Mir Imran: Licence to invent

InCube Labs’ chairman and CEO on his inventions that have saved millions of lives and become industry standards in the US. He reveals the secret to his method and why India isn’t an innovation hub yet

When Mir Imran was five, his mother gave him a licence to kill. Not in the 007 way.

As a child, Imran was curious and dexterous with a screwdriver. He would open up some of the things his family bought: Watch, transistor radio, clock, etc. Instead of screaming at him, his mother started to buy two of each. The boy was free to unravel one but must not touch the other.

Little did the mother know that her unusual tolerance as an Indian parent in Hyderabad of the 1960s would put Imran on the path to becoming an inventor whose success is matched only by his ability to stay out of the limelight. The latter—eluding the limelight—can also be attributed to his laser-sharp focus on coming up with solutions to problems and not really scaling them up as businesses.

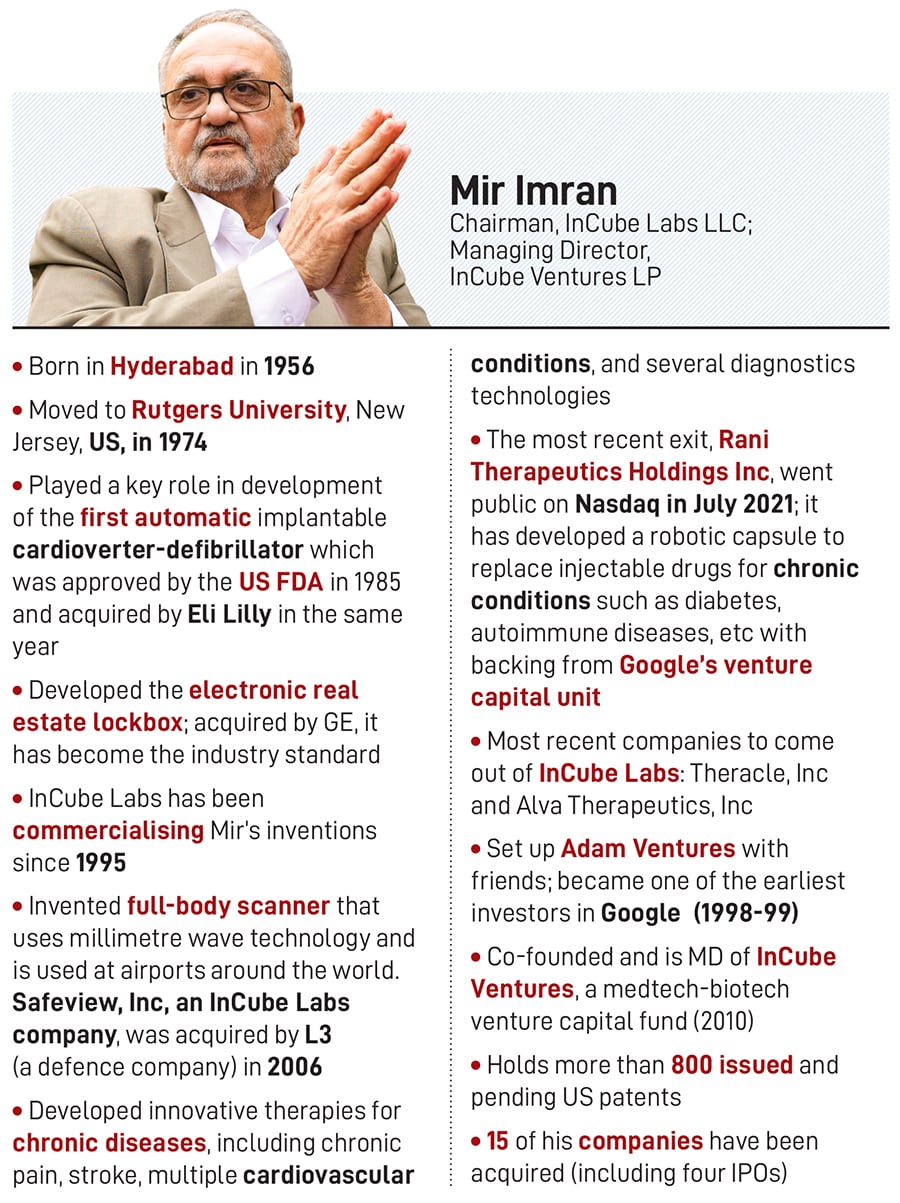

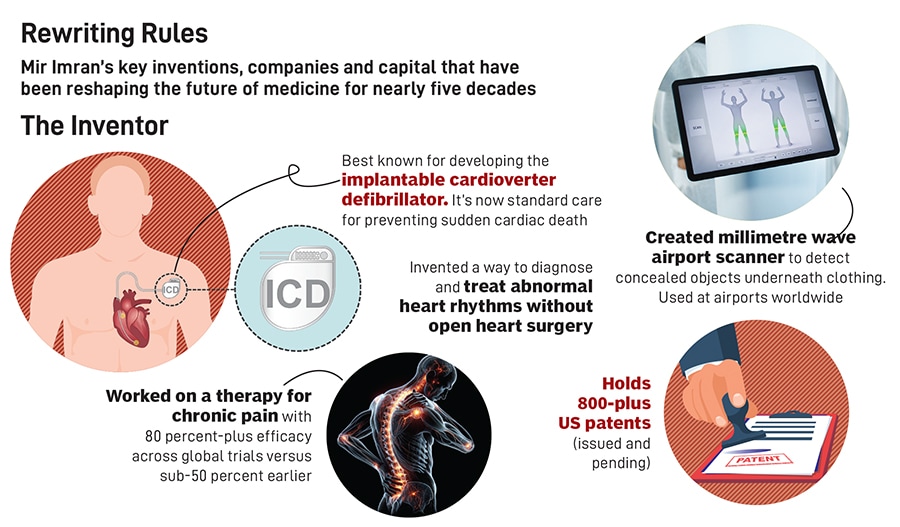

Moving to the US in 1974, Imran went on to become a key figure in the team at Intec Systems that developed the first automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) to be approved by the United States Federal Drug Administration (USFDA).

Automatic ICD is an electronic device that continuously monitors the heart. If the user experiences cardiac arrhythmia, it generates an electric shock to the heart to bring them back to life. It has become a standard in cardiac care and saved millions of lives. Eli Lilly, the global pharma giant now making headlines for its weight-loss drugs, bought Intec Systems, the company that owned the ICD, in 1985. Eventually it went to Boston Scientific in 2004 for $26 billion.

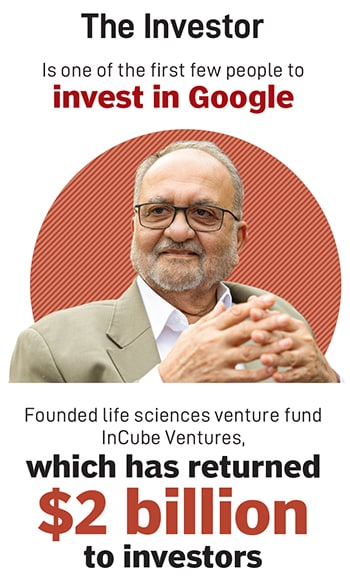

Cardiologist Michel Mirowski, who roped in Imran to work on the ICD, thought it would cost about $100,000 to develop. It ended up costing $27 million and took six years. The experience proved invaluable for Imran not only in inventing but also in raising funds. He would go on to set up Adam Ventures with his friends. It became one of the earliest investors in Google.

Down the road, Imran developed a robotic pill to replace injectable drugs for chronic conditions such as diabetes, with backing from Google’s venture capital unit. To him goes the credit for inventing the full-body scanner at airports that uses millimetre wave technology and is used around the world; and the electronic real estate lockbox, which keeps track of every realtor entering a house that is up for sale (acquired by GE, it has become the industry standard).

In all, Imran has founded more than 20 life sciences companies and two tech firms. Of these, 15 have seen liquidity events, which means they either floated public issues or were acquired. His most recent exit, Rani Therapeutics Holdings Inc, went public on Nasdaq in July 2021.

He has developed innovative therapies for a number of chronic diseases, including anaemia, chronic pain, stroke, diabetes, and several cardiovascular conditions. Rani Therapeutics is revolutionising the management of chronic diseases by replacing painful injectable therapies with oral biologics. He holds more than 800 issued and pending US patents.

Imran is also the co-founder and managing director of InCube Ventures, a medtech-biotech venture capital fund.

So, why isn’t he on the Forbes list of the richest people?

“It depends on what yardstick you use to measure success,” Imran tells Forbes India.

We are sitting on white chairs around a plastic table in the lawns of the Delhi Gymkhana Club. He is sipping on turmeric tea, which he visibly detests and is eyeing our masala tea with milk. “I measure success in the lives I impact. Yes, I get satisfaction, but I’m not chasing fame.”

That is another mystery. For someone with so many accomplishments, why isn’t Imran a household name in the country of his birth?

“I’m sure I could have been much more [famous]. If I wanted to get a lot more exposure, I would have figured it out, right? I figured out so many other crazy things, yes. So that wasn’t, is still not, the driver,” he says.

So what is the driver? Is it solving a problem?

“Solving problems that have a big impact on people,” he says.

Is that his father’s influence? Imran’s father practised medicine in a small village on the border of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra. Imran and his brother lived with their grandmother in Hyderabad. Their mother lived with her husband and made frequent visits to the city. Most of the father’s practice was pro bono.

Imran agrees that he respected his father a lot for the way he thought of his medicine practice as almost a social service. But he also points out that had he conformed to his father’s thinking, his career would have taken a path different from the one it ended up taking.

“I respected him a lot, especially his detachment from money. That definitely shaped me. But if my father had really influenced me, I would have been in Osmania,” he says.

Instead, he went to Rutgers in New Jersey, US, where he obtained a BS in electrical engineering and MS in bioengineering. He also attended the Rutgers Medical School. For that, he had to jump through several hoops.

Also Read: Anti-ageing is a huge area. Everyone is jumping into it: Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

By the time he reached the ninth grade, Imran had decided to go to the US to study engineering. In the Hyderabad of that time, this was unthinkable. No one knew how to, or why. Without telling his parents, Imran started to go to libraries, where he jotted down names of US universities and wrote to them for their big fat brochures. To be able to take the essential SAT test, for which he needed to go to the nearest US consulate, Imran told his family he was going to see his friend’s sick grandmother.

When he started getting accepted at various universities, his father, who eventually agreed to the decision to send him to Rutgers, borrowed the ₹30,000 Imran needed. Imran converted the money into about $4,000—the exchange rate was about ₹7 to a dollar—after paying commissions and boarded a plane.

It was 1974. He had just completed intermediate.

Soon after joining Rutgers, Imran realised his $4,000 was not going to be enough for the four-year course. That was where the US academic system came to his rescue. It required you to take a minimum of 12 credits, but there was no cap on how many you could take. Imran took 30 and finished his four-year undergraduate course in two.

“Engineering came naturally to me. It was a breeze. That’s why I was able to finish early,” he says.

But engineering was not the only thing he studied. He wanted to do projects for the medical school, which was on the same campus, to make some money. The professor at the medical school liked Imran’s work, but said he must enrol, and not just do projects for it. Imran did not really want to, but needed the money. And he could not say no to the professor.

“You know, your professor is God, and whatever they say you can’t fight with them, can’t say no. I had the typical Indian mindset. It was like being drafted into the military,” he says.

While on campus, he tried other ways to make money and also incorporated a company, but was not too successful with it. It was joining the medical school that proved to be a turning point. That was how he met Michel Mirowski, a cardiologist from Johns Hopkins.

Mirowski was born in Warsaw, Poland, and had escaped the holocaust by fleeing to the Soviet-occupied region of Poland when he was 15. He moved to Israel to become a physician. There he met Harry Heller, chief of medicine at Tel HaShomer Hospital, who became his mentor. Heller later began to suffer from ventricular arrhythmias and succumbed to ventricular fibrillation.

Heller’s death made

Mirowski look for ways to miniaturise the external defibrillator and make it completely automatic, so patients could survive outside a hospital. In the 1970s, he happened to speak to Imran’s professors at the medical school and decided to rope him in to build a wearable defibrillator.“I studied cardiology and began to realise why my engineering professor wanted me to go to the medical school. It gave me insight into what at that time even cardiologists did not know, which is, how cardiac arrhythmias behaved. They had only a vague understanding of it,” says Imran.

They decided to make their defibrillator automatically implantable and set up a company to make it. Neither had heard of venture capital (VC). In fact, VC was not much of a thing on the east coast of the US. So, they went to friends, other physicians, and a fund house and founded a tech company in Pittsburgh with a projected budget of $100,000. As mentioned earlier, they ended up spending $27 million.

Imran wanted their own company, Intec Systems, to scale up, but the investors wanted an exit. That is how it was sold to Eli Lilly. By then, Imran had friends in California who asked him what he was doing in Pittsburgh. So, he got into his car, moved to California, and started another defibrillator company. This invited a lawsuit from Eli Lilly, which Imran fought until the legal budget ran out. He set up another company in a different field, and another in yet another different field, and so on. He did not want to give his all to any one company.

“I was launching a new company every year or 18 months, hiring CEOs for the previous companies and just working seven days a week and having a ball. When you are working for a company, you are expected to give all your intellectual property to that one company. I don’t want to do that,” he says.

At times, it did not take much for him to start a company. One such is a jewellery company which he started almost on a whim. It so happened that his neighbour, whom his describes as “a wonderful lady”, had stage four cancer. She was going through a difficult period and one of the things that made her happy was jewellery. Imran suggested she get into the jewellery business. But she was hesitant, because she had a PhD in education and knew nothing about the jewellery business. So, Imran offered to design the stuff for her.

Could he really design jewellery?

“How difficult can it be?” he shoots back.

Well, it can be very difficult.

“I got inputs from what I looked at, what she (the neighbour) liked, and some other women in my life liked. I used that as customer input. I have an aesthetic eye myself,” he says.

What does it take for an India-born to make it big as an inventor outside India, especially in a country such as the US?

“Courage, creativity, hard work and… I think… chasing big problems,” says Imran.

Still, what is his process? How does he invent or innovate? How does his mind work on such diverse projects?

“Most innovators don’t know how they innovate, because they are not paying attention to the process,” says Imran.

In his early 20s, he became enamoured of the whole process of innovation and creativity. He read a bunch of books that did not explain much. He remained curious but realised that he was inventing and innovating naturally. He decided to consciously observe all that was going on in his mind to try and spot a pattern.

It took 10 years of conscious observation to see the pattern.

“The pattern is that I do not care about the technology,” he says. He was inexorably drawn to unsolved problems and would spend time on them until solutions emerged. “I would let the problem tell me how it wanted to be solved,” he says.

That is how he ended up solving several unrelated problems. The innovations were different from one another, each with a different technology. “The common theme was that I was driven by the problem,” he says. He worked with professors at Stanford and helped develop a process for innovation, which has become a pedagogical programme in several universities around the world.

During his decades of innovation and solving problems, did he ever worry that he might one day lose this ability?

“Yeah, I guess if somebody hit me with a hammer or, you know, through brain damage I would lose it,” he says. “But, you know, we all die anyway.”

Imran has dabbled in several other interesting ventures, not all of which might have culminated in liquidity events. He once tried his hand at making artificial organs, including an artificial womb (“a baby making machine”). But it will be a long-term project and, almost 70 now, he wants to utilise his time elsewhere.

Besides, he puns with an impish grin, “The investors did not have the stomach for it.”

He will be happy if someone else took it up. “My inventions are in the public in the form of patents. Once the patents expire, they become public property,” he says.

When Forbes India met Imran, he was in the midst of a week-long sojourn in India meeting some of the top names from India Inc. He wouldn’t tell us the details, but chances are that he is working on something that could prove to be a breakthrough in diabetes care.

“I’m working on projects that require longer views by the investors, and I think, generally, in my experience, family offices have that kind of play. But not all; some family offices value their money a lot more than it is worth,” he says.

Where does he think India stands today as a country of innovators?

“There is a big gap in India. There are a lot of smart people here, but not a lot of risk capital. The capital here has so many strings attached. They want to control the company. That scares away the innovative people. That’s the gap,” he says.

But why has he focussed so much on health care, an area fraught with regulation, where failure rate is high and the time-to-market long?

That takes us back to Imran’s favourite subject of solving problems.

“There is a huge number of unsolved problems in medicine. I realised that problems in medicine were generally stationary, whereas problems in technology were transient and caused by other technologies,” he says.

For instance, he says, the problem of diabetes is about the same it was a decade ago. So, is it indeed a diabetes-related project for which he was in India? He says he could tell us, but on one condition.

“I’ll have to kill you,” he says with the same impish grin.

That sounds odd coming from someone in the business of saving lives. Besides, it will not really solve any problem.

First Published: Dec 12, 2025, 17:09

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Dec 12, 2025 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)