-Engineering Consultants. (A third co-founder, Ned Harding, joined around the same time Stoecker, who came up with the idea, took the lion’s share of the equity.)

SRC’s first customer, a junk mail company in Orange County, paid $125,000 to better target its coupons. “We were building big-data analytic cloud solutions back in 1998,” says Stoecker, when many businesses were barely online and terms like “cloud computing” were years away.

SRC was profitable from the outset. “We didn’t spend ahead of revenue. We didn’t hire ahead of revenue,” says Adams, sitting in a remodeled 1962 Volkswagen bus at Alteryx headquarters, theoretically a symbol of the company’s journey. “We never calculated burn rates. That was a big topic in the whole dot-com era. We were not running the business like a dot-com.”

In 2006, as part of a pivot away from one-off consulting gigs, SRC released software to let customers do the number-crunching themselves. They named the software Alteryx, a nerdy joke for changing two variables simultaneously: “Alter Y, X.” Stoecker made Alteryx the company name, too, in 2010.

The market was still small. To grow revenue, “we just kept raising the price of our platform,” Stoecker says. In the beginning, Alteryx sold its subscription-based software for $7,500 per user by 2013 it was charging $55,000. The next year, as Stoecker felt demand growing, he slashed prices to $4,000. Volume made up for the lower rate. Today Alteryx has 5,300 customers. “We immediately went from averaging eight, nine or 10 [new clients] a quarter to north of 250,” he says.

Although data mining and data analytics is a long-established field, encompassing a slew of startups as well as giants like Oracle and IBM, “we see almost no direct competition,” Stoecker insists.

“It’s a pretty wide-open field,” says Marshall Senk, a senior research analyst at Compass Point Research & Trading. “The choice is you buy a suite from Alteryx or you go buy 15 different products and try to figure out how to get them to work together.”

Inside Alteryx’s offices, Stoecker pauses in front of a time line depicting his first 22 years in business. “The good stuff hasn’t even occurred yet,” he says. “I’m going to need a way bigger wall.”

First Published: Nov 14, 2019, 13:26

Subscribe Now