TS Kalyanaraman's golden touch

The founder of Kalyan Jewellers made a fortune selling wedding jewellery in India. Now, as the price of gold booms, he faces the prospect of value-conscious customers amid an ambitious expansion push

On a bustling street in the southern city of Chennai on a weekday afternoon, Kalyan Jewellers India’s 1,860-square-meter flagship store is buzzing with customers, from a couple in their 30s to Indian expats visiting from the US.

Attentive sales assistants offer to help them try on any piece that catches their eye from the wall-mounted rows of glittering gold necklaces and countertop displays of bangles, earrings and rings. The range starts from under $200 for simple gold rings going up to as much as $60,000 for elaborate wedding jewelry, some studded with diamonds, rubies and emeralds. Behind locked glass cases are even more ornate collections that run as high as $120,000.

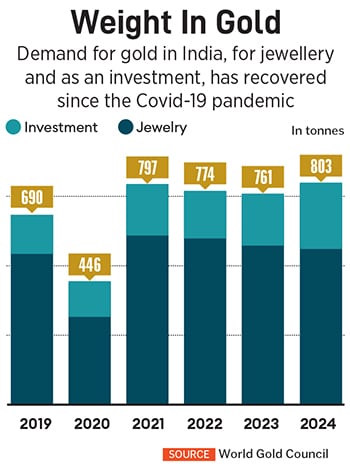

In gold-obsessed India, where households collectively hold 34,600 tonnes of gold valued at nearly $3.8 trillion, according to Morgan Stanley estimates, Kalyan is the country’s second-biggest listed jewellery retailer by sales. And the company has lately been on a hot streak.

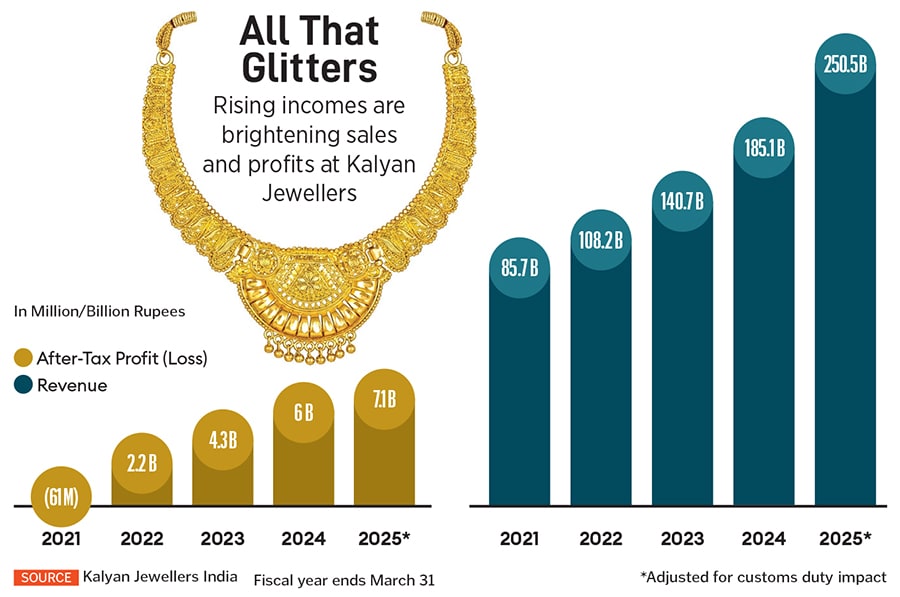

The top line has more than doubled in the past five years to ₹250.5 billion ($2.9 billion) in the year ended in March, lifting after-tax profit fivefold to ₹7.1 billion. That was even before President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs on US imports sent the price of gold—a so-called safe-haven investment—soaring to a record $4,000 an ounce in early October. This, in turn, has pushed up the cost of jewellery, posing a challenge to retailers such as Kalyan to find ways to reduce the sticker shock faced by their customers.

Kalyan’s billionaire founder and managing director TS Kalyanaraman isn’t perturbed. “There’s no full stop to growth,” says the 78-year-old (net worth: $3.1 billion). He’s seated in his office at corporate headquarters in Thrissur, a town in the southern Indian state of Kerala known for its temples as well as its gold artisans and traders.

Helped by his sons, Rajesh, 50, and Ramesh, 48, who work at the company as executive directors, Kalyanaraman has built a network of nearly 400 stores nationwide and another 40 stores in the Middle East and the US. With gold prices rocketing, analysts say Kalyan is emphasising more budget-friendly options in its range that are lighter in weight as well as on the pocket. Kalyan’s ability to react quickly to market changes rests on an in-house design team in Mumbai and a cohort of nearly 900 contract manufacturers across the country.

These moves “cushion the impact,” says Manoj Menon, research head at Mumbai-based ICICI Securities. It projects Kalyan’s revenue and after-tax profit are set to climb 28 percent and 38 percent, respectively, on an annual compound basis over the next two years.

Wedding jewellery makes up nearly 60 percent of Kalyan’s sales, which includes temple-inspired designs, adorned with Hindu deities like Lakshmi (Goddess of wealth) and Ganesha (the elephant God), and other religious motifs. Gifting gold jewellery to daughters is a long-held custom in Indian families. Gold jewellery is considered as part of stree dhan, recognised by law as a woman’s exclusive property, which can’t be claimed by her husband or his family. Apart from weddings, annual festivals such as Akshaya Tritiya and Diwali are also observed as auspicious occasions to buy the metal in some form.

With gold embedded deeply in Indian culture, the long-term outlook for the jewellery market is expected to retain its sheen. Investment firm Nomura projects that it could hit $150 billion in the next eight years from $90 billion today. This forecast is based on the rise in double income households and the growing population of young Indians in their twenties—a segment of potential customers for Kalyan’s wedding jewellery—that’s estimated to touch 390 million by 2030.

With an eye on future demand, Kalyanaraman is pushing forward with expanding Kalyan’s retail footprint, adding 90 more stores in the current fiscal year; it’s maintained double-digit, same-store sales growth in recent quarters, notching 16 percent in the three months to September. Franchising will be a key part of the expansion. Kalyan opened its first franchisee-owned, company-operated store in Aurangabad in western India three years ago. Today over half of its stores are franchisee-owned, and Kalyan expects to convert more of its company-owned stores.

“Franchisees help you manage the complexity of the business,” says ICICI’s Menon. “If you do everything on your own you cannot scale up. They also become your funding partners in an industry where it is hard to get credit.” Franchised stores contributed 43 percent to Kalyan’s total revenue in the quarter ended June and the company says it has a long waiting list of potential franchisees.

Also Read: Kalyan Jewellers: How a regional, family business became India's No. 2 jewellery player

Expansion overseas is also part of the plan. The 38 stores it has across the UAE, Kuwait, Qatar and Oman as well as its two stores in the US contributed about 12 percent of total revenue in the most recent quarter. Besides its Iselin, New Jersey, and Chicago outlets, Kalyan plans to add two more stores to its US portfolio this year—targeting the well-to-do Indian diaspora there. Europe is also on the map, with the company launching a store in the UK in October.

Back at home, the company is doubling down on advertising to draw new customers, spending some 13 billion rupees in the past four years. It has a slate of brand ambassadors, such as Bollywood actors Katrina Kaif and Jahnvi Kapoor and regional superstars Nagarjuna Akkineni and Prabhu Ganesan.

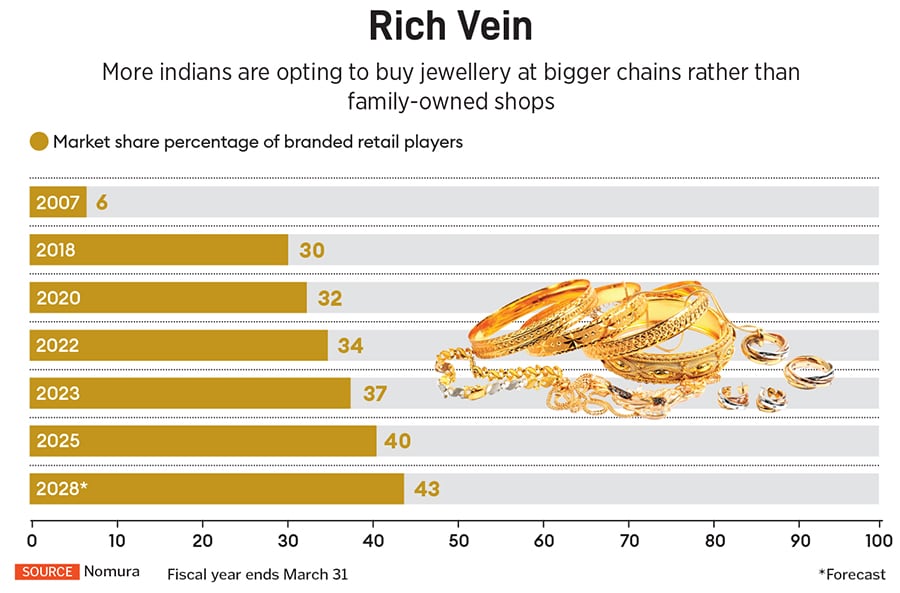

India’s jewellery retail market is a crowded space, ranging from family-owned stores that still draw a loyal clientele to well-established pan-India players such as Tata group firm Titan, which owns jewellery brand Tanishq and is the largest listed jewellery retailer in the country by sales. Then there are regional chains like Pune-based PN Gadgil Jewellers, Kolkata-based Senco Gold and Chennai-based GRT Jewellers, owned by billionaire G Rajendran.

Rivals have also extended their footprints overseas. Tanishq has seven stores in the US and plans to add more in the coming months. Kerala-based chains Joyalukkas, founded by billionaire Joy Alukkas, and Malabar Gold & Diamonds, compete with Kalyan both in India and in the Middle East.

Another key part of Kalyanaraman’s plan to ramp up is Candere, an omnichannel seller of lightweight jewellery. Kalyan acquired an 85 percent stake in the online retailer in 2017 for ₹400 million, picking up the remaining 15 percent last year for ₹420 million. The company opened Candere’s first brick-and-mortar store in Mumbai in 2023, which has mushroomed into a nationwide chain of 96 stores as of September, with more than 50 store openings targeted within the year. Under Kalyan’s ownership, Candere’s sales have jumped ninefold to ₹1.6 billion in fiscal 2025, and the company says it aims to turn in a profit by the end of this fiscal year.

Another key part of Kalyanaraman’s plan to ramp up is Candere, an omnichannel seller of lightweight jewellery. Kalyan acquired an 85 percent stake in the online retailer in 2017 for ₹400 million, picking up the remaining 15 percent last year for ₹420 million. The company opened Candere’s first brick-and-mortar store in Mumbai in 2023, which has mushroomed into a nationwide chain of 96 stores as of September, with more than 50 store openings targeted within the year. Under Kalyan’s ownership, Candere’s sales have jumped ninefold to ₹1.6 billion in fiscal 2025, and the company says it aims to turn in a profit by the end of this fiscal year.

The oldest of seven children, Kalyanaraman grew up in Thrissur, where he earned an undergraduate degree in commerce from Sree Kerala Varma College. But his real education, he says, started in a small textile store owned by his father, TK Seetharama Iyer, where Kalyanaraman worked from age 12 during school holidays. He was stationed at the counter to greet customers and cut lengths from bolts of cloth, and as he got older, he was entrusted with handling the accounts. His reward: A masala dosa at a local restaurant after the shop closed for the day. The most valuable lesson he learned was that the customer is at the center of everything.

His dad set up a textile shop for each of his sons, giving Kalyanaraman his own business to run at 25. Following his example, Kalyanaraman was keen to school his own sons in a similar way and started bringing them to his textile shop when they were children. “We would be so excited to help at the store,” recalls Ramesh. “By the time we went to college, that was all we knew and wanted.”

Kalyanaraman’s store also offered wedding attire and customers would routinely ask if he stocked jewelry too, he explains. Taking the cue, Kalyanaraman pooled ₹2.5 million (then $79,000) of savings with ₹5 million that he borrowed to start his new business in 1993. At the time, jewellery was sold through small shops offering a limited selection. Kalyanaraman decided on a different approach: His first store in his hometown was spacious, covering 370 square meters to accommodate a large variety of jewellery displays.

In the early 2000s, he began offering a Bureau of Indian Standards certificate to authenticate gold purchases. “It was all about building trust,” says Kalyanaraman. “We had to prove to the customer that the gold they were buying was of good quality.” He also installed a karatmeter, which uses x-ray fluorescence to determine gold content and purity, allowing customers to test the gold in the store.

These value additions drew buyers in droves and he took on debt to open two more stores in his home state. From 2004, he began extending the chain’s reach across south India—first in nearby Tamil Nadu and then in the states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. He branched out to launch My Kalyan, a chain of smaller stores in semi-urban and rural locations.

By 2012, he was ready for Kalyan’s nationwide rollout. The first store outside south India was opened in Ahmedabad in western India and the following year he entered Mumbai and simultaneously headed overseas to Dubai with its growing population of Indian expats. In another gamble, in 2012 he roped in Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan as a brand ambassador, unleashing a multimedia bombardment of TV commercials, print ads and billboards.

As Kalyan became a recognised name, a steady stream of investment bankers and private equity executives began showing up in Thrissur. “We didn’t know anything about capital markets,” admits Ramesh. “But we knew we needed outside capital to build the brand and the infrastructure.”

When private equity giant Warburg Pincus approached them with an offer, the family was initially wary, but eventually struck a deal. In 2014, the PE firm paid ₹12 billion (the equivalent of $200 million then) and invested another ₹5 billion three years later. The two tranches gave Warburg a 30 percent stake. (Kalyanaraman first became a billionaire in 2013, based on his company’s rising sales and profits before the Warburg deal.)

“We had identified jewellery as a particularly attractive segment of the Indian consumption story,” says Vikram Chogle, Warburg Pincus’ Mumbai-based managing director. “But there were a whole host of players within that segment. Kalyan was well-reputed, particularly in south India, and a few things stood out—the strength of the brand, its ability to connect with consumers in its home and adjacent markets, and a very long-term orientation of the family.”

Analysts say Warburg helped Kalyan implement corporate governance and financial reporting systems, brought in a layer of professional management and readied the firm to go public. “What we did with Warburg in six to seven years would have taken 15 years if we had tried to do it on our own,” acknowledges Ramesh.

But Kalyan’s debut on the BSE and the National Stock Exchange in 2021, smack in the middle of the pandemic when investor sentiment was weak, drew a tepid response and it listed at a 15 percent discount to its IPO price. Shares have jumped over sixfold since the IPO, though they lost some ground from the January peak of ₹795. The stock took a hit from online rumours that a mutual fund firm allegedly was bribed to increase its holding in the company. Both parties denied the allegations, describing them as “baseless, malicious and defamatory”.

Warburg, which partly cashed out in the IPO reducing its holding to around 26 percent, has since sold that stake saying it “successfully” exited Kalyan in 2024, without disclosing transaction details. The PE firm is reportedly again in talks to take a 10 percent stake in Candere for ₹8 billion. Both Warburg and Kalyan declined to comment.

At Kalyan, overall strategy is guided by Kalyanaraman, while Rajesh manages inventory and technology with Ramesh handling marketing and operations. Rajesh is also involved in procurement of gems and jewellery and spends time overseeing design and new products. “In the past three to four years we’ve really worked on expanding the range,” he says.

Kalyan’s customer focus is as razor sharp as it was from the start. For instance, in the early years, complaints that some earring screws were prone to coming loose after a few wears saw Rajesh working with craftsmen to ensure a tighter fastening. Feedback that certain necklaces had a tendency to get caught on clothing led him to instruct artisans to cover sharp edges with fabric. Anish Saraf, a Warburg Pincus managing director in Mumbai, who negotiated the Kalyan investment, observes that, “the family is very passionate about Kalyan, and all their time and effort is spent on scaling and improving the business.”

Sasikala Sridhar, a longtime customer of a rival jewellery chain, says she switched to Kalyan 18 months ago, won over by the white-glove treatment she received: “The salespersons showed us so many designs.” The 54-year-old has returned to Kalyan nearly 10 times in the past year to shop for her son’s October wedding, spending nearly ₹700,000 on gold bracelets and chains as well as a pair of diamond earrings.

For Kalyanaraman, customers, even picky ones such as Sridhar, remain first. “I talk to a minimum of five to ten customers every day over the phone,” he says, adding that he also regularly visits Kalyan stores across India to meet them personally. “I am happy when I get negative feedback so that I can solve the problem,” he says.

First Published: Dec 29, 2025, 11:59

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 26, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)