How regional cinema is packing a punch at the box office

Films in various Indian languages are gaining ground with better economics, and crossing linguistic and cultural boundaries with superior content, and pan-India stars

Major tsunamis are yet to arrive and Bollywood is not even aware of it,” says Pan Nalin, the acclaimed Gujarati filmmaker whose Last Film Show (Chhello Show) was selected for the 2023 Academy Awards in the International Feature Film Category. It is a bold statement to make, but it is backed by box office numbers, investment patterns and a shift in audience preferences across India.

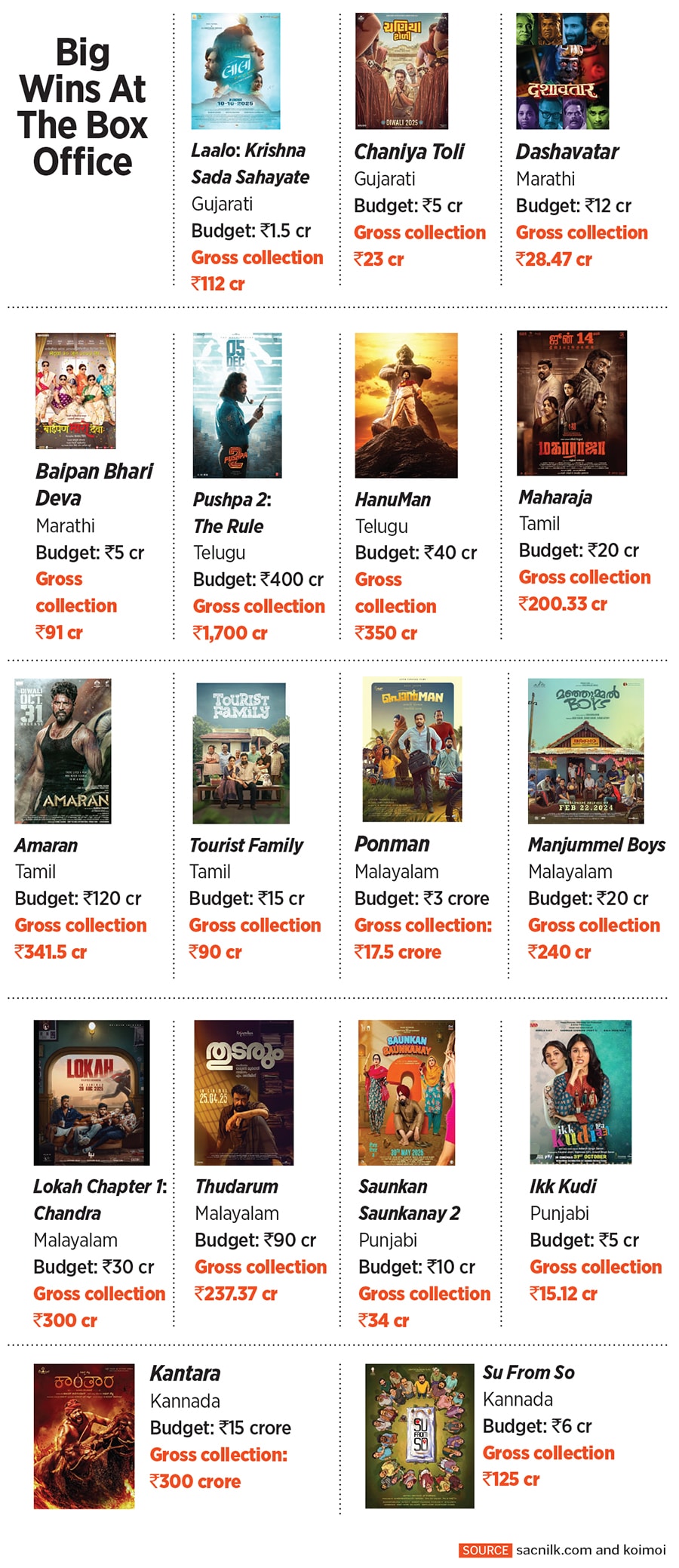

For decades, Hindi films dominated the Indian cinema landscape, while movies in other languages were mostly restricted to their specific regions. The last few years have marked a shift; in 2024-25, Marathi films held their own against Hindi releases in Maharashtra, one Gujarati film—Laalo: Krishna Sada Sahayate—crossed the ₹100-crore mark, and Malayalam film Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra earned nearly ₹300 crore on a budget of ₹30 crore. These instances may signify not just successful runs, but also a restructuring of India’s film economy, where regional cinema is becoming financially viable outside of its home turf.

According to data from PVR Inox, regional cinema’s share in gross box office collections has jumped from 27 percent in FY24 to 31 percent in FY25, as Hindi cinema has maintained its status quo at 55-56 percent, with English-language films dropping from 18 percent to 14 percent due to fewer releases. But the real story lies in the per-film returns, the sustained occupancy rates at cinema halls and the resilience of regional releases compared to big-budget Hindi contenders.

“The shift we’re seeing is not disruptive; it’s more a reflection of how diverse, modern and inclusive India’s cinematic appetite has become. The content pipeline is also diverse and strong,” says Aamer Bijli, film marketing lead specialist at PVR Inox. Regional films are gaining from larger auditoriums, better infrastructure and an audience with an “unparalleled appetite to watch films”, says Bijli. Perhaps that is why 40 to 45 percent of PVR’s new screen additions are planned in the South; currently, 33 percent of PVR Inox’s screens are in southern India, compared to 38 percent in the north.

Investment is flowing towards regional cinema as well, although Bijli says Bollywood is seeing some consolidation and fresh investments through mergers and new backers. As a spokesperson for Sacnilk.com, a widely used Indian platform that tracks box office and entertainment data, says: “These years do not signal the decline of Bollywood; rather, they mark the successful decentralisation of cinematic power. Bollywood remains the most consistent producer by volume, and still holds a substantial market presence. However, it now shares the national stage with multiple powerful centres.”

Regional cinema is being powered by lower financial risks, higher returns and audiences which are hungry for authenticity. Parth Madhukrushna, a Gujarati filmmaker and actor, explains the maths: “A quality Gujarati film can be made for ₹1.5-2 crore and, if successful, can earn between ₹5 crore and ₹15 crore. At worst, Gujarat’s subsidy system, which offers up to ₹75 lakh based on a grading slab, serves as a safety net.” Madhukrushna adds, “With ₹15 crore in hand, I can make around seven Gujarati films. In Bollywood, it won’t even get you one mid-sized film.”

The cost differences run deep. Fees for established Bollywood actors start from ₹5 crore, whereas A-list actors in many regional industries charge a fraction of that. In addition to this, the Hindi film ecosystem has many middlemen, agents and coordinators, each adding layers of commissions and inflating production costs, while regional cinema maintains direct access to talent.

“Stars command 50 to 70 percent of a Hindi film’s budget, leaving little for content. Regional cinema focuses on content, while keeping budgets modest, thereby creating sleeper hits, such as Laalo, which did better than what its producers expected,” says Taran Adarsh, film critic and trade analyst.

“Tighter budgets, strong fandoms and powerful word-of-mouth promotion help regional films deliver consistently higher occupancies, and eventually higher returns,” says PVR’s Bijli. Consequently, while big banner movies see footfalls drop week over week, regional films often keep growing, with some even pulling off houseful shows on weekdays.

“The return on investment is around 8 to 9 percent in Hindi films, while Gujarati films or other regional films average 12 to 15 percent,” Madhukrushna adds. Chaniya Toli, made for ₹5-7 crore, fetched ₹21 crore, while Laalo, made for just ₹1.5 crore, fetched ₹119 crore worldwide.

Marathi cinema is not different. For example, Dashavatar, with ₹28.47 crore in gross collection, returned more than 220 percent on a modest investment of ₹12 crore. Its director Subodh Khanolkar thinks films in local languages are generally made on smaller budgets, and there’s “always an effort to create better cinema with limited resources. That is why, from a commercial standpoint, they often become more viable options”. Dashavtar also becomes first Marathi film to enter the Oscar Contention List for the Academy Awards 2026.

In 2025, many Gujarati films earned more than ₹15 crore, a figure that was unbelievable even two years ago. These include films like Laalo, Chaniya Toli, Vash Level 2, Chandlo and Karkhanu. “These films have delivered strong content. The audience is choosing films based on their content, not on star value,” Madhukrushna explains.

Marathi cinema, too, succeeded on the back of content that appealed to different demographic segments: Naach Ga Ghuma was a comedy about finding a good domestic help; Jarann was a psychological thriller; Fussclass Dabhade dealt with sexual intimacy among married couples; April May 99 was a nostalgic story set in the Konkan region; and the most successful Marathi movie, Baipan Bhari Deva, which earned about ₹91 crore against a budget of ₹5 crore, was about the struggles of middle-aged women; Chandramukhi and Phullwanti were screen adaptations of Marathi literary works. All these films delivered returns of at least 200 percent on their original budgets.

Strong storytelling in small and mid-budget films has proven to get consistent returns. In Telugu cinema, films like Hanuman, which had an estimated budget of ₹40 crore and made upwards of ₹300 crore, yielded returns of over 600 percent in addition to franchises like Pushpa. Other profitable films included HIT: The Third Case, Mirai, Kuberaa, and Court: State vs A Nobody with returns between 50 percent and 300 percent. With culturally specific stories, Tamil cinema also kept up this momentum. Maharaja made over ₹100 crore worldwide on a budget of less than ₹20 crore, yielding returns of more than 400 percent, while Tourist Family made about ₹90 crore on a ₹16 crore budget.

Malayalam cinema emerged as the most profitable with films like Ponman earning ₹17.5 crore on a budget of ₹3 crore, Premalu earning ₹136 crore against ₹10 crore, and Manjummel Boys turning ₹20 crore into more than ₹240 crore in collection. Kannada cinema maintained its post-KGF momentum, with Kantara, which made over ₹300 crore on a budget of ₹15-16 crore and returned nearly 2,000 percent These profits allowed for a larger investment in Kantara: Chapter 1. Mithya, Su from So, and Mahavatar Narsimha also produced healthy theatrical returns on modest budgets.

According to Nalin, “Mumbai studios make films like business shows. Business decisions are made by people in Bandra West, about people in Bandra West and for people in Bandra West. They do not even know what audiences in Bhayandar or Bhopal or Bhatinda want.”

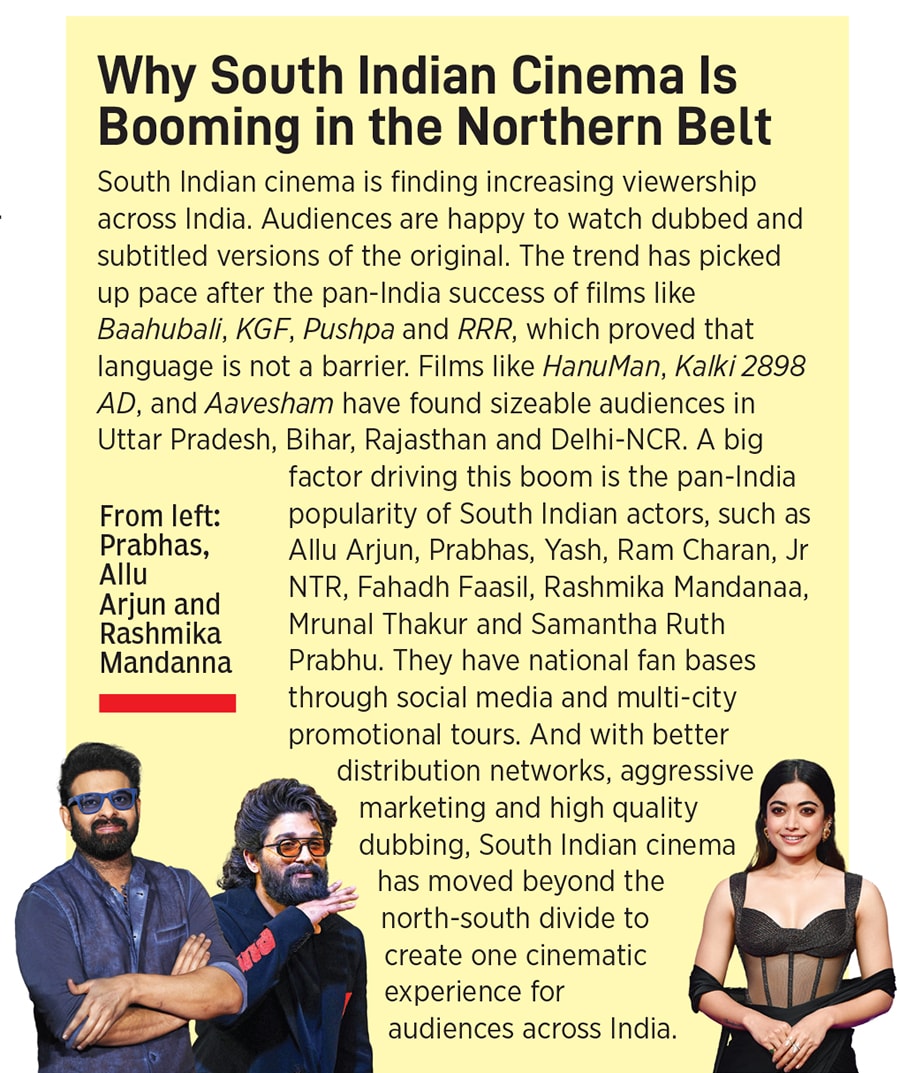

During the Covid-19 pandemic, when theatres closed and audiences turned to YouTube and OTT platforms, they discovered content from other regions, especially southern India, through dubbed and subtitled versions. They found scale, emotional depth, cultural authenticity and, most importantly, entertainment; all elements that had gradually disappeared from mainstream Hindi releases. As Adarsh points out: “Audiences realised the sheer scale of entertainment available. That triggered a huge shift in viewing behaviour.” These films told stories vastly different from Bollywood’s increasingly jaded scripts.

Khanolkar explains what worked for Dashavatar was its setting in the Konkan region, its traditions, folk theatre and commentary on local issues. “Audiences felt what they were seeing on screen wasn’t the story of some distant stranger… it belonged to someone among them,” he says. As Tamil screenwriter Ashameera Aiyappan puts it, “The stories that have reached the pan-Indian audience have done so because they were authentic to their geography, while having universal themes, arcs and emotions.” Kantara being a case in point. Jeo Baby, director of the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen, has an even simpler explanation: “I tell stories about human conditions. These are not different everywhere in the world.”

Nalin says the Hindi film industry has “completely forgotten how to tell stories, and has become a packaging industry”. In contrast, he says, regional cinema is filling the vacuum with rooted stories of real people with real problems and genuine emotional connections, “not formulaic films filled with titillating dialogues and songs, gratuitous violence, ridiculous actions and soul-less one-dimensional characters. This cringe fest is destined to collapse”.

Adarsh says Hindi films of the 1970s and 80s were rooted in entertainment, and catered to all audience segments. But from the mid-1990s and the 2000s, they became metro-centric, catering only to multiplex audiences. “What about the rest of India?” he asks.

Bijli says India is undergoing a “a new fandom culture”, where cultural assimilation and social media have flattened boundaries and pan-India fandoms are forming around films and actors, compared to the earlier region-specific ones. “We’ve moved from siloed, regional loyalists to a collaborative national cinematic culture where language is no longer a barrier,” he says.

Regional cinema’s strength has long come from its inter-regional collaborations, a South Indian legacy that other industries are only now adopting. As Aiyyapan, also a former film journalist, says, “That’s something that has always been part of the cinema fabric here.” She recalls how Madras (now Chennai) once served as the hub of multiple film industries, before they shifted to Kochi or Hyderabad. “It has been quite common for stars such as Kamal Haasan, Sridevi, Nagarjuna and Mammootty cross over and do films in other languages, or remake stories from other languages,” she says. What we are seeing today, she adds, is simply a continuation of that same dynamic.

The ecosystem is changing in terms of star value too. Hindi’s cinema’s biggest names are still Shah Rukh Khan and Salman Khan, but the pool of A-listers in South Indian cinema has grown exponentially with the likes of Prabhas, Allu Arjun, Ram Charan, Jr NTR, Dhanush, Fahadh Faasil, Mahesh Babu and Prithviraj. Adarsh says, “When Allu Arjun says his lines in Pushpa, the whistles will resound from the North, East, Gujarat and Maharashtra. That universal connect shows how regional stars are fast turning into national icons.”

Nalin, who has consciously chosen languages like painters choose colours—his first short was in Manipuri, his first feature film in a Ladakhi dialect and the latest, Last Film Show, in Gujarati—believes in local stories going global. His film Samsara (in Tibetan) was acquired by Miramax and grossed ₹130 crore worldwide in 2003. “In India, we have never been given credit for selling a Gujarati film to 65 countries, or running a Gujarati film in Japanese theatres for 34 weeks,” he says, with some frustration.

Changes at the structural level are no less significant. Young filmmakers are looking at cinema as an entrepreneurial venture, bringing in fresh thinking and risk-taking. New technologies are being adopted, and knowledge of marketing and promotions is increasing. Corporates have started taking regional film industries more seriously. And since audiences now consume content from across the globe, their expectations have gone up, forcing filmmakers to consistently produce quality content.

As PwC’s annual entertainment and media report 2025 notes: “Bollywood has traditionally dominated the Indian box office, but in recent years, southern films—particularly those in Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam—have gained significant momentum. These regional cinemas are consistently delivering top-grossing releases, often outperforming mainstream Bollywood films in terms of box office collections.”

Adarsh believes this shift is permanent. “It’s absolutely here to stay,” he says. Baahubali changed the game, and now directors like Rajamouli, Rishabh Shetty, Lokesh Kanagaraj, and stars like Ram Charan, Jr NTR, and Allu Arjun are no longer local heroes, but pan-India faces. The real hero though, as Palin reiterates, is content; star power can attract crowds for one weekend, but only word-of-mouth sustains a film.

Baby thinks structural freedom is one of the reasons for his industry’s success: “There was a time where directors could express their ideas. Many directors also became producers. That increased the freedom to present the idea many times over.” Added to this is an audience that is asking for and accepting quality films, thus creating an ecosystem where content can flourish.

“Success is now determined by the ability of a film to transcend linguistic barriers and deliver an unmissable theatrical experience. The future is a multi-polar, highly competitive, and excitingly dynamic landscape,” adds the Sacnilk spokesperson.

Of course, challenges remain. Nalin says beyond the momentum, investors still want “packaged” entertainment and the same top 10 stars. Many regional films are still financed by filmmakers themselves, and it would remain a big challenge to break this “vicious cycle of marketing and distribution” as cinema halls and multiplexes are owned by corporates in Mumbai and Delhi. Khanolkar agrees that fully stable financing still eludes Marathi films, where assured profits are not guaranteed through OTT platforms, satellite rights or distribution networks.

Yet the industry remains optimistic. Khanolkar sees a future where diverse voices strengthen the national cinema ecosystem. “The diversity of India’s languages, regions, cultures, and stories is what makes the country richer and more vibrant. Audiences are now responding not only to films in their own language but also to those made in other regional languages, and that will have a positive impact on our national film industry. Our local stories are now reaching audiences across the country and even internationally, and that is something to be proud of,” he says.

For investors, producers and filmmakers, regional cinema is at once a cultural renaissance and a commercial opportunity. With lower entry barriers, rooted storytelling, passionate audiences and proven returns, India’s regional industries are not just challenging Bollywood’s dominance, they’re also redefining what Indian cinema can be. The revolution has begun, and it speaks in many languages.

First Published: Jan 05, 2026, 16:59

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Jan 09, 2026 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)