Did you hear the one about a top Trump administration official praising Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the liberal firebrand from the Bronx?

You may be waiting for a punch line. But this is not a joke.

Lawrence Kudlow, director of President Donald Trump’s National Economic Council, singled out Ocasio-Cortez for praise recently — an unusual and illuminating example of people on the right and the left ganging up on an established tenet of the mainstream middle.

What led to this meeting of the minds is a concept called the “Phillips curve.” The economist George Akerlof, a Nobel laureate and the husband of the former Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen, once called the Phillips curve “probably the single most important macroeconomic relationship.” So it is worth recalling what the Phillips curve is, why it plays a central role in mainstream economics and why it has so many critics.

The story begins in 1958, when economist A.W. Phillips published an article reporting an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation in Britain. He reasoned that when unemployment is high, workers are easy to find, so employers hardly raise wages, if they do so at all.

But when unemployment is low, employers have trouble attracting workers, so they raise wages faster. Inflation in wages soon turns into inflation in the prices of goods and services.

A couple of years later, Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow — who also both went on to win the Nobel in economics — found a similar correlation between unemployment and inflation in the United States. They dubbed the relationship the “Phillips curve.”

After its discovery, the Phillips curve could have become just a curious empirical regularity. But Samuelson and Solow suggested it was much more than that. In the years that followed, the Phillips curve came to play an important role in both macroeconomic theory and discussions of monetary policy.

For centuries, economists have understood that inflation is ultimately a monetary phenomenon. They noticed that when the world’s economies operated under a gold standard, gold discoveries resulted in higher prices for goods and services. And when central banks in economies with fiat money created large quantities — Germany in the interwar period, Zimbabwe in 2008, or Venezuela recently — the result was hyperinflation.

But economists also noticed that monetary conditions affect economic activity. Gold discoveries often lead to booming economies, and central banks easing monetary policy usually stimulate production and employment, at least for a while.

The Phillips curve helps explain how inflation and economic activity are related. At every moment, central bankers face a trade-off. They can stimulate production and employment at the cost of higher inflation. Or they can fight inflation at the cost of slower economic growth.

Soon after the Phillips curve entered the debate, economists started to realize that this trade-off was not stable. In 1968, Milton Friedman, the economist and author, suggested that expectations of inflation could shift the Phillips curve. Once people became accustomed to high inflation, wages and prices would keep rising, even without low unemployment. Soon after Friedman hypothesized a shifting Phillips curve, his prediction came to pass, as spending on the Vietnam War stoked inflationary pressures.

In the mid-1970s, the Phillips curve shifted again, this time in response to large increases in world oil prices engineered by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries — an example of a “supply shock” in economists’ parlance.

Today, most economists believe there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment in the sense that actions taken by a central bank push these variables in opposite directions. As a corollary, they also believe there must be a minimum level of unemployment that the economy can sustain without inflation rising too high. But for various reasons, that level fluctuates and is difficult to determine.

Enter Ocasio-Cortez. While questioning Jerome Powell, the Fed chair, during a congressional hearing in July, she suggested that the central bank’s understanding of inflation and unemployment was flawed.

“Do you think it is possible that the Fed’s estimates of the lowest sustainable estimates for the unemployment rate may have been too high?” Ocasio-Cortez asked.

“Absolutely,” Powell replied. The sustainable unemployment rate now appears to be “substantially lower than we thought.”

The next day, Kudlow applauded the congresswoman’s questioning. “Ms. AOC kind of nailed that,” he said.

The motives of these unlikely allies are easy to surmise. Ocasio-Cortez is presumably more concerned about unemployment than about inflation. Kudlow, who serves a president running for reelection, is undoubtedly praying for a strong economy. Both interests would be served by dovish monetary policy.

To some extent, Ocasio-Cortez and Kudlow are both right. The unemployment rate, now at 3.7%, is lower than the level most economists thought was possible without igniting inflation. This period is providing yet more evidence — though we didn’t really need it — that the Phillips curve is unstable and, therefore, an imperfect guide for policy.

But unstable does not mean nonexistent, and imperfect does not mean useless. As long as the tools of monetary policy influence both inflation and unemployment, monetary policymakers must be cognizant of the trade-off.

Powell was smart to acknowledge during his congressional hearing that the Fed’s track record is flawed. But the uncertainty inherent in monetary policymaking does not mean that “the single most important macroeconomic relationship” can now be ignored.

The Fed’s job is to balance the competing risks of rising unemployment and rising inflation. Striking just the right balance is never easy. The first step, however, is to recognize that the Phillips curve is always out there lurking.

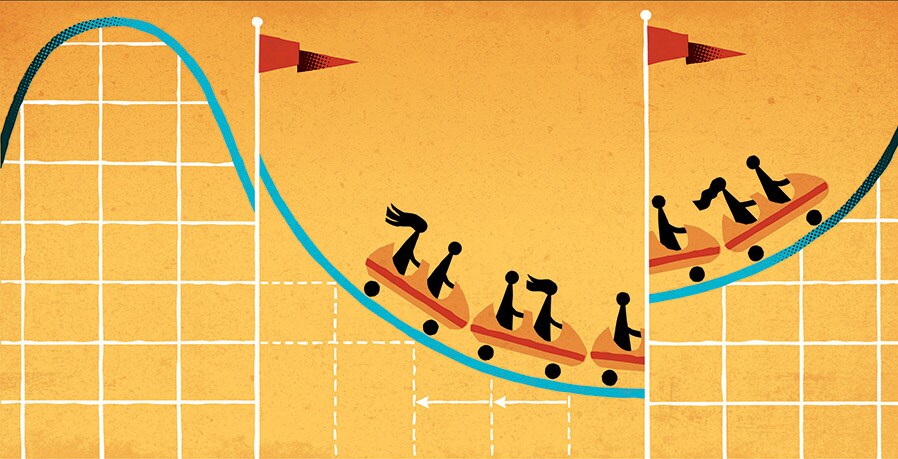

With unemployment and inflation now low, it might seem that their relationship no longer matters. Not so fast, says the economist N. Gregory Mankiw. (Tim Cook/The New York Times)[br](Economic View)

With unemployment and inflation now low, it might seem that their relationship no longer matters. Not so fast, says the economist N. Gregory Mankiw. (Tim Cook/The New York Times)[br](Economic View)